In late January, a mysterious balloon was spotted floating over U.S. waters and later hovered around Montana above missile sites. The balloon, which turned out to be a surveillance balloon from China, was shot down when it was safely off the coast of South Carolina. Last week, another unidentified balloon was tracked over Hawaii, raising apprehension and curiosity yet again. On Tuesday, a defense official said that balloon posed no danger to aviation or national security.

This is not the first time balloon incursions have been of concern to the American public. In fact, a balloon floating into U.S. airspace once caused fatal consequences: May 5 marks the 78th anniversary of a relatively unknown tragedy caused by balloon bombs at the tail end of World War II, when one set off a deadly explosion in the pine forests near Bly, Oregon.

It was a beautiful spring day when Rev. Archie Mitchell, the new minister at the Christian and Missionary Alliance Church in Bly, Oregon and his pregnant wife Elsie, invited five Sunday school students on a picnic and fishing trip. That halcyon jaunt would end as the only lethal attack by an enemy on the continental United States during World War II.

While the pastor parked the car, the children and Elsie Mitchell got out of the car and headed toward Leonard Creek. He heard his wife call out, “Look what we found. It looks like some kind of balloon.”

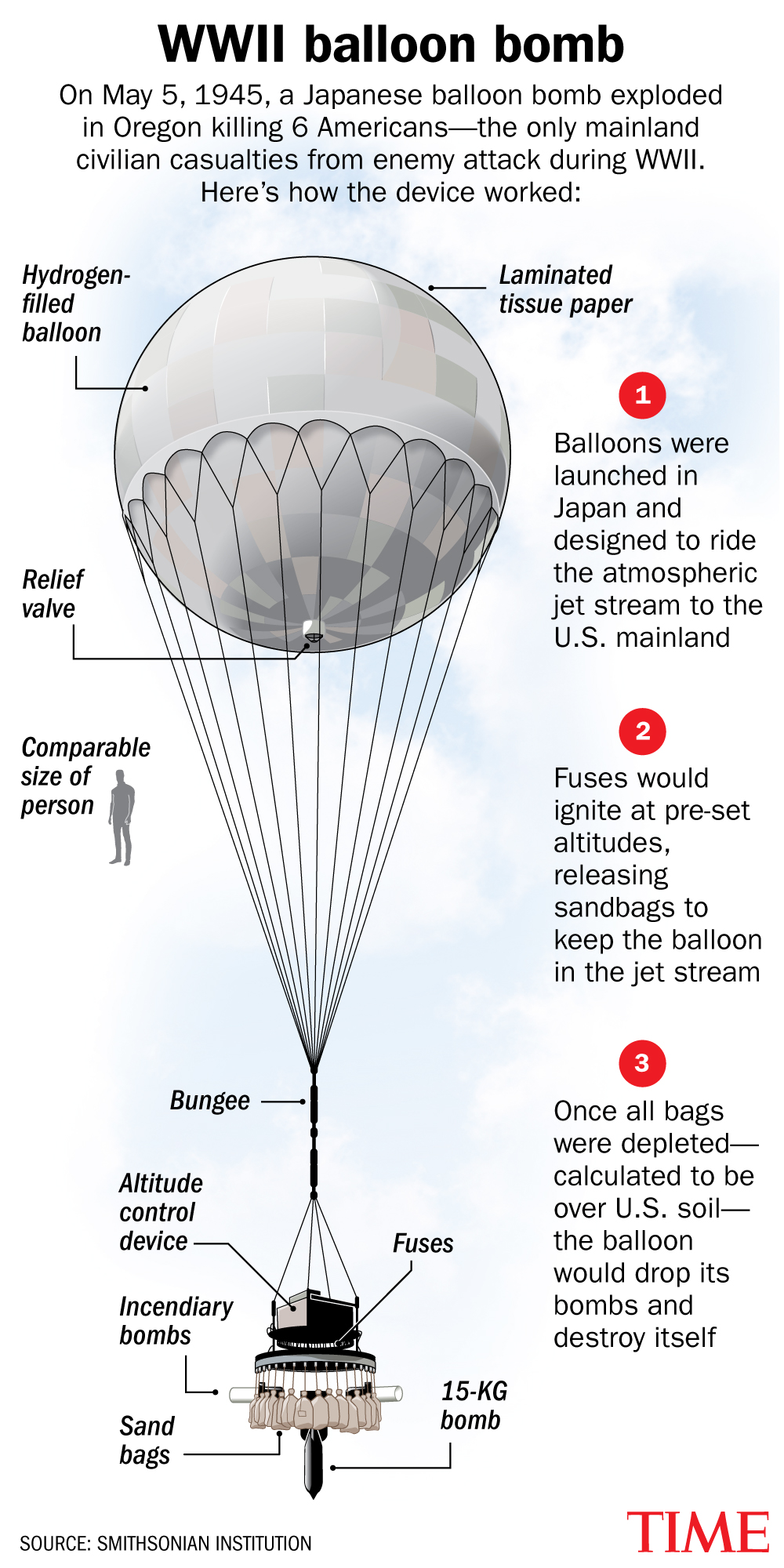

What Elsie and the children didn’t know—but Archie Mitchell did—is that the Imperial Japanese Army had developed an incendiary balloon bomb. This bomb was transported by jet stream 5,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean by hitching a ride on a balloon, and they had launched about 9,300 of them toward the Western United States.

Just as Archie was about to issue a warning, there was a fierce explosion. He was spared the brunt of the blast, but was slightly injured when he rushed to the scene and tried to extinguish fires on his wife’s clothing. His wife and the children were all killed.

TIME talked to Dr. Ross Coen, who teaches history at the University of Washington and is the author of Fu-go: The Curious History of Japan’s Balloon Bomb Attack on America, about this relatively unknown chapter in American history.

The following conversation has been lightly edited.

What are your thoughts on this anniversary of the Bly explosion?

First of course, we must remember the victims. Five were children, and their adult chaperone was pregnant with her first child. What happened in Bly is a tragedy for those families. In a larger historical sense, the Bly incident was in some respects the first time global war had been brought to the shores of the continental United States. It heralded a new era in which any corner of America could be attacked, an era that would come to include threats as varied as nuclear war and global terrorism.

