From a shelter on the Southern bank of the Rio Grande in Mexico, Diego tries and fails repeatedly to secure an asylum appointment in the U.S. through a government smartphone app. Diego, 34, has been in Mexico for more than three months after traveling north from Venezuela, but he’s heard of new arrivals suddenly receiving an appointment. “With the new system, I had hoped that those of us who have been here three, four months would be able to get appointments first, that there would be some kind of order,” he says. “But it’s luck, it’s like a lottery.”

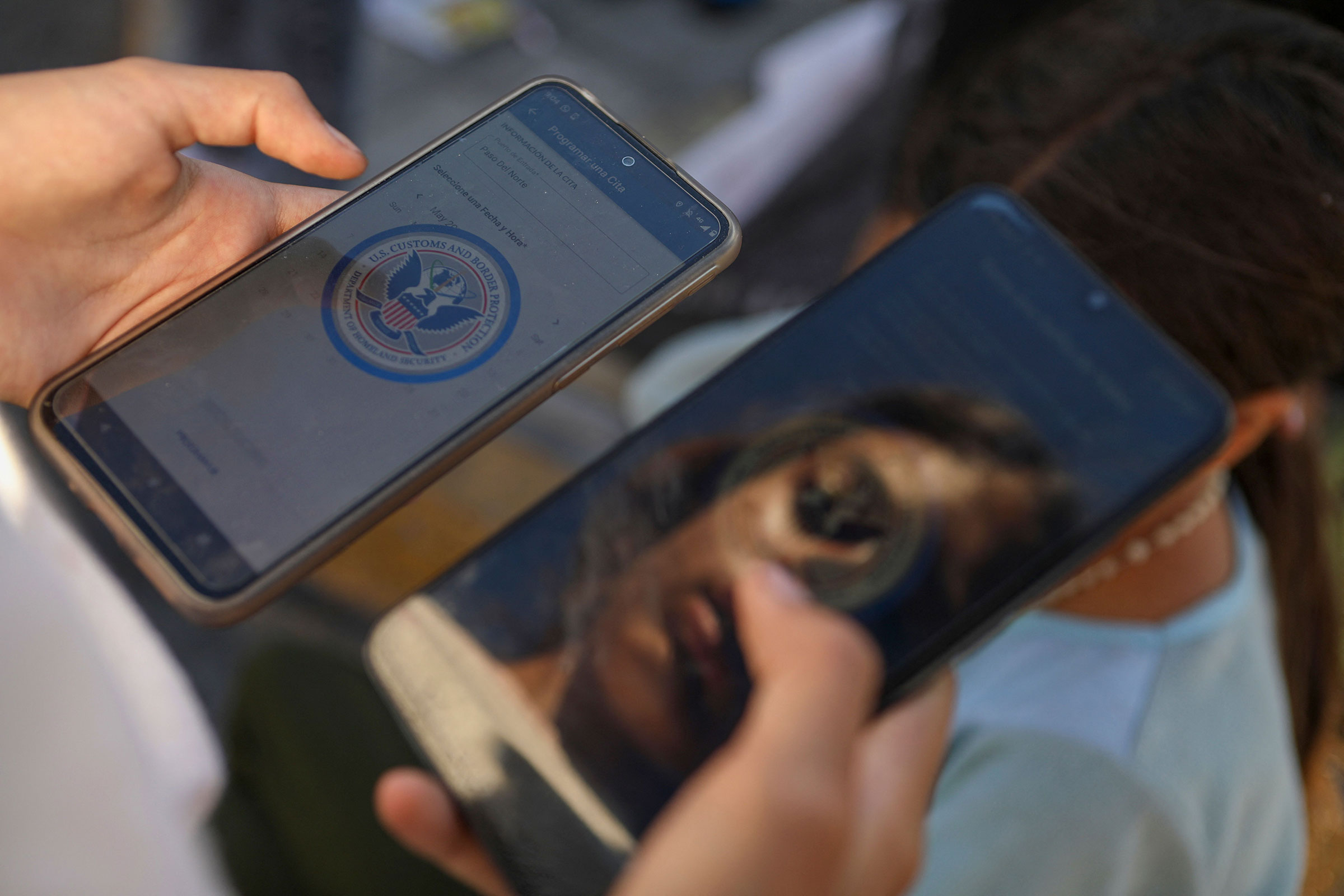

Federal officials have directed migrants seeking asylum in the U.S. to use the CBP One smartphone app to enter lawfully. Under the Biden Administration’s new asylum rules put in place after the expiration of Title 42, if a person did not seek asylum in the country they moved through to get to the U.S. or didn’t use the CBP One app, any asylum claim they make in the U.S. will likely be rejected. But only 1,000 slots are available through the app every day; there aren’t enough appointments to meet the demand. CBP said in a May 5 statement that it will prioritize appointments for those who had been waiting the longest by giving a percentage of appointments each day to the people who registered earliest with the app. (Diego’s legal advocates asked TIME to withhold his last name over concerns that his comments could impact his asylum case.)

