Martin Luther King Jr. forgot Coretta’s birthday in 1965, but she said she didn’t mind.

“In the light of my own involvement and commitments,” she said, “it is not too difficult for me to understand and forgive little things like this which do occur, sometimes.”

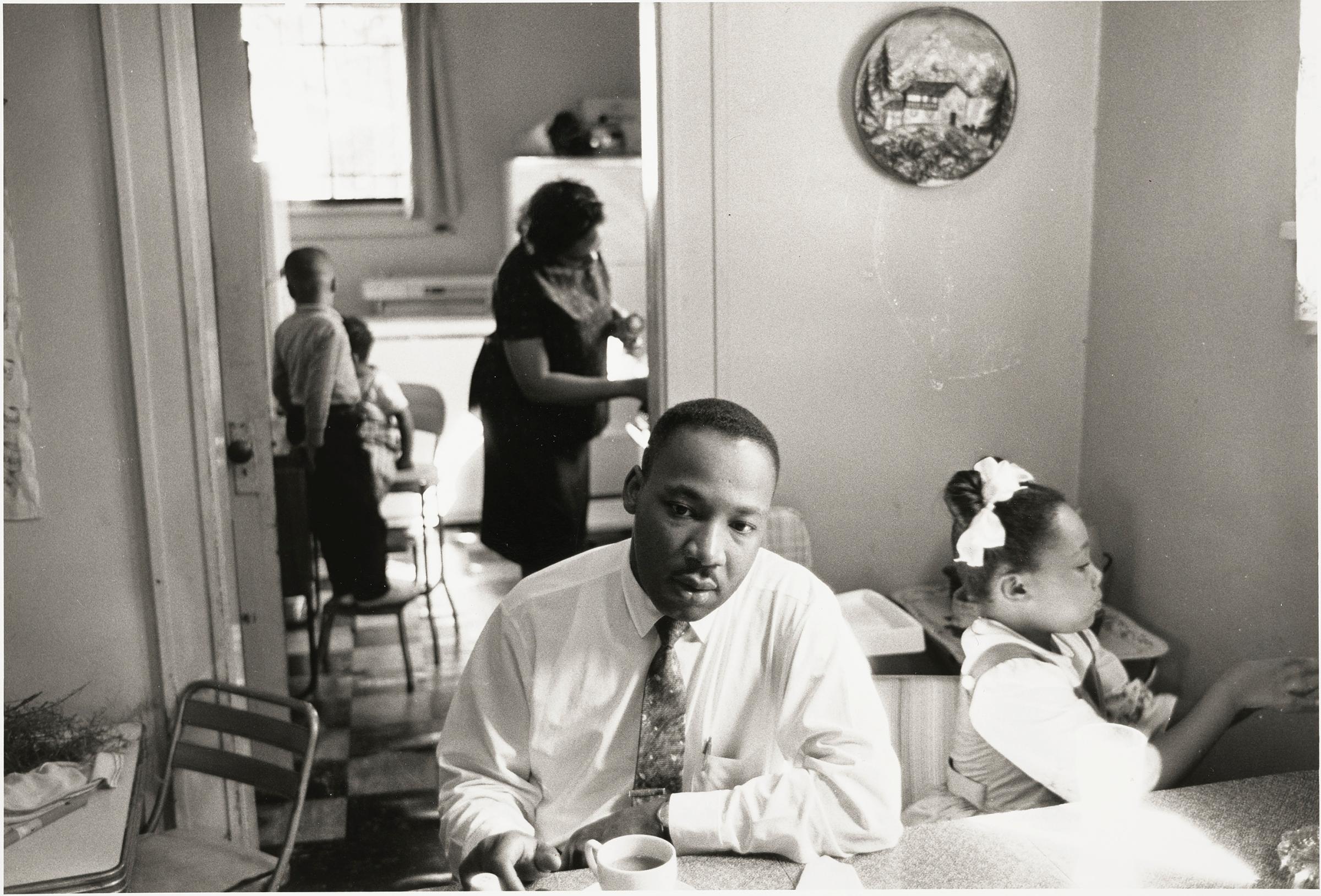

Coretta Scott King was thirty-eight years old, the mother of four children, ages two, four, seven, and nine. In 1965, she spent more time than ever out of the house, working for the movement, beginning in March with a series of Freedom Concerts on the West Coast. In April, she traveled to Detroit for a dinner honoring and raising money for Rosa Parks, who had struggled to find work, first in Montgomery and later in Detroit, and who had suffered deteriorating health.

