There’s nothing like a block of frozen spinach to make you feel bad about your family dinner. There’s good food and bad food and pretty food and ugly food–and then there’s the frozen-spinach block. By any rights, this is not something you should want to eat. The picture on the box looks lovely, and the very idea of eating spinach is healthy. But what you find inside is a frosty, slightly slimy, algae-colored slab.

Somewhere out there–maybe just a five-minute drive from your house–a farmer’s market is selling fresh, organic leaf spinach that might have been sprouting from the soil an hour ago. This, as we’re told by any number of glossy cookbooks, TV cooking shows, food snobs and long-winded restaurant menus, is how we’re supposed to eat now. It may be more expensive than that frozen block of spinach. And more perishable. And more complicated to prepare. But it’s all worth it because it’s so much healthier than the green ice from the supermarket. Right?

Wrong. Nutritionally speaking, there is little difference between the farmer’s-market bounty and the humble brick from the freezer case. It’s true for many other supermarket foods too. And in my view, dispelling these myths–that boutique foods are good, supermarket foods are suspect and you have to spend a lot to eat well–is critical to improving our nation’s health. Organic food is great, it’s just not very democratic. As a food lover, I enjoy truffle oil, European cheeses and heirloom tomatoes as much as the next person. But as a doctor, I know that patients don’t always have the time, energy or budget to shop for artisanal ingredients and whip them into a meal.

The rise of foodie culture over the past decade has venerated all things small-batch, local-farm and organic–all with premium price tags. But let’s be clear: you don’t need to eat like the 1% to eat healthily. After several years of research and experience, I have come to an encouraging conclusion: the American food supply is abundant, nutritionally sound, affordable and, with a few simple considerations, comparable to the most elite organic diets. Save the cash; the 99% diet can be good for you.

This advice will be a serious buzz kill for specialty brands and high-end food companies marketing the exclusive hyperhealthy nature of their more expensive products. But I consider it a public-health service to the consumer who has to feed a family of five or the person who wants to make all the right choices and instead is alienated and dejected because the marketing of healthy foods too often blurs into elitism, with all the expense and culinary affectation that implies. The fact is, a lot of the stuff we ate in childhood can be good for you and good to eat–if you know how to shop.

Of course, there’s a lot to steer clear of in the supermarket. Food technologists know what we like and make sure we always have our favorites. So alongside meat and fruits and veggies, there’s also pasta, jelly, chips, pizza, candy, soda and more. Is it any wonder two-thirds of us are overweight or obese? Is it any wonder heart disease still kills so many of us?

