Rising out of Copenhagen’s harbor, visible only as a line of rocks peeking through the blue-gray waves, is one of Europe’s most controversial climate projects. Lynetteholm, a one square mile artificial island, is being built to shield the low-lying Danish capital from storm surges, which are intensifying as sea levels rise. Politicians approved the project in 2021, promising a world-leading bounty of benefits, from flood protection, to new housing, to cash for other city upgrades.

But ever since then, climate activists, scientists, and city residents have been on a mission to stop Lynetteholm. (It’s pronounced something like “Lunetta-holm.”) They say authorities are ignoring the damage Denmark’s largest ever construction project could do to the local environment, and the carbon pollution it will create. Now, a new front in that battle is opening up—thanks to some very specific geography.

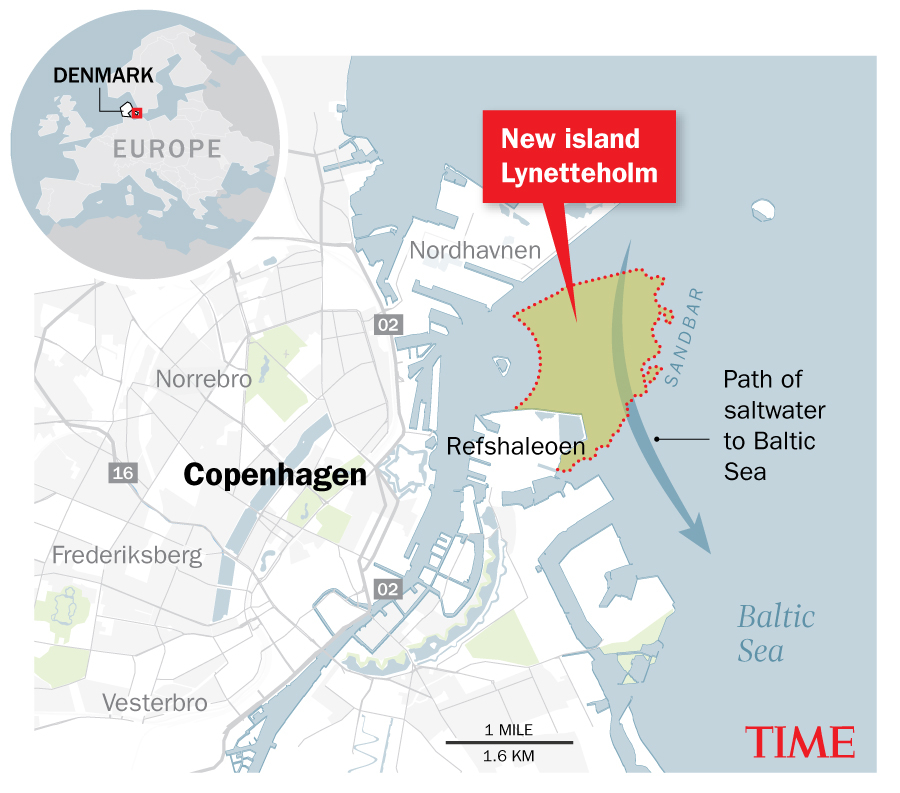

Lynetteholm is being built in the Øresund, a relatively narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Baltic Sea, via the North Sea. Earlier this month, a group of independent scientists advising Denmark’s government warned that the island’s construction has already blocked one of three undersea trenches through which Atlantic salt water flows into the Baltic. Unless that is reversed and the project scaled back, the scientists say, Lynetteholm could end up desalinating the sea—which Denmark shares with eight other countries—with unknown ecological consequences. On Wednesday, the Danish Climate Movement, an association of campaign groups, filed for an injunction against Lynetteholm, asking a court to halt construction until the desalination concerns have been resolved.

Not everyone agrees that Lynetteholm poses such a threat. An earlier assessment carried out by the Danish Hydraulic Institute found that the effect on the Baltic would be minor. By&Havn, the publicly owned development company building Lynetteholm, says the matter has already been resolved to the satisfaction of Sweden, Denmark’s closest neighbor.