In May, Coretta King spoke at a gathering of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom in Chicago. And on June 8, she was the only woman to speak at an anti–Vietnam War rally attended by more than fifteen thousand people at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

Earlier that year, at an SCLC retreat, Martin had asked Coretta to speak about Vietnam and whether the organization had a responsibility to take a stand against the war. “I talked about how it would continue to drain resources from education, housing, health, and other badly needed social programs,” she recalled. “I said, ‘Why do you think we got the Nobel Prize? It was not just for civil rights . . . Peace and justice are indivisible.’ ”

It was Coretta’s passion for activism that had first attracted Martin, back in 1952, when she had been enrolled at the New England Conservatory of Music and he had been pursuing his doctorate at Boston University. On their first date, they had discussed the merits of capitalism versus communism. He explained that he intended to devote himself to the fight for racial justice. Coretta, having attended the progressive and integrated Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, thought she would have the edge on this well-bred young man when it came to passion for social reform. She was pleasantly surprised to find that he seemed determined to fight racial discrimination, even if he was not yet sure how to do it.

King was attracted to Coretta in no small part because her experience as an activist exceeded his own. Thirteen years later, however, she expressed frustration with her limited role in the civil rights movement.

“My husband feels it important that one parent remain at home to give them [the children] security,” she told a reporter in Seattle. “But I would like to make a more complete witness by marching, and, if necessary, going to jail.”

Martin, on the other hand, almost never spent time home alone with the children when Coretta traveled. Instead, the Kings relied on friends and family to watch Yolanda, Martin, Dexter, and Bernice. In a memoir written years later, Coretta recalled a conversation in which she told Martin she wanted to take a more active role in the movement:

During one exchange, he told me, “You see, I am called [by God], and you aren’t.”

I responded, “I have always felt that I have a call on my life, too. “I’ve been called by God, too, to do something [. . .]”

Still not convinced, Martin turned to me and said, “Well, somebody has to take care of the kids.”

“No problem,” I said. “I will do that.”

Looking a bit crushed, he asked, “You aren’t totally happy being my wife and the mother of my children, are you?”

“I love being your wife and the mother of your children,” I said. “But if that’s all I am to do, I’ll go crazy.”

During a 1965 television interview conducted at his home, King was asked if he had educated his wife on matters of activism. “Well, it may have been the other way around,” he said. “I think at many points she educated me. When I met her, she was very concerned about all the things we are trying to do now. . . I wish I could say to satisfy my masculine ego that I led her down this path, but I must say we went down together, because she was as actively involved when we met as she is now.”

The Feminine Mystique, written by Betty Friedan, had been published in 1963 and remained enormously popular in 1965, describing the widespread dissatisfaction among American women, and encouraging them to declare: “I want something more than my husband and my children and my home.” At one point in 1965, Coretta began working on an essay for the first issue of a magazine called New Lady, a publication that billed itself as “the Negro woman’s guide to a new way of life.” By the time she finished, the article ran to thirteen pages of text and photos. Coretta must have been proud of it because she mailed a copy to Rosa Parks. “Women have been the backbone of the whole civil rights movement,” Coretta wrote in the article. “Women have . . . made it possible for the movement to be a mass movement.” It was a simple fact, but nevertheless an overlooked one.

In Montgomery, Parks had sparked the bus boycott and Jo Ann Robinson and the Women’s Political Council had launched it. Aurelia Browder, Claudette Colvin, Susie McDonald, and Mary Louise Smith had served as plaintiffs in the federal lawsuit that led to the Supreme Court decision that desegregated the city’s buses. Ella Baker had long served as one of the movement’s best organizers. Diane Nash had helped initiate the Freedom Rides and cofounded SNCC. Septima Clark and Fannie Lou Hamer had led the push for voter registration in much of the Deep South. And then there were countless women such as Coretta Scott King and Juanita Abernathy who endured many of the same perils as their husbands while receiving little credit for their work, work that included not only marching and organizing but also taking care of children, filling in for their husbands, and advising their spouses on matters of strategy, leadership, and politics. In addition to the other challenges, Coretta Scott King ran her household on a modest budget, because her husband insisted that most of the income from his speeches and writings go to the SCLC.

In her article for New Lady, Coretta offered her clearest explanation of how she navigated a path that left many ambitious women of the 1960s feeling lost and angry. Over and over, she returned to the themes of compromise and perseverance. She began: “While my husband was being prepared for the job that he is doing, I feel that I was being prepared also to be the helpmate… I feel very strongly that it was meant to be this way.”

At Antioch College, as she recalled in the article, she had insisted on doing her student teaching in the Yellow Springs Public Schools, along with her white classmates. But the Yellow Springs schools were segregated, and Antioch officials wanted her to travel nine miles to an integrated school in Xenia, Ohio. She “felt like crying” when her teachers and classmates refused to support her. “Then I thought, ‘I am a Negro and I am going to be a Negro the rest of my life. I just can’t let this kind of thing get me down . . . I’ll have to accept this.’ . . . So I made the compromise,” she wrote.

