A federal jury in New York on Tuesday found former President Donald Trump liable for sexually abusing writer E. Jean Carroll in the 1990s and for defaming Carroll by branding her a liar after her allegation was made public in 2019. The jury ordered Trump to pay $5 million in total damages, a decision he says he plans to appeal.

In the U.S., it’s rare for a politician—let alone a former President—to be sued for defamation. Politicians make false claims all the time, especially about opponents in the heat of campaigns. But when it comes to statements made about public figures, the First Amendment and legal precedent set a high bar for proving “actual malice” and “reckless disregard of the truth.” The costs of taking a defamation case to court, combined with the low chance of success for relatively little reward anyway, have proved a reliable deterrent. On the other hand, Trump, who is campaigning once again for the presidency, has actually mused about “opening up” American libel laws to make it easier for politicians like him to go after critics.

What might such a system look like? In many ways, it’s what’s already happening in Malaysia, where it’s almost rare for a high-profile politician not to be embroiled in a defamation case.

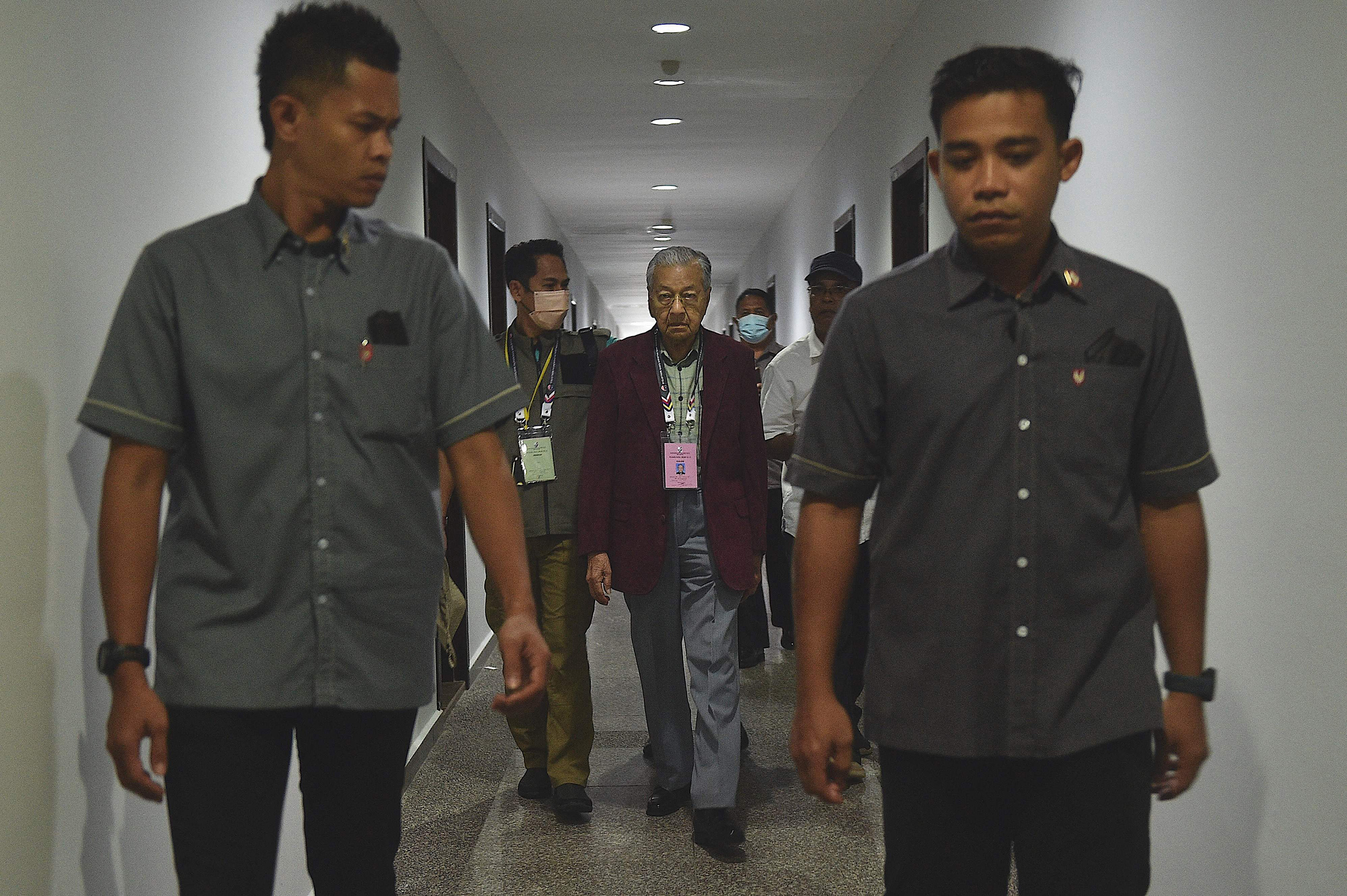

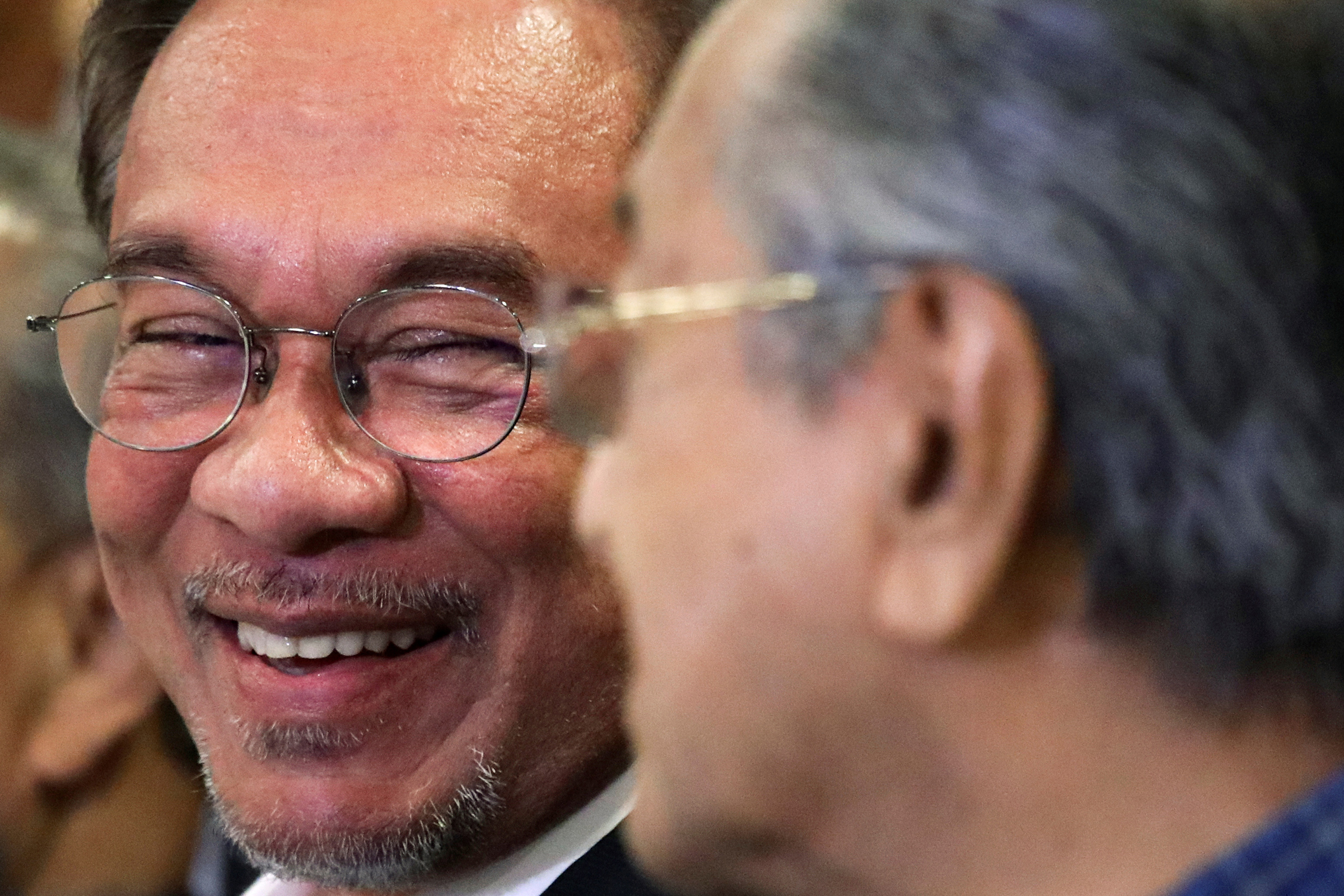

Just last week, the country’s former Prime Minister sued the current Prime Minister—entangling two of the most prominent political figures in the Southeast Asian nation of 33 million people. On May 3, 97-year-old Mahathir Mohamad, Malaysia’s longest-serving leader, filed a 150 million Malaysian ringgit ($33.8 million) defamation suit against his longtime political foe, incumbent Anwar Ibrahim over comments Anwar made in a March 2021 press conference. Anwar had implied that Mahathir used his former perch to enrich himself and his family, which Mahathir denied. Anwar made the allegation before last year’s general elections, in which Mahathir would ultimately suffer his first electoral defeat in 53 years and Anwar would take the country’s top office. Mahathir claims Anwar’s comments marred his reputation as a respected statesman.