But climate activists hope the salinity issue could derail the project. If granted, the injunction would buy time for another lawsuit over Lynetteholm to work its way through the courts, says Frederik Sandby, the Danish Climate Movement’s general secretary. The group sued the Transport Ministry, which shares responsibility for Lynetteholm with Copenhagen’s city government, in 2021, arguing that the project was rushed through without properly accounting for its environmental impact or Denmark’s climate goals.

A global island-building push

Lynetteholm is part of a global trend in land reclamation that is unnerving environmentalists. According to a study published in February by a group of international researchers, between 2000 and 2020 coastal cities filled in wetlands and shallow seas to create more than 625,000 acres of new land and ports around the world. That’s around 43 new Manhattans.

Land reclamation is increasingly touted as a climate solution. In the Maldives, the government is championing an island-building campaign to replace the land it is losing to fast-rising seas. In Nigeria, the finishing touches are now being made to Eko Atlantic, a 10 square-mile reclaimed neighborhood shielding Lagos from erosion. Former Lagos state governor, now Nigeria’s president-elect, boasts that the project “tamed the Atlantic Ocean.”

But scientists warn that such projects are speeding ahead without weighing the risks of meddling in fragile coastal ecosystems. People living near reclaimed land schemes have reported grave unintended consequences, not only for marine life—as is the fear in Copenhagen—but also for the livelihoods of fishermen, and patterns of coastal erosion, which can get worse at nearby places that are not protected by the new islands’ well-resourced engineers.

Critics claim it is profit, rather than climate concern, that is driving the current frenzy of island-building. While humans, including the Danes, have always raised land from the seas for settlement and defensive purposes, the February study identifies growing demand for “luxury” waterfront real estate as “the catalyst” for a new “urban transformation” unfolding on the world’s coasts. Lynetteholm is expected to get approval for the construction of 35,000 homes by 2070, and the island’s opponents say it was the opportunity to sell those high-value plots to developers that convinced politicians to back the island over less controversial flood measures. “The Lynetteholm project is bizarre yet typical of the current age in which [land reclamation projects are legitimized as climate solutions],” says Sarah Moser, an associate professor in the geography department at McGill University. “Massive real estate schemes get to claim hero status.”

The Lynetteholm case is a crucial junction for the land reclamation trend, says Sandby, the climate activist. “The world is at this moment of figuring out if artificial islands are sustainable or not.” Denmark and Copnhagen, he points out, are often held up as climate leaders because of their extremely ambitious emissions targets. “If we do these things, and it’s looked upon as beneficial, as part of the way Denmark builds sustainably, then that’s a huge mistake.”

Preparing for a “massive rise” in floods

No one disputes that Copenhagen needs to do something to prepare for rising seas. The city sits on two fairly flat islands, one of them just a few feet above sea level, and is surrounded by water on three sides. The last really severe storm surge to affect Copenhagen was way back in 1872, when winds over the Baltic pushed a wall of water inland over the city, destroying thousands of homes. Such an event will become increasingly likely over the next few decades. Officials say the height of the average surge will quadruple to 1.3 feet by 2050, and a “massive rise” in the number of storm-triggered floods is expected around 2070. Before Lynetteholm, Copenhagen was planning a more traditional set of dikes in front of its harbor—the solution climate activists still prefer.

But Lynetteholm will work better than a dike, says Anne Skovbro, the CEO of developer By&Havn. Firstly, it’s adaptable. If sea levels rise faster than expected over the next few decades, the wide expanse of soil can easily be beefed up to sit taller. Second, it won’t disrupt Copenhagen’s view of the water. Third, it will use up waste. Some 80 million metric tons of debris generated by other construction sites in Copenhagen over the next thirty years will be poured into the already-built stone perimeter in the Øresund to create the island.

And Lynetteholm should, if all goes well, be self-financing, with payments for the disposal of waste soil from other construction projects covering the cost of Copenhagen’s flood protection. So far, officials have only approved the island-building phase of the project. But it is widely expected to get authorization to build 35,000 homes by 2070, in which case the proceeds of land sales would also create cash for the government—helping to fund other infrastructure projects. “It’s the only solution for climate adaptation where the taxpayer doesn’t have to pay,” Skovbro says.

What’s salt got to do with it?