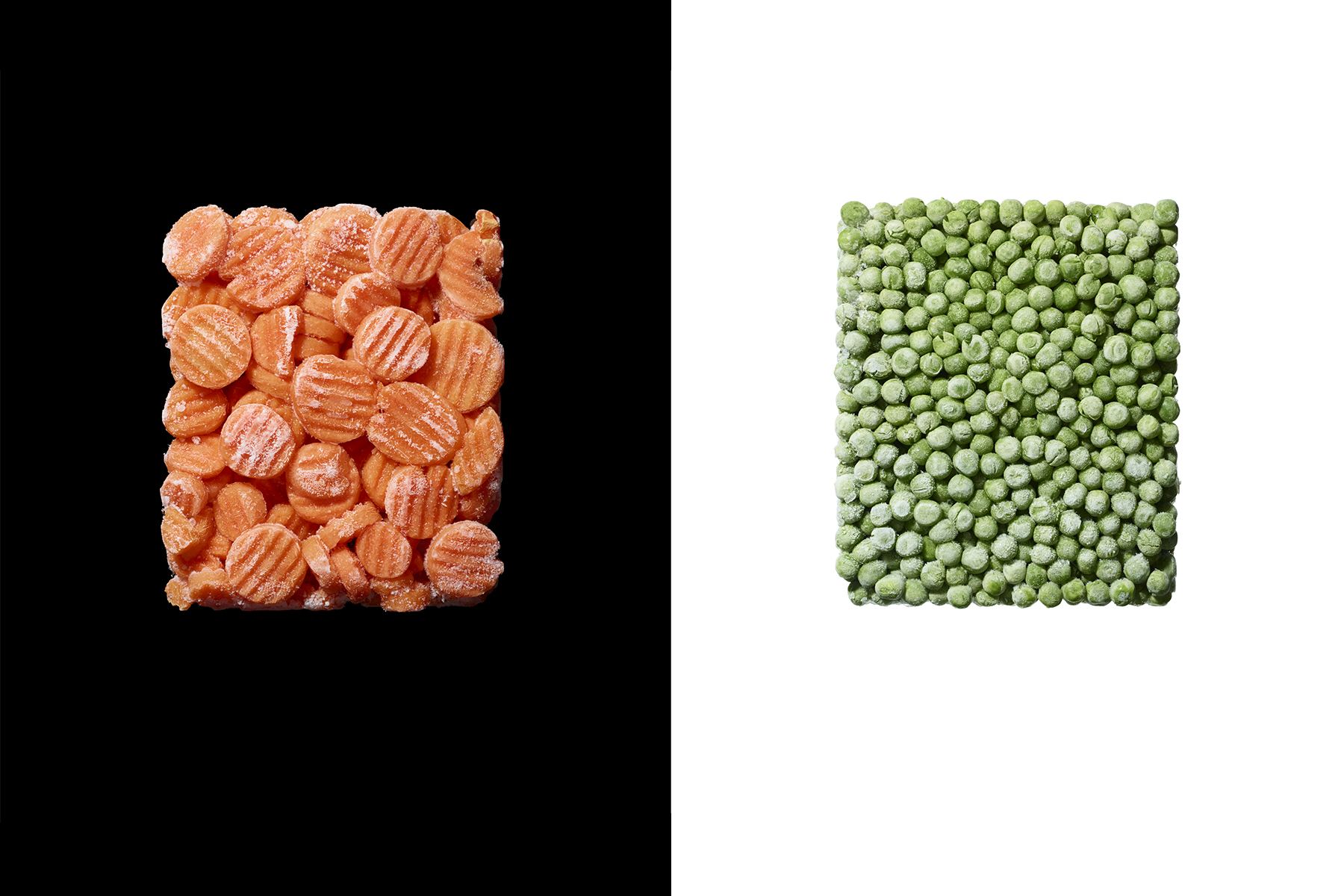

So let’s take a tour of the supermarket in search of everyday foods we can reclaim as stalwarts of a healthy diet. We’ll pick up some meat and some snacks too, and we’ll do a fair amount of label reading as we go. We’ll even make a stop at the ice cream section. (I promise.) But let’s start in the most underrated aisle of all: frozen foods.

Frozen, Canned–and Good?

It was in the 1920s that the idea of freezing fresh vegetables into preserved, edible rectangles first caught hold, when inventor Clarence Birdseye developed a high-pressure, flash-freezing technique that operated at especially low temperatures. The key to his innovation was the flash part: comparatively slow freezing at slightly higher temperatures causes large ice crystals to form in food, damaging its fibrous and cellular structure and robbing it of taste and texture. Birdseye’s supercold, superfast method allowed only small crystals to form and preserved much more of the vitamins and freshness.

In the 90 years since, food manufacturers have added a few additional tricks to improve quality. Some fruits and vegetables are peeled or blanched before freezing, for example, which can cause a bit of oxidation–the phenomenon that makes a peeled apple or banana turn brown. But blanching also deactivates enzymes in fruit that would more dramatically degrade color as well as flavor and nutrient content. What’s more, the blanching process can actually increase the fibrous content of food by concentrating it, which is very good for human digestion.

Vitamin content is a bit more complex. Water-soluble vitamins–C and the various B’s–degrade somewhat during blanching but not when vegetables are steamed instead. Steaming is preferable but it takes longer, and many manufacturers thus don’t do it. The package will tell you how the brand you’re considering was prepared. Other vitamins and nutrients, including carotenoids, thiamin and riboflavin, are not at all affected by freezing, which means you can eat frozen and never feel that you are shortchanging yourself.

Canning is an even older type of preservation; it’s also quite possibly the single most significant technological leap in food storage ever conceived. Developed in the early 19th century by an inventor working for the French navy, canning is a two-step process: first, heat foods to a temperature sufficient to kill all bacteria, and then seal them in airtight containers that prevent oxidation. Not all food comes out of the can as appetizing as it was before it went in. Some fruits and vegetables do not survive the 250F heating that is needed to sterilize food and can become soft and unappetizing. And in decades past, food manufacturers had way too free a hand with the salt shaker. That is not the case any longer for all brands of canned foods. A simple glance at the nutrition label (which itself didn’t exist in the salty old days) can confirm which brands are best.

