For decades, women have received changing advice about who should mammogram screenings for breast cancer, and how often. The guidelines have been especially variable for women in their 40s—leading them confused about what schedule is right for them.

The recommendations may be changing yet again. From 2016 until now, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), a government body of experts that regularly reviews data on important health issues, has advised women ages 40 to 50 to make personalized decisions about their screening schedule after discussing their health history and risks for breast cancer with their doctors. But in May, the task force concluded that most women in their 40s who are at average risk for breast cancer should get mammograms every other year. That means that the task force now believes all women ages 40 to 74 should be screened every other year, since the group already recommends that women 50 to 74 get screened every other year. The USPSTF is accepting public comment on the new proposed guidelines until June 5, 2023 before making a final recommendation.

The USPSTF isn’t the only health group with mammogram guidelines; other professional organizations recommend even more frequent screenings—but these can come with risks. Here’s what women should know about the potential changes and how it affects them.

The data behind the new guidelines

The proposed updated guidelines reflect the latest data, says USPSTF member Dr. John Wong, a professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine. Since the group’s last recommendation, new data show that the risk of breast cancer for women in their 40s is higher than previously thought. “More women than ever before are developing breast cancer in their 40s,” he says. “From 2015 to 2019, the latest years for which we reviewed data, every year an additional 2% of women were developing breast cancer in this age group.”

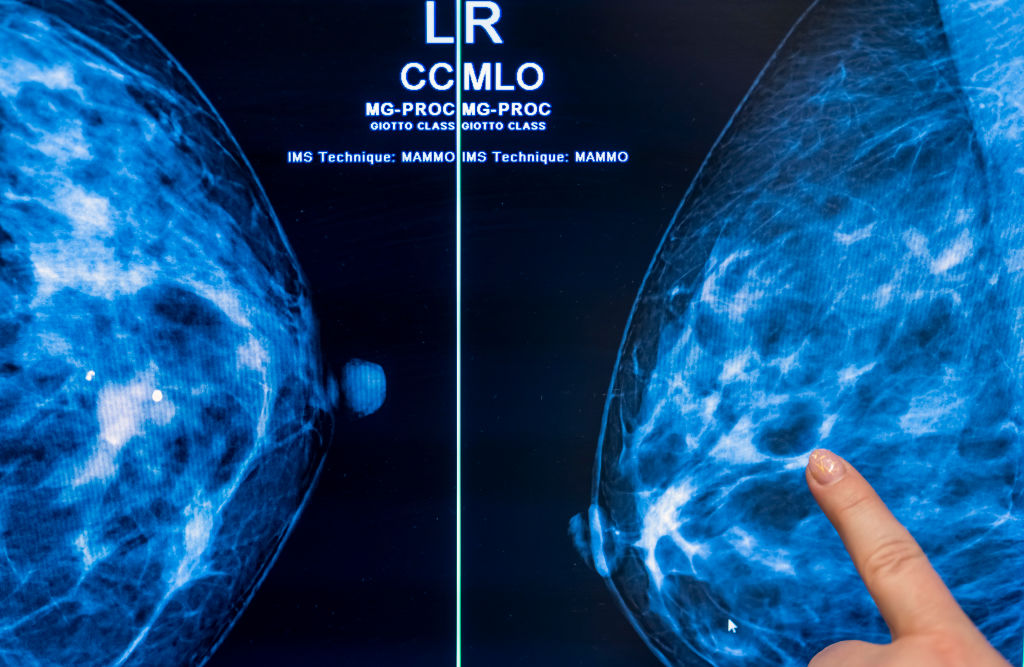

More sophisticated forms of imaging have also helped to support the readings from X-ray-based mammograms, and give doctors additional information to make more accurate interpretations and lowering the risk of detecting false positive growths.

The task force also looked at research that forecasted what would happen to breast cancer rates if current trends continued. They combined that with the impact of new, more targeted cancer treatments. “Starting screening every other year at age 40 could increase the number of lives saved by as much as 20% compared to the 2016 recommendations,” says Wong. “The benefit is even greater for Black women, who are more likely to get aggressive cancers and are more likely to die of their breast cancers.”

Data that the task force reviewed show that Black women are 40% more likely than white women to die of breast cancer, despite similar screening frequencies between the two groups. That may be due to the fact that it takes longer for Black women to receive follow-up care after getting a mammogram. “We are calling on and urging health care providers to make sure all women have timely follow up and timely, effective, and equitable high-quality treatment for their breast cancer,” says Wong. He says more research is needed to understand breast cancer trends among different racial and ethnic groups, including Hispanic and Asian women, and the impact that mammogram screening can have in lowering cancer incidence.

Is even more screening better?

How much screening is enough remains a highly debated question. Groups other than the USPSTF, for example, recommend that women in this age group get screened even more frequently. The American College of Radiology recommends that all women start getting mammograms beginning at age 40 every year to monitor for breast cancer. The American Cancer Society, on the other hand, advises most women to start screening at age 45 with annual mammograms, then move to getting them every other year at age 55.

But such schedules are too frequent, the USPSTF experts found. The benefits of screening and catching cancer early should be balanced by the risks of over-diagnosis and over-treatment, which increase with yearly mammograms from that young age and can detect small and often benign lesions that might not become malignant. Addressing them comes at considerable psychological, physical, and economic cost, the group concluded after analyzing available data.

Still, some breast cancer experts say the alternate year screening may not be enough, especially for detecting the aggressive cancers that women of color tend to develop. Dr. Daniel Kopans, professor of radiology at Massachusetts General Hospital who has argued that the data support yearly mammogram screening for women 40 to 74, says “the present recommendation is a much-delayed win for women. We will never know how many lives have been lost by those who followed the previous USPSTF guidelines.” Some studies suggest that if women in their 30s waited until age 50 to get mammograms every other year, as the current USPSTF guidelines currently recommend, that up to 100,000 would die of breast cancer because their cancers would not have been caught early. “Why would we want to give cancer an extra year to grow, spread, and become incurable?” says Kopans.

Experts considering the economic and psychological costs of repeat screens and over-diagnosis, however, say that yearly screening adds $1.2 billion of additional cost for the U.S. health care system each year, and that more regular mammogram guidelines only widen the gap between the insured—for whom these services are covered—and the uninsured, who may not be able to afford them and therefore skip them.

Personalized screening recommendations are the future

Using one main criterion—in this case, age—to make a blanket recommendation for all women within a certain risk group will never work perfectly. That’s why some breast-cancer experts are advocating a shift away from general, population-based advice toward more personalized screening guidelines that emphasize each woman’s individual health and family history. This, they say, will better determine the best time for any given woman to start receiving mammograms and how often to get them.

That may be on the horizon, as more women take advantage of genetic sequencing to identify their particular cancer risk, and researchers gain deeper knowledge about how various risk factors—from genetics to family history and environmental exposures—contribute to a condition like breast cancer.

But for now, the broader population based advice can serve as a starting point for helping women and their doctors determine when and how mammogram screenings can help them.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com