Beyond the limited availability of appointments, migrants and immigration advocates have reported issues with how the app works. Among the complaints: error messages keep popping up—often in English. Some migrants may be illiterate or not speak English, Spanish, or Haitian Creole—languages the app uses. Some don’t have an email address. Some nonprofits that work with migrants previously alleged that the app can fail to register those with darker skin tones. The internet connection may not be strong enough for facial capture software. That’s especially true for migrants who live in refugee camps by the river, says Pastor Abraham Barberi, an independent missionary who lives in Brownsville, Texas and frequents Matamaros, Mexico across the border. Migrants may not have a smartphone or if they do, they may not have the technological savvy or enough memory to use the app. Some migrants lost their phones or had them stolen on difficult journeys to the border.

All this means the fate of migrants—many of whom are fleeing extreme poverty and violence—hinges largely on a smartphone lottery system. The assumption that migrants fleeing danger will have ready access to a smartphone is misguided, immigration advocates say. “Imagine if your whole life was based upon whether or not your family had enough money to get an expensive phone. People are literally choosing a phone over food,” says Priscilla Orta, supervising attorney at Project Corazon, a program by Lawyers for Good Government, a human rights advocacy organization that runs pro bono legal service programs.

In theory, an individual fleeing persecution just needs to present themselves to immigration officials and explain they have a fear of being returned to their country of origin for a shot at asylum, says Chelsea Sachau, an attorney at the Arizona-based Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project. But in practice, Sachau says when her clients have approached immigration officials to explain that they can’t read or speak Spanish or that they don’t have a smartphone, they have been turned away and told they need to get one and figure it out. “The CBP One app is a really dangerous threat because it does violate the whole concept that people can access the process in a fair way and an equitable way,” she says.

Following criticism of the app, which was officially rolled out in Oct. 2020 but has been more widely used since Jan. 2023, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) announced some changes earlier this month, including a scheduling system that will allow users to request an appointment for 23 hours each day, instead of at a short designated time. The agency said this was aimed at reducing time pressure. Before this change, navigating the app was chaos, some immigration attorneys say. “It essentially was like if Taylor Swift concert tickets for last fall happened every single morning. But instead of for concert tickets, it was your ticket to safety,” Sachau says.

CBP did not respond to a request for comment about ongoing criticism of the app.

Despite the changes, migrants and their advocates are still calling for providing additional tools to access asylum. Among them: the ability to walk up to the bridge and request to legally go through the asylum process, even if you haven’t gone through the app. “The administration likes to paint (the app) as an orderly way of handling things. But what is so un-orderly about a line at the bridge that does not require a phone?” Orta says. “We’re all for providing various tools of access; this could be one of many tools but not the sole tool.” Orta has also pushed DHS to release a web version of the appointment system that can be accessed through a computer, which could make it easier for migrant aid groups to help. A paper form to submit a request could be useful, too, she says.

In the meantime, the app is not always accessible for those in the most perilous situations.

Among those waiting in Mexico is 51-year-old Marco, who is HIV-positive and has run out of medications. His wife Noelia, 39, has recently undergone surgery for breast cancer and also has run out of medications. Speaking to TIME on WhatsApp, he said they are desperate. “My family is suffering from hunger, we’re running out of money…the app hasn’t worked, it hasn’t worked for anyone, we don’t know what else to do,” he said. “As the father of the family I am responsible for them all. We are human beings, please help us.”

Marco and Noelia—the same legal advocates aiding Diego also requested withholding their last names—aren’t alone. Maribel Hernández Rivera, a deputy national political director at the ACLU, was part of a recent delegation organized by the Haitian Bridge Alliance that visited migrant shelters along the border. She recalls meeting a woman from Honduras inside a migrant camp. Her six-year-old daughter had a fever. She said her phone was stolen and she doesn’t have the money to buy a new one.

-With additional reporting by Vera Bergengruen

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Sanya Mansoor at sanya.mansoor@time.com