As with frozen vegetables, fiber and nutrient content usually stay high in canned foods. Some research indicates that carotenes, which can reduce cancer rates and eye problems, may be more available to the body following the routine heat treatment. What’s more, canned foods are bargain foods. In an April study led by dietitian Cathy Kapica of Tufts University, nutritionists crunched the cost-per-serving numbers of some canned foods vs. their fresh counterparts, factoring in the time needed to prepare and the amount of waste generated (the husks and cobs of fresh corn, for example). Again and again, canned foods came up the winner, with protein-rich canned pinto beans costing $1 less per serving than dried, for example, and canned spinach a full 85% cheaper than fresh.

Food on the Hoof, Fin and Wing

I live in a vegetarian household, so I simply don’t have the opportunity to eat a lot of meat at family meals. But I am not opposed to meats that are served in an appropriate portion size and are well prepared. Your first step is deciding what kind of meat you want and how you want to cook it.

There’s no question that free-range chickens and grass-fed, pasture-dwelling cows lead happier–if not appreciably longer–lives than animals raised on factory farms. They are also kept free of hormones and antibiotics and are less likely to carry communicable bacteria like E. coli, which are common on crowded feedlots. If these things are important to you and you have the money to spend, then by all means opt for pricier organic meats.

But for the most part, it’s O.K. to skip the meat boutiques and the high-end butchers. Nutritionally, there is not much difference between, say, grass-fed beef and the feedlot variety. The calories, sodium and protein content are all very close. Any lean meats are generally fine as long as the serving size is correct–and that means 4 to 6 oz., roughly the size of your palm. A modest serving like that can be difficult in a country with as deep a meat tradition as ours, where steak houses serve up 24-oz. portions and the term meat and potatoes is a synonym for good eating. But good eating isn’t always healthy eating, and we’re not even built to handle so much animal protein, since early humans simply did not have meat available at every meal. Sticking with reasonable portions two or three times a week will keep you in step with evolution.

Preparation is another matter, and here there are no secrets. Those burgers your kids (and probably you) love can be fine if they’re lean and grilled, the fat is drained and you’re not burying them under cheese, bacon and high-fructose ketchup and then packing them into a bun the size of a catcher’s mitt.

Chicken is a separate issue. In my mind, there is nothing that better captures where we have gone wrong as a food culture than the countless fried-chicken fast-food outlets that dot highways. Fried chicken is consumed literally in buckets–and that’s got to be a bad sign. What’s more, even at home, frying chicken wrecks the nutritional quality of the meat.

Indeed, chicken is so lean and tasty it can actually redeem a lot of foods that are otherwise dietary bad news. I don’t have a problem with tacos, for example, if you do them right. A chicken taco is a better option than beef, and a fish taco is the best choice of all. All the raw ingredients are available in supermarkets, and what you make at home will be much healthier than what you get when you go out.

There’s even goodness to be found in some of the supermarket’s seemingly most down-market fish and meats: those sold in cans. One great advantage to canning is that it does not affect protein content, making such foods as canned tuna, salmon and chicken excellent sources of nutrition. Canned salmon in particular is as nourishing as if you caught a fresh salmon that afternoon. It’s also easy to prepare: you can put it on a salad or serve it with vegetables and have dinner ready in minutes.

Let’s also take a moment to celebrate the tuna-salad sandwich, which is to lunch what the ’57 Chevy is to cars–basic and brilliant. Sure, there are ways to mess it up, with heaping mounds of mayonnaise and foot-long hoagie rolls. But tuna is loaded with niacin, selenium, vitamin B12 and omega-3 fatty acids, and a sandwich done lean and right, on whole-wheat bread with lettuce and tomatoes, is comfort food at its finest with little nutritional blowback.

Still, some of these cans are land mines. Plenty of products include flavor enhancers such as sugar, salt and MSG. And there are canned meats that really are nothing but bad news. Vienna sausage is the type of food that keeps us heart surgeons in business. As for hot dogs and luncheon meats like salami and bologna, just don’t go there. They’re way too high in nitrites and sodium to do you even a bit of good.

Guilty Pleasures

To me, ice cream is a sacred food. When I was a boy, my father would drive me to the local ice cream store on Sundays. We would spend the half-hour car ride talking, and I got to know my dad better through these conversations. It wasn’t really about the ice cream; it was about time spent together. I even made the decision to become a doctor in that very ice cream store–something, perhaps, about the sense of well-being I was experiencing. I have used ice cream as a family focal point with my own children, and to this day it is an indicator of an occasion. Ice cream should be in your life too. What’s more, it’s not even a bad or unhealthy food.