“Let the lawyers handle it,” Anwar reportedly said in response to the lawsuit, according to the state news agency.

It’s not the first defamation case involving the two, and not even the first against a sitting Prime Minister in Malaysia. Mahathir’s latest legal action is just one of several defamation suits involving high-profile politicians in the country. In fact, an analysis by TIME finds that every Malaysian Prime Minister since 2009 has faced at least one such complaint at some point in their career, often lodged by political opponents.

Many Malaysian politicians argue that defamation lawsuits are their only recourse against people who spread disinformation about them, though Ross Tapsell, associate professor and director of the Malaysia Institute at Australian National University, says defamation laws are commonly used to silence critics.

“One of the big concerns in Southeast Asia is that defamation laws tend to be used by rich and powerful individuals, often to suppress commentary from poor and weaker groups and individuals in the region,” Tapsell tells TIME. He points to the judicial inequity in the country, noting that it’s rare to hear of defamation cases between members of the Malaysian general public. As for the lawsuits that do occur, he says—even if they’re contested between two members of government—they create a chilling effect that supplements the already stringent laws against freedom of speech in the country.

How Malaysia’s defamation laws work

In Malaysia, defamation can be prosecuted as a civil or criminal offense. Civil defamation is punishable by law under the Defamation Act of 1957, while criminal defamation is covered by Sections 499 to 502 of the country’s Penal Code. Those convicted of criminal defamation may be fined or imprisoned for up to two years, whereas successful civil claims can result in the awarding of financial damages and, in some cases, formal retractions and apologies.

