A team of politicians, academics and legal experts in California voted to move forward with a proposal on establishing reparations, including compensation, for millions of Black Californians this week.

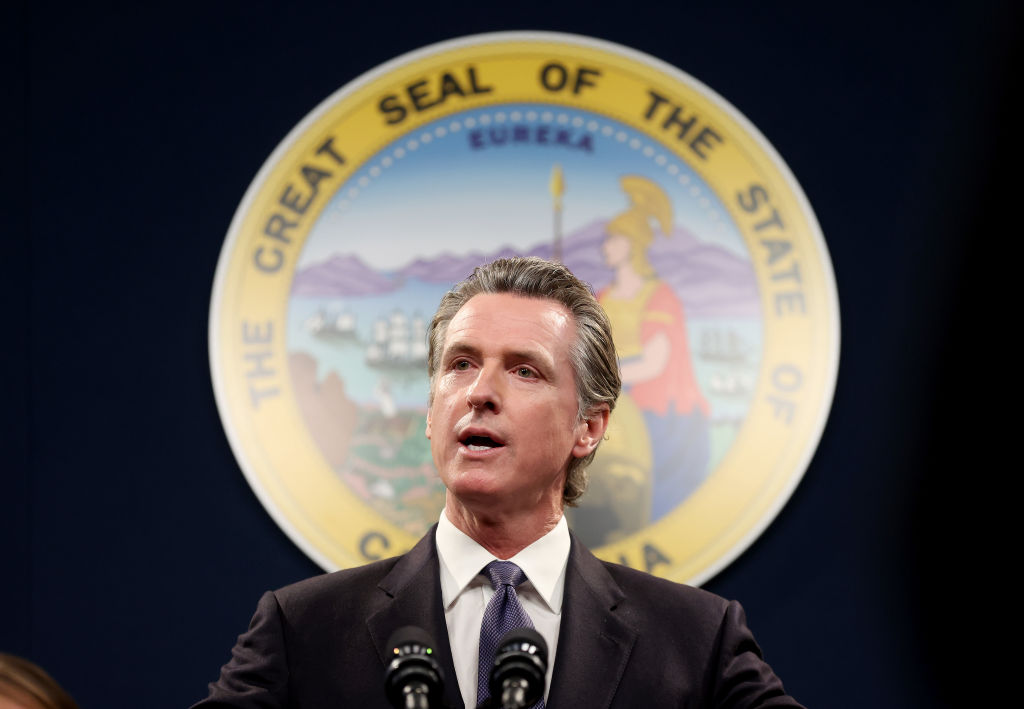

The group, named the Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans, spent two years studying the history and ongoing systems that disadvantage descendants of enslaved people, and will make final recommendations this summer on how to remedy the harm imposed by state actions. It will then be on the state legislature and Governor Gavin Newsom to pass laws implementing those recommendations.

The reparations would be a landmark step for racial equality in the U.S., and perhaps inspire similar efforts across the country. In a proposal draft initially published in March, the task force recommends compensation payments for eligible residents that could reach up to $1.2 million for some, according to news estimates.

The task force evaluated the exact amount of monetary loss for Black Californians, based, in part, on inequitable housing, infrastructure, and legal practices that have limited their ability to gain wealth.

On Wednesday, Newsom said the recommendations were “a milestone in our bipartisan effort to advance justice and promote healing.” He hasn’t commented on whether he plans to support the task force’s recommendations.

“Dealing with the legacy of slavery is about much more than cash payments,” Newsom said in a statement.

Here’s what to know about the reparations.

Reparations on the agenda

In September 2020, Assembly Bill (AB) 3121 established the “Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans,” in California and nine members were appointed. Task force member Jovan Scott Lewis, an economic anthropologist who researches reparations, explains that years of grassroots lobbying led to AB 3121, but George Floyd’s murder and the nation’s racial reckoning movement in 2020 was the bill’s catalyst.

Over the task force’s tenure, the team hired five economists and public policy experts to measure the economic loss of Black Californians due to housing discrimination, health harms, the devaluation of Black businesses, mass incarceration and over-policing since the state’s founding in 1850, according to attorney Kamilah Moore, the task force chair.

“All of the data they [experts] acquired supports the claim that the state of California was specifically culpable in perpetuating those harm areas, and contributing to the economic loss of African-American Californians,” Moore tells TIME.

Using the experts’ data, the task force’s draft report says in areas such as housing discrimination, $3,366 annual payments would adequately compensate eligible Black Californians for each year spent living in the state between 1933 and 1977. For mass incarceration and overpolicing it would be, $2,352 for each year of residency in California between 1971 and 2020. And for healthcare disparities, it would be $13,619 for each year of residency, based on 71-year life expectancy.

According to CalMatters, a 19-year-old who moved to California in 2018 could be owed at least $149,799, while a 71-year-old who lived in California all their life could be owed about $1.2 million.

The task force agreed with experts’ findings, but it will ultimately be up to lawmakers to use those numbers or adjust them if they decide to dole out financial reparation. “We’re not saying that it’s how much we think the African-American community should or should not be given. We’re saying that’s actually how much they’ve lost,” Lewis says.

The task force voted to recommend offering reparations only to descendants of enslaved African-Americans or descendants of free Black people living in the U.S. in the 1800s. A heavily-debated idea, the task force opted to exclude Black immigrants who arrived after 1899 and their descendants. About 80% of Black Californians or 2.6 million residents would be eligible, according to CalMatters.

At the task force’s hearing on May 6, the committee recommended that the state also issue a formal apology to freed African slaves and their descendants to “pay tribute to victims and encourage communal reflection.” In its draft report, the task force references human rights law and historical precedent, such as reparations for indigenous communities in the U.S. and Canada, as part of its justification for reparations for Black Californians.

The group also voted in favor of endorsing the creation of a new state agency that would provide direct services to descendants of enslaved people and oversight to existing agencies, along with continuing work the task force began.

The task force’s final report will be published on June 29.

The demand and criticism over reparations

California, like most states, has a history of discriminatory practices like redlining, which prevented minorities from accessing mortgages and other loans for residing in “hazardous” neighborhoods—considered so for their minority makeup.

Reparations advocates also point out the state government’s previous use of eminent domain (the government’s right to take private property) to seize Black-owned property for government projects. From commercial centers to highways and train lines, the practice tore Black communities apart, while predominantly white ones fared alright.

“You get on a highway every day to go to work. You get on public transport,” Lewis says. “If those two things were developed because the Black community had to be demolished, then you benefit from that.”

Research has also pointed to discriminatory policing and imprisonment of Black Americans, plus substantial inequality in healthcare.

Although slavery was never legal in California, it was still practiced and as many as 1,000 enslaved people may have been in the state before the civil war, according to scholars. Lewis says that reparations are meant to address the trickle-down effects that slavery inflicted. He hopes that if compensated, eligible residents will be able to move back to neighborhoods that they were forcibly removed from or that gentrification pushed them out of.

Opponents to financial reparations argue that taxpayers shouldn’t have to foot the bill, but Lewis notes, “Individuals who pay taxes have to understand that they live in a system of governance, where their taxes fund the state, and their state, historically and continues to have policies and practices that discriminate against African-Americans.”

Along with the final draft of the committee’s report, the task force will hold a panel in Sacramento with eligible Californians who can speak on their lived experiences and how reparations would benefit them. The findings will then be presented to the state legislature by July 1, and the force will then disband. “After that, it’ll be up to the legislature to turn our recommendations into actual legislation,” Moore says. “And then it’ll be up to the Governor to sign them into law.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com