In a rapid shift since last year, over a dozen states have moved to legalize fentanyl test strips. The change is one that harm reduction proponents argue is necessary during an era where fentanyl overdose is a leading cause of death in American adults under 45.

After years of advocacy from medical professionals and Democratic politicians, including the Biden Administration, fentanyl test strips are finally becoming less polarizing—but only to an extent. Staunch conservatives were deeply opposed to the strips—which allow people to test drugs for traces of fentanyl—for years, arguing that they enabled drug abuse. A mass of Republican-controlled legislatures, including Utah, Kentucky and Mississippi, have backtracked in recent months and welcomed policy to decriminalize the strips.

“If political leaders are serious when they say that this [the opioid epidemic] disturbs them, then an easy first step—it’s just one step, there are many other things that can and should be done—but an easy first step is to make fentanyl test strips legally available,” Dr. Jeffrey Singer, a surgeon and senior fellow in the Cato Institute’s health policy department, tells TIME.

Test strips are available in more than 30 other states and Washington D.C., according to recent counts. In states where they’re legal for distribution, the strips are up for sale in pharmacies and frequently handed out for free at public health department centers, harm reduction clinics, and even college campuses.

Support for the strips has become fairly bipartisan, but small clusters of conservative lawmakers have consistently opposed legislation to increase access to the strips, such as in Texas where bills have been stalled for weeks.

“I think it’s an absolute no-brainer that they [test strips] are essential tools for public health and reducing overdoses,” says Jennifer Carroll, a medical anthropologist of substance abuse impact and policy at North Carolina State University. “Anyone who questions that utility hasn’t left the house very much because this is not a controversial topic.”

The argument for testing

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid—50 to 100 times more potent than heroin—that has transformed the illicit drug landscape in the U.S. since over the past decade. Over 40% of counterfeit prescription pills had lethal amounts of fentanyl in 2021, according to the Drug Enforcement Agency. Even in small amounts, it can be deadly, and more than 150 people die from synthetic opioids overdoses daily, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

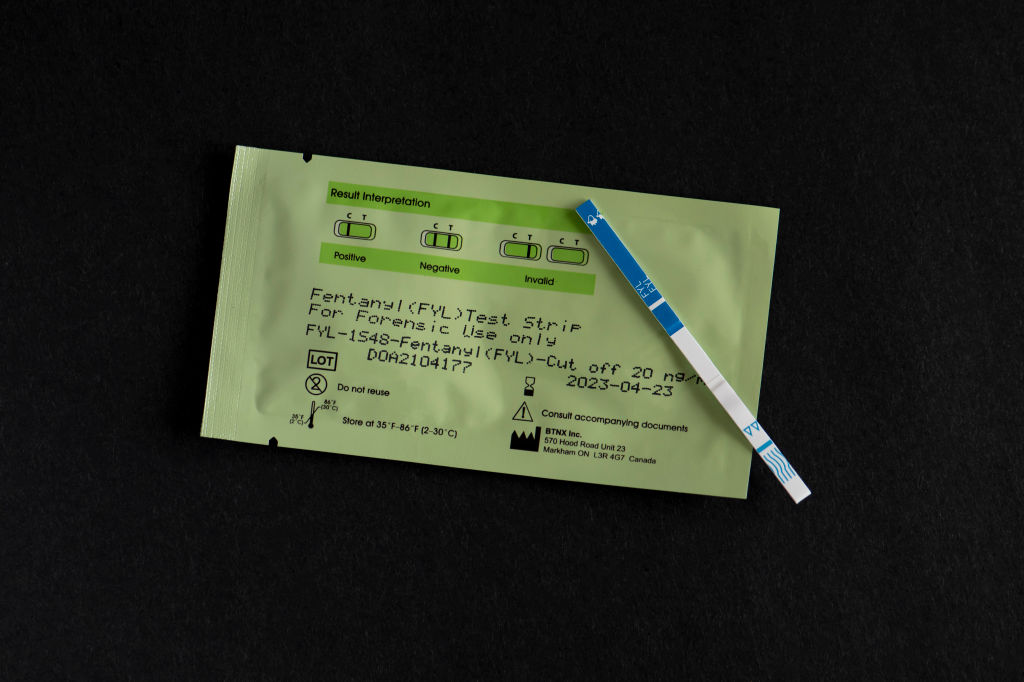

Fentanyl test strips are often regarded as a “low-cost, high-impact” harm-reduction strategy—they are about 97% accurate; are compatible with most injectable, powder, or pill drugs; and cost only $1 per test. Anyone using heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, ecstasy, or other substances can dissolve a tiny amount of their product—less than the size of a grain of rice—in water, dip the strip in the solution and wait a few minutes for the test result.

