The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 107,477 drug-related deaths occurred from August 2021 to August 2022, with the majority attributed to the potent synthetic opioid, fentanyl. These provisional estimates reflect a modest (2.57%) decrease from the previous year, defying an increasing trend that has persisted for the last 20 years where opioids have been the primary driver of overdose deaths. Through its evolutions, the current opioid epidemic has proven to be an ever-moving target, and there’s much we still need to learn in order to curb fentanyl exposure and overdose.

The origins of the current opioid epidemic are now well known. In the early 90s, the liberal prescribing of opioid analgesics led to widespread availability and diversion of opioids like oxycodone. Some of those exposed to prescription opioids developed opioid abuse and dependence, which we now refer to as opioid use disorder. Many of those affected began with prescription opioids later transitioned to heroin, which was cheaper and increasing in purity.

Accordingly, in 2010, we began to see a rise in heroin-related overdose deaths. The steepening climb in opioid overdose death rates, along with the increasing mortality gap among white, working-class Americans, put opioid use disorder at the forefront of the national agenda. Billions in treatment and research funding were allocated to combating the epidemic, and compassion for people with opioid use disorder was at an all-time high. However, the epidemic evolved again when the opioid market was inundated with illicitly manufactured fentanyl and its analogs. This transition has had an impact upon key stakeholders in the opioid epidemic: people who use opioids, treatment providers, researchers, and harm reduction practitioners.

In 2008, I began post-doctoral training at Columbia University Medical Center in New York and have watched the evolution of the opioid epidemic as a behavioral pharmacologist and burgeoning harm reductionist. With fentanyl increasingly becoming the opioid of choice and unavoidable for many people who use opioids, it’s clear that it has presented unique challenges to reducing the harms of opioid use disorder.

When asked why fentanyl is so problematic, the obvious answer is its potency. Fentanyl is generally estimated to be 50 times more potent than heroin, and some analogs, like carfentanil, can be thousands of times more potent than heroin. With opioids, their “addictive” effects are pharmacologically entwined with their overdose risk. This means that greater substance-induced euphoria and anxiolytic effects are accompanied by greater respiratory depression (the primary means by which opioid overdose is fatal).

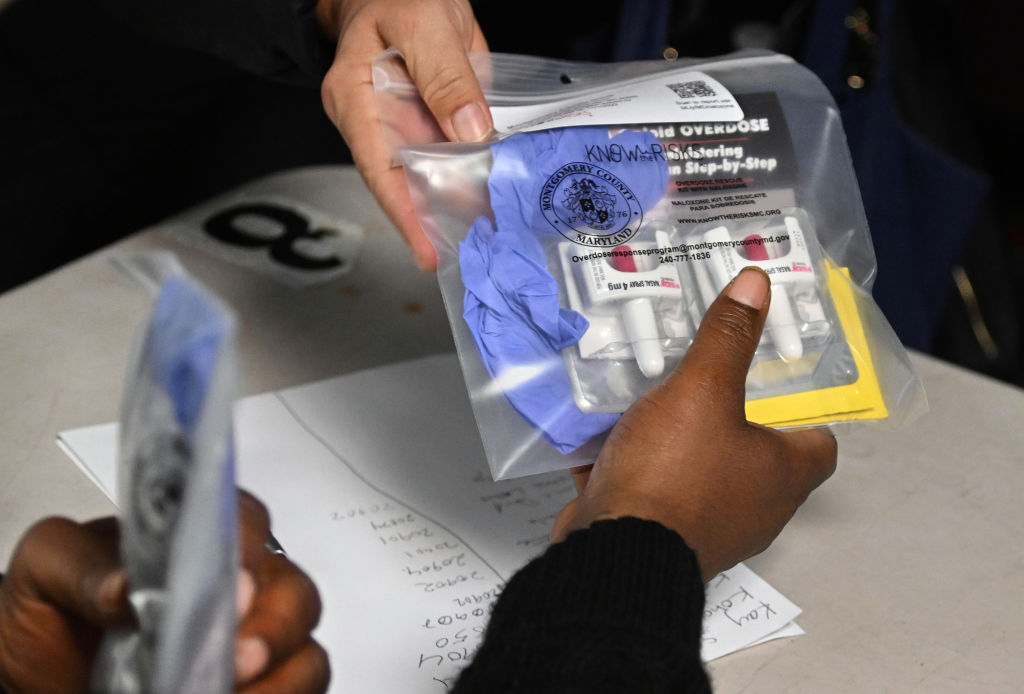

Early in the overdose epidemic, there was a growing implementation of programs that sought to equip anyone who may encounter an opioid overdose with the opioid antagonist: naloxone. Though naloxone can block fentanyl’s effects, there is evidence to suggest that there is less time to save someone from a fentanyl-related overdose, in comparison to other opioids. Fentanyl’s potency has led some naloxone distribution programs to modify practices, giving more than the standard two doses of naloxone. It also fuels an ongoing debate about the need for and risks of higher-dose formulations of naloxone. Some argue that higher dose formulations of naloxone would be better at treating fentanyl-related overdoses. While others worry that the fear of naloxone-precipitated opioid withdrawal will reduce the likelihood that these formulations will be used, even in potentially life-saving situations. Finally, fentanyls are known to have adverse effects uncommon to other opioids. Chest wall rigidity—known as “wooden chest syndrome”—may contribute to fentanyl-induced effects on breathing and is not likely to respond to naloxone.