For starters, the protein and calcium in ice cream are great. And some of the ingredients in better ice creams are good for you too, including eggs (yes, eggs, a terrific source of protein and B vitamins and perfectly O.K. if your cholesterol is in check) and tree nuts such as walnuts, almonds, cashews and pistachios. As with most other foods, the problem is often the amount consumed. A serving size is typically half a cup, but that’s a rule that’s almost always flouted, which is a shame. Overdoing ice cream not only takes its toll on your health but also makes the special commonplace. I often say that no food is so bad for you that you can’t have it once–or occasionally.

Peanut butter has none of the enchanted power of ice cream. It’s a workaday food, a lunch-box food–and an irresistibly delicious food. The allegedly pedestrian nature of the supermarket is perfectly captured in the mainstream, brand-name, decidedly nongourmet peanut butters lining the shelves. But here again, what you’re often seeing is a source of quality nutrition disguised as indulgent junk.

Peanut butter does have saturated fat, but 80% of its total fats are unsaturated. That’s as good as olive oil. It’s also high in fiber and potassium. But many brands stuff in salt and sweeteners as flavoring agents, so read the labels. Sometimes supermarket brands turn out to be the best.

And guess what? Preserves and jams without added sugar can be great sources of dietary fiber, vitamin A, vitamin C and potassium, and whole-wheat bread is high in fiber, selenium, manganese and more. So by shopping right and being careful with portions, we have fully redeemed that great, guilty American staple: the PB&J.

Snack foods are a different kind of peril, but if there’s one thing Americans have gotten right, it’s our surpassing love of salsa. Year after year it ranks near the top of our favorite snack foods, especially during football season. I think salsa is a spectacular food because it’s almost always made of nothing more than tomatoes, onions and cilantro and usually has no preservatives. And remember, those tomatoes contain lycopene, a powerful antioxidant that helps battle disease and inflammation.

Another great south-of-the-border staple is guacamole. Its principal ingredient is, of course, avocados, which are loaded with the happiest of fats: the unsaturated kind that help prevent heart disease. They are also rich in vitamin K (over 50% of your recommended daily intake from just half an avocado) and vitamin C. But keep portions in check to hold the line on both calories and sodium.

Finding something to scoop up those dips is a problem. Tortilla chips fried in lard and covered with salt are simply not a good idea. Baked pita chips (ideally unsalted) are great, but there’s no way around the fact that they’re pricier than tortilla, potato and corn chips.

The Beauty of Simplicity

Pretty much any aisle in any supermarket has foods that you might think mark you as a culinary primitive but are worth considering. Pickles? Sure, they’re loaded with salt, so read labels and exercise care, but they’re high in vitamin K and low in calories, and the vinegar in them can improve insulin sensitivity. Baked beans? Pass up the ones cooked with bacon or excessive sweetening, but otherwise, they’re a great source of protein and fiber.

Meanwhile, the condiments section has mustard–extremely low in calories, high in selenium and available in a zillion different varieties, so you’ll never get bored. Popcorn? Absolutely, but go for the air-popped, stove-top variety instead of the microwavable kind covered in oils and artificial butter flavorings. And chocolate! Ah, chocolate. Stick with dark–65% cocoa–and don’t overdo the portions. I know, that’s not easy, but do it right and you’ll get all the antioxidant benefits of flavonols without all the calories and fat.

Throughout the developed world, we are at a point in our evolution at which famine, which essentially governed the rise and fall of civilizations throughout history, is no longer an acute threat. And we know more about the connection between food and health than ever before–down to the molecular level, actually.

This has provided us the curious luxury of being fussy, even snooty, about what we eat, considering some foods, well, below our station. That’s silly. Food isn’t about cachet. It’s about nourishment, pleasure and the profound well-being that comes from the way meals draw us together.

Even foods that I have described as no-go items are really O.K. in the right situations. I recently enjoyed some fantastic barbecue after a long project in Kansas City, Mo., and I certainly ate the cake and more at my daughter’s wedding. As with any relationship that flourishes, respect is at the core of how you get along with food–respect and keeping things simple.

Mehmet Oz is a vice chairman and professor of surgery at Columbia University, a best-selling author and the Emmy Award–winning host of The Dr. Oz Show

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com