A major reason for the rise in fentanyl overdoses is substance users not realizing that their products are laced with fentanyl. “We hear story after story of people obtaining drugs on the black market that they don’t think is fentanyl,” Singer says.

70% of drug users who learn that their products contain fentanyl will alter their drug habits, according to a 2018 Johns Hopkins study. That might mean changing their purchasing practices, taking smaller doses, and/or keeping Naloxone (an opioid overdose-reversal medication) on hand.

The CDC, the American Medical Association, and numerous other agencies and researchers have endorsed the use of fentanyl test strips, and substantial research shows their value in overdose prevention. The strips were first approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a device to detect fentanyl in urine, but harm-reduction activists discovered the secondary, off-label use for testing drugs a few years ago, according to Singer.

Reluctance to legalize fentanyl test strips

Despite the off-label use, which is not FDA-approved, the test strips were considered drug paraphernalia and outlawed in almost every state for personal use until decriminalization efforts took off over the past two years. Under federal law, “paraphernalia” means any equipment or product that is primarily intended to introduce a controlled substance into the body.

When the test strips emerged as a viable drug checking option in 2019, opposition was much stronger than it is today, especially among vocal conservatives. Most argued that the strips would encourage drug abuse. As Elinore McCance-Katz, Donald Trump’s assistant secretary of Health and Human Services for Mental Health and Substance Use, phrased it in 2019, “Let’s not rationalize putting tools in place to help them continue their lifestyle more ‘safely.’” McCance-Katz also suggested that some people, seeking a stronger high, would use the strips to actually seek out fentanyl-laced drugs.

Carroll, the medical anthropologist, acknowledges that “it’s a very important question to ask—are there unexpected negative outcomes?” But, she adds, “Fortunately, I would say that these questions are well answered,” Carroll says. “This works. It helps us save lives. It doesn’t have negative impacts on the community, or on individuals.”

In GOP-led states, many governors are feeling the heat to take action against the fentanyl crisis, especially across the southern U.S., where opioid death rates have been particularly high. Part of their tough-on-crime approach to the issue has involved speeding up policy to decriminalize the strips.

In Texas, where the strips are still illegal for personal use and ownership and can result in a Class C misdemeanor or a $500 fine, Governor Greg Abbott, a Republican, took a new stance in December, encouraging state lawmakers to decriminalize them and arguing that it could, along with other harm-reduction strategies, “save hundreds, if not thousands of lives just in the state of Texas on an annual basis alone.” Abbott designated the fentanyl crisis as an emergency in February, permitting Texas legislators to pass a policy to address it within the first two months of the session.

Since then, multiple bills related to the cause have circulated through the state legislature. One, HB 362, proposes removing fentanyl test strips from the state’s list of drug paraphernalia—and it passed unanimously through the House. Despite bipartisan support, the Senate has not yet been able to vote on the bill while it remains stuck in a Republican-led committee. Protestors gathered at the office of the committee leader, Senator Joan Huffman, last week, demanding that lawmakers take action.

Meanwhile in Florida, the House of Representatives worked together in a rare bipartisan show of support to pass SB 164, decriminalizing fentanyl test strips on Wednesday. The bill is on its way to Governor Ron DeSantis’s office, who is expected to approve it. Following a substantial campaign effort from parents who lost children to fentanyl overdose, the Kansas legislature passed a similar bill in late April, SB 174, which would remove fentanyl test strips from the state’s list of drug paraphernalia. The bill was sent to Governor Laura Kelly’s office on Friday, who has voiced her support for such legislation and is expected to sign it into law.

“Policymakers can’t be experts on everything,” Carroll says, arguing that the debates stalling test strip legalization have been too moralized, ignoring scientific data. “I would encourage our policymakers to listen to experts. Those include public health researchers, harm reduction professionals and people who use drugs who know better than anyone what they need in order to be safe and healthy.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com