But opposition has been unrelenting. Environmental lawyers have condemned the environmental impact report used by politicians in their decision-making process on the project. The document only factors in the island itself, not the homes, subway, and highway that may one day sit on top, but which have not yet been officially approved. One lawyer dubbed the report “a freehand drawing” for its lack of detail. Urban planners, meanwhile, say the planned highway, sold as a way to relieve congestion in the rest of the city, will induce more demand for cars, and therefore more traffic, in the long run.

Climate activists point to the project’s carbon footprint: between 2023 and 2055, Lynetteholm will generate 242,920 metric tons of CO2, per By&Havn’s predictions. To be fair, that’s only the amount generated by about 48,000 Danes—or 0.7% of the population—in a single year. But Sandby argues that the project is an unnecessary use of the world’s carbon budget, and doesn’t align with the urgency with which Denmark claims to view emissions reduction: “In the situation that we’re in with the climate crisis, we cannot afford to build in such a way.”

Over the last two years, residents have also staged several street protests over feared disruption to bike-centric Copenhagen by hundreds of heavy trucks carrying debris to the harbor each day. (By&Havn claims that there will be no increase in traffic, as Copenhagen’s construction debris is typically already transported to an existing depot in the harbor area.) Lynetteholm’s plans to dispose of contaminated waste released from the seafloor by construction have also fueled concern. Last year, amid public backlash, politicians were forced to convene an expert panel to advise the Transport Ministry on that issue.

That brings us to the latest dispute: the Kongedybet trench (‘The King’s Deep’, in English.) Stiig Markager, a member of the expert panel and a professor of marine ecosystems at Denmark’s Aarhus University, says the trench plays an important role in delivering salt into the Baltic sea. Because salt water is heavier than the Baltic’s brackish water, it flows south through the deep trench, while brackish water flows above it into the North Sea. Lynetteholm’s stone perimeter has now cut off that exchange. “The blockage could potentially have a significant impact on the environment in the Baltic Sea,” Markager says.

By&Havn says the desalination issue has already been looked at by two organizations, the Danish Hydraulic Institute, and Deltares, a Dutch research company, who agreed that it would likely reduce the amount of salt water flowing into the Baltic by 0.25% each year.

While that may not sound like much, Markager argues that those previous assessments were “very superficial,” modeling the blockage’s impact on the trench only in comparison to a single year, 2018; a “scientifically sound” model would need to consider flow patterns over decades at the very least. The compound effect, he says, would drastically reduce salinity in the Baltic over the next century. That would endanger fish and plants in the Baltic that have adapted to the sheltered sea’s unique semi-salty water, and fuel toxic algae blooms. A coalition of seventeen European conservation organizations raised similar concerns last year.

Markager says construction should be paused to further investigate what will happen to the Baltic. Or, he says, the peninsula could simply be scaled back by around a third, so that it wouldn’t block the trench.

A rising tide of coastal conflict

Skovbro says Lynetteholm’s environmental critics are refusing to look at the positive sides of the project. Using the surplus soil in Copenhagen will mean fewer trucks burning fuel to transfer it elsewhere in Denmark, for example, and By&Havn has established a partnership with Danish car manufacturers to help drive the creation of electric trucks big enough to transport the materials. The project is also using waste from a rail-building scheme in Norway.

“The reality is that we need to protect Copenhagen from flooding, and a lot of the issues that people are worried about will be issues no matter how we do it,” she says. “We have quite a high level of environmental standards in general.” In that sense, she adds, the project could serve as an “example” to other land reclamation projects around the world.

That’s exactly what Sandby is afraid of. The Climate Movement wants to use its campaign against Lynettehold to set a precedent that will weigh on politicians mulling future carbon intensive infrastructure in Denmark, and governments considering artificial island projects around the world.

Whoever you agree with, the conflict on our coasts is likely just getting started. Skovbro points out that almost every part of Denmark, not to mention the rest of the world’s low-lying countries, will likely need to launch serious flood protection programs in the coming years. They will face similar dilemmas as Copenhagen. “We are just the first big project doing it here,” she says. “A lot of these projects will probably have challenges, because it is very difficult to balance all of this.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Ciara Nugent at ciara.nugent@time.com