A study covering almost 300 carbon offset projects found that the industry’s top registries have consistently allowed developers to claim far more climate-saving benefits than justified.

Researchers led by Barbara Haya from the University of Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy assessed the methods underpinning forestry projects responsible for 11% of all carbon offsets ever issued. They found shortcomings in each that resulted in bogus credits.

“Across the board, they fall far short from good practice in carbon accounting,” Haya said. “It’s pervasive.” The study, the first of its type, was published Tuesday in the journal Frontiers in Forests and Global Change.