She accepted even worse, according to Hosea Williams, who said that he witnessed King’s cruel treatment of Coretta on more than one occasion. “ ‘Shut up and go ahead in the back room!’ ” Williams said he heard Martin yell at Coretta. “She would get up quietly and go on back. Martin had told her many times.”

Williams was a frequent critic of Coretta, but if the men in the SCLC dismissed King’s wife, the women admired her. They saw a woman fighting to balance her dedication to her family and her causes. Xernona Clayton, an SCLC staff member from Atlanta who traveled at times with Coretta, said she was always impressed by Coretta’s calm determination. For Coretta to leave Atlanta and perform a concert, she not only had to rehearse, arrange her travel, and promote her appearances but also had to make sure the children would be cared for in her absence. Before leaving, she would type a list of meals for the week, including desserts. Even when she was on the road, without consulting notes or a calendar, Coretta knew when the children had doctors’ appointments, piano lessons, and haircuts, Clayton said, and Coretta checked in frequently to make sure nothing was forgotten.

“Coretta Scott King was a disciplinarian,” wrote her son Dexter, “took no guff from hers or any others. Froze you with a look.”

Carole Hoover, another SCLC staff member, said it was clear that Dr. King respected and relied on his wife’s opinion when it came to high-level questions of strategy. “She was very much engaged with those things that were important to him,” Hoover said. “He genuinely valued her thinking.” People in the office heard rumors about King’s infidelity, and specifically about his relationship with Dorothy Cotton. “That rumor floated several times,” Hoover said. “I don’t think Coretta ever bought into that.”

But others in the SCLC did buy into it. When King returned to Atlanta from one of his frequent trips, he usually went to Cotton’s home before going to his own house, said Stoney Cooks, an SCLC staff member. It was understood within the organization that the relationship had been going on for years. “Only the people who were very close to him even knew about it,” Cooks said, and Cotton “didn’t flaunt it.”

Nevertheless, the women of the SCLC saw Coretta and Dr. King as powerful partners, said Edwina Smith Moss. “They didn’t profess to be perfect, and Coretta was such an asset to Dr. King,” Moss recalled. “She was strong, and she came out of the South . . . If Dr. King ever wanted to quit, she wouldn’t have let him. She was not fearful. If she had been, it would’ve shown . . . She understood the FBI wanted to break them up . . . Coretta had steel. Coretta had a sense of the movement. You couldn’t have done that without a real sense of the movement. She was the power behind the throne . . . She was not the person to break. If she was going to have a battle, it was going to be with Dr. King, and it was not going to be in public . . .”

“It is a great temptation,” Coretta wrote, “to demand more of my husband’s attention. We women are like that. But I have had to realize that he belongs to the world and therefore cannot be the same kind of husband and father that he would like to be.” Doing her part for the cause of freedom, she said, included explaining to the children why their father went to jail and why he wasn’t home as much as other fathers and why, sometimes, he didn’t come home when the family expected him. “I have considered my own role very important from the beginning,” she wrote.

The assassination of President Kennedy frightened her, Coretta wrote. The assassination of Malcolm X frightened her more. She felt stuck, “weak and depressed,” after Malcolm’s death. She reminded herself, she wrote, that she and her husband and all humans were coworkers with God, building a world of peace and love. As she concluded in her article: “When you decide to give yourself to a great cause, you must arrive at the point where no sacrifice is too great. This is the first demand that is made of us in our great struggle for civil rights. I shall stand with Martin Luther King, Jr., my husband, as he faces them.”

Throughout the spring and summer, King hustled from speech to speech, interview to interview, city to city, protest to protest, until August 6, 1965, when he arrived in Washington, D.C., to meet with President Johnson and witness Johnson’s signature of the Voting Rights Act. Joining King were Roy Wilkins, James Farmer, and Rosa Parks, among others. Coretta King watched the ceremony on television. She was home taking care of Marty and Dexter, who had both had their tonsils removed. Martin had been so busy that Coretta had never found time to tell him about the scheduled surgeries. It was one of the few occasions, she wrote years later, when she felt sorry for herself.

“I felt very supportive of his being there,” she wrote, “but I also had this feeling of being alone, of being entirely by myself.”

Later that day, outside the White House, five hundred people protested U.S. policies in Vietnam. King made no public comment on the anti-war demonstration. His focus was on the historic new law, which, he said, would “go a long way toward removing all the obstacles to the right to vote.”

It was, he told reporters, as he prepared to fly home to Atlanta, “a shining moment.”

Adapted from Eig’s biography King: A Life published by Farrar Straus & Giroux

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com