Guok Ngek Seong, a lawyer who has handled defamation cases in Malaysia, says “any statement which has the tendency to bring down a reputation of the person, usually, from the eyes of a reasonable person” can be considered defamatory. Most politicians take the civil route, Guok says, which he believes is wise.

“You may as well try to vindicate yourself through civil action rather than criminal,” Guok says. With criminal cases, he reasons, “you are also basically wasting the taxpayers’ money by asking the authorities to investigate the case, which could have been settled by way of a civil case.”

Guok says defamation suits can serve to vindicate those whose image has been unjustly impugned. But he laments that it’s become too common a recourse for Malaysian public figures of late. “Gone were the days that the politicians took filing defamation suits against any party especially the[ir] political opponents as something serious,” he tells TIME. “They should be taking responsibilities if they lose the defamation suit commenced by them,” he says, but instead, regarding that aspect at least, some appear “thick-skinned.”

There are limits, however. For one, defamation only applies to living individuals. And for its part, Guok notes, the Federal Court held in a ruling last year that political parties, as an entity, do not have any reputation to protect.

Still, Tapsell says, with Malaysia’s defamation laws, it’s becoming “very common to see that politicians will use the courts in order to get what they want … or even to threaten to use the courts can be enough in some cases.”

Here are just some of the publicized defamation cases involving—on one end or the other—the most recent Malaysian Prime Ministers.

Najib Razak (Prime Minister, 2009-2018)

Since 2015, Najib Razak has been locked in litigation with lawmaker Tony Pua over comments the latter made linking Najib to the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) scandal. Najib’s 2015 suit against Pua is believed to be the first case of a sitting Prime Minister suing a lawmaker for defamation in Malaysia.