Are there things about the recent incursion of our air space by the Chinese surveillance balloon that are reminiscent of the Japanese balloon bomb episode during World War II?

What is clear is that the balloons themselves, despite their seemingly low-tech nature in a high-tech world, remain an important tool of espionage and warfare.

The U.S. government has said that the Chinese surveillance balloon did not pose a direct threat to Americans. But during World War II didn’t balloons pose a very significant threat?

The intent of the Japanese balloons in World War II was to cause material damage to the United States and even loss of life, which sadly it accomplished. The main difference between the Japanese balloons of World War II and the recent Chinese balloon is that the Japanese balloons were offensive weapons. I’ve seen nothing to indicate there was any such intent with the Chinese balloon.

When were the first Japanese balloon bombs spotted?

Probably the first Japanese balloon that was observed in flight was in Thermopolis, Wyoming in early December 1944. There were some coal miners who were working that night and they stepped out of a mine and they looked up at the sky and saw the balloon in flight. But they had no idea what they were looking at.

The Japanese balloon story is so fascinating for many reasons, not the least of which is because no one really knew what these things were. For several weeks in late 1944, more than a dozen had arrived before the War Department started to figure out what they were.

When did the U.S. government become aware that these balloons were weapons of Japanese origin?

The awareness dawns on the government in December of 1944, and by January 1945, the War Department knows that it is a Japanese weapon. A few days after that sighting in the first week of December 1944, another balloon is found, this one not in flight but it’s already on the ground in Kalispell, Montana. This balloon has a tag on it that has Japanese writing like a factory production tag.

The balloons had a ballast release system that would keep them at altitude as they are crossing the Pacific. There are thirty odd sandbags, each one weighing about 5 or 6 lbs. Two balloons recovered in Alaska in late December have these sandbags still attached. The sand was sent to the U.S. Geological Survey. And it is determined, due to the composition of the sand inside the bags, that it’s beach sand that really could only have come from handful of beaches around the world that have those specific characteristics, and all of the beaches from which this sand could have been taken were on Honshu, the largest of Japan’s islands.