Read More: Over-The-Counter Narcan is a Great First Step, But There’s Still Work to Be Done

In addition to increasing the risk of overdose, fentanyl has had other consequences for people who use substances. Over the last five to 10 years, we’ve seen illicitly manufactured fentanyl used more and more to increase the potency of heroin. This began in the east coast drug markets of the U.S. and is heading west. In N.Y., fentanyl has largely replaced heroin in the illicit opioid market and is no longer a cutting agent, but rather the chief constituent. Early in the fentanyl epidemic, heroin users often expressed fear and took steps to avoid heroin cut with fentanyl. Harm-reduction practitioners attempted to support such efforts by supplying fentanyl test strips to allow users to test their supply. However, the prevalence of fentanyl in many illicit markets now makes it impossible to avoid.

For opioid users, the resulting transition to physiological dependence on fentanyl has presented other challenges. Though more potent, fentanyl is shorter-acting than opioids like heroin and oxycodone, which means that people typically have to use it more frequently throughout the day to avoid withdrawal. In addition to the greater financial burden, taking fentanyl on more occasions makes it more challenging to always use sterile equipment, increasing the risk of exposure to blood-borne pathogens such as HIV and hepatitis C. The short-acting nature of fentanyl is also thought to be responsible for the rise in the use of the adulterant xylazine. Xylazine is an animal anesthetic, thought to be cut into the fentanyl supply to prolong its effects. Being a sedative, xylazine may increase the risk or severity of an opioid overdose event. The presence of xylazine in the illicit opioid supply has been associated with an increase in severe wounds, some of which are extra-local, meaning they appear at places on the body other than the injection site. More research is needed to establish a causal connection between xylazine adulteration and these wounds, which could be used to develop xylazine-specific harm-reduction recommendations.

The use of buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid use disorder, has also been impacted by the omnipresence of fentanyl. Fentanyl’s unique pharmacology as lead prescribers to develop new ways to transition fentanyl-dependent patients onto buprenorphine. Though fentanyl is short-acting, it is highly lipophilic, resulting in prolonged dissipation from the body. Thus, there is much to learn concerning fentanyl’s withdrawal profile (i.e., severity and duration) as it is not consistent with its pharmacodynamic effects. Clinical researchers are also struggling with the challenges of fentanyl dependence, as withdrawal management and opioid-maintenance protocols, which had been used in clinical trials for years, no longer being effective.

Illicitly manufactured fentanyl is also increasingly being adulterated into counterfeit pills being sold online as prescription opioids or benzodiazepines. This may be contributing to increased rates of opioid-related overdose among recreational users, particularly younger adults who experiment with these substances.

Finally, there is growing concern that the fear of fentanyl is causing us to revisit a dangerous legislative path. Some states, like Oklahoma, are developing criminal penalties associated with fentanyl which are reminiscent of the draconian crack-cocaine sentencing laws. Mandatory life sentences and murder charges have been touted as ways to combat the distribution of fentanyl. Legislation of this type is unlikely to change the composition of the illicit substance supply and will do nothing to reduce the demand for opioids. Though frustration with the persistence of the opioid epidemic and the dangers of fentanyl is understandable, we should move forward with scientifically supported methods to reduce the prevalence of substance use disorders and minimize overdose risk.

In Europe, mobile drug-checking services at raves allowed party-goers to know what they were using. Practices like this can help ensure a safer drug supply and may help reduce overdose risk among younger or “recreational” users. Safe consumption facilities also provide a means to reduce overdose risk among active users, along with increasing access to naloxone. In fact, in March 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first the over-the-counter naloxone formulation, Narcan. For those who are seeking treatment, our current FDA-approved medications remain the best way to mitigate the morbidity and mortality associated with opioid use disorder. Furthermore, researchers are developing novel treatment approaches such as opioid vaccines and other immunotherapies.

There is a need for more empirical research on several aspects related to the fentanyl epidemic, and many dedicated individuals are working towards getting the answers necessary to address this problem. But it’s a long road ahead, and with that in mind, we must also look forward, beyond fentanyl. Epidemics of addiction can be cyclical in nature, and what we learn in our fight against fentanyl can help prepare us for what’s next.

If you or someone you know may have a substance use disorder, SAMHSA’s National Helpline (1-800 622-4357) is a free and confidential, treatment, referral, and information service.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com