Najib is also due in court for a couple of defamation cases. In 2021, he became the defendant when former health minister Dzulkefly Ahmad took issue with a Facebook post he made that accused Dzulkefly of nepotism and cronyism. That case will go to trial in June 2024. Also in 2021, Najib sued former Attorney General Tommy Thomas over statements in the latter’s book that allegedly overstate Najib’s ties to the 2006 murder of Mongolian Altantuya Sharibuu. That trial begins in September.

And just last year, Najib said he had sued Shamsul Iskandar Mohd Akin, a former deputy minister and current senior political secretary to Prime Minister Anwar, over allegedly false details in a post on Facebook about Najib’s role in the 1MDB scandal.

Najib was voted out in 2018 over the 1MDB scandal. More than 40 charges were filed against Najib for corruption, and he was convicted of several charges and sentenced after losing on appeal to 12 years last August, while a separate but related $436-million trial remains underway.

Mahathir Mohamad (2018-2020)

Anwar, after being sacked as Mahathir’s former deputy prime minister during the latter’s first term from 1981-2003, filed a suit in 1999 against his mentor for slander. The case was based on Mahathir’s September 1998 statements on Anwar’s alleged sexual misconduct that prompted his firing that year. Anwar claimed 100 Malaysian ringgit ($26 million) in damages, but the case was dismissed. He was eventually charged with sodomy twice. Anwar was convicted for the first but Malaysia’s federal court overturned the ruling, and Malaysia’s King Sultan Muhammad V pardoned him in 2018 for the second.

Anwar filed another suit against Mahathir in 2006 similar to his 1999 one, in hopes of getting even with his former mentor. The case was based on comments Mahathir made in September 2005, alleging that Anwar was gay and that his orientation could be a threat to Malaysians should he become Prime Minister. The case was dismissed in 2007.

Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, president of Mahathir’s former political party United Malays National Organization (UMNO), filed a defamation case against Mahathir in 2022. Zahid’s suit was based on Mahathir’s statements that Zahid sought to have his dozens of corruption-related court cases dropped by being friendly with Mahathir. Mahathir filed a separate defamation suit against Zahid for remarks over his ethnicity. As of April 2023, a High Court official has suggested an out-of-court settlement for the two cases.

On May 3, Mahathir filed a suit against Anwar for alluding in a speech at a March 2021 political event that a former leader—who remained unnamed though Anwar mentioned his two stints as Prime Minister for “22 years and (another) 22 months”—had used his post to amass wealth.

Muhyiddin Yassin (2020-2021)

Former Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin is involved in two ongoing defamation cases filed against him. In 2022, Anwar, as sitting Prime Minister, sued Muhyiddin over statements he made in December 2021 about Anwar making a large salary as a local government adviser. And last March, former finance minister Lim Guan Eng lodged a complaint accusing Muhyiddin of maligning him three times by repeating an allegedly false claim about Lim revoking the tax exemption status given to a renowned Muslim charitable organization.

Ismail Sabri Yaakob (2021-2022)

In 2015, former lawmaker Nurul Izzah Anwar sued Ismail Sabri Yaakob, then rural and regional development minister, and the Inspector-General of Police for statements that painted her as a traitor to Malaysia. Ismail Sabri and his co-accused ended up having to pay Nurul 850,000 ringgit ($193,000) in damages in 2019. Losing the case, however, didn’t stop Ismail Sabri from becoming Prime Minister a few years later.

In 2022, amid a shake-up in Malaysia’s parliament, Ismail Sabri filed a suit against former UMNO supreme council member Lokman Adam. Lokman had said on a video posted to social media that Ismail Sabri met with opposition party leaders, and let down his own party’s interests in order to try to stay in power. As of January, Ismail Sabri obtained an injunction to take down the video, and Lokman has in turn filed his own counterclaim against Ismail Sabri, alleging that he’s suffered as a result of the original case.

Anwar Ibrahim (2022-)

Then Inspector General of Police Musa Hassan sued Anwar for a police report Anwar produced in July 2008 that alluded to Musa and the police fabricating evidence to cover up Anwar’s beating in 1998. In 2012, Musa withdrew the case.

In 2022, Anwar filed a suit against lawmaker Sanusi Nor for remarks that suggested he was of immoral character, had abused power as an MP, and was not “a good Muslim.” Anwar claims that his 2018 full pardon had cleared his reputation.

Correction, June 9

The original version of this story misspelled a lawyer’s name. It is Guok Ngek Seong, not Guok Ngek Song.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com