What were the greatest concerns about damage from these balloon bombs?

From the perspective of the War Department and Army intelligence, the thing that they feared most was biological warfare. They inspected all balloons for any presence of biological agents, something that might spread disease among humans or livestock. Ultimately there never was any biological component to the balloons.

Secondary to that was that these incendiary devices would ignite wildfires in the Western states and the Americans would have to divert resources that might have been used in the Pacific theater. Also, there was the possibility that these balloons would create panic, leading to a weakening of the morale of the American people.

Was the American public informed about the arrival of these offensive weapons in the U.S.?

Word of the very first balloons that arrive, the ones in Wyoming and Montana, did make its way into the press. Small local newspapers covered the arrival of these balloons, but there were very few details. In the first week of January, stories appeared in TIME and Newsweek.

[A January 1, 1945 TIME story disclosed some details about the balloons: “A 70-foot fuse connected to a small incendiary bomb” and “the FBI discovered that the Japanese had obligingly printed a good deal of information on the bag. It had been completed only a few weeks before, on Oct. 31, at a Japanese factory. Japanese characters also revealed the number of hours spent in its manufacture, data regarding work shifts.”]

Once the War Department knows that this is a Japanese offensive weapon in the first week of January 1945, the Office of Censorship institutes a voluntary censorship policy asking all media outlets not to say anything about these balloons. The War Department believes that if information about balloon landings is publicized, it provides a source of intelligence for the Japanese about where and when these balloons are arriving, and it would provide them with an intelligence they could use to modify their launching strategy to maximize effectiveness.

Obviously, there is a dangerous downside to keeping this information from the American public.

The flip side of that is when you’re not telling Americans about these balloons, no one knows how dangerous really are. If a balloon lands in a farmer’s field, who are the first people on the scene? It’s going to be 10-year-old boys who start poking at it with sticks, right? There are instances where townspeople started picking these things up, carrying them into town, stuffing them into the trunks of their cars. It’s remarkable that there wasn’t a fatal incident until the explosion of the bomb in Bly, Oregon in May 1945.

What happened in Bly?

What probably happened is that one of the kids reached down to pick the balloon up and the bomb detonated and six people, Elsie Mitchell and the five children, were all killed.

The six individuals killed in Bly were Elsie Mitchell, who was five months pregnant with her first child; Dick Patzke, 14; Joan Patzke, 13; Jay Gifford, 13; Edward Engen, 13; and Sherman Shoemaker, 11. These were the only fatalities on the continental United States that resulted from enemy action in World War II.

In many ways, the tragedy in Bly, and indeed the Japanese balloon offensive more broadly, showed that the mainland U.S. was not immune from the effects of war. It was nothing compared to the devastation in Europe and the Pacific theater, of course, but it still demonstrated the United States could be attacked from an enemy far beyond its borders.

The Japanese balloons were intercontinental missiles by definition—and that term would take on a whole new meaning in only a few years with the nuclear missiles the U.S. and the USSR pointed at each other. The Japanese balloon attack may have been relatively insignificant by itself, but it heralded a new type of warfare that defines our world to the present day.

Why are we so fascinated by these balloons?

I think there is something mysterious about them. The fact that they are unmanned. That they cannot be steered. They are just sort of free floating up there. There is something about knowing there could be something up there that you cannot see, that you can’t understand, and you don’t know why it’s there. There is something even a little terrifying about that.

Are people still finding remnants of these balloons?

Balloon recovery continued after the war. There were several that were found in the ground in 1946, ‘47, ’48, a couple in the 1950s another one in the 1960s. Just in the last six or seven years there have been two balloons found on the ground in Canada.

We learned after the war, that the Japanese launched about 9,000 balloons from November of 1944 to April 1945. It was estimated both by the Japanese and U.S. military that probably as many as 10% of the total launched would survive the transoceanic crossing and arrive in North America. If 9,000 were launched and 10% made it, that means as many as 900 balloons may have arrived in North America, but there are only about 300 documented recoveries. I would say it’s almost certain that there is still balloon material out there in the wilderness, just laying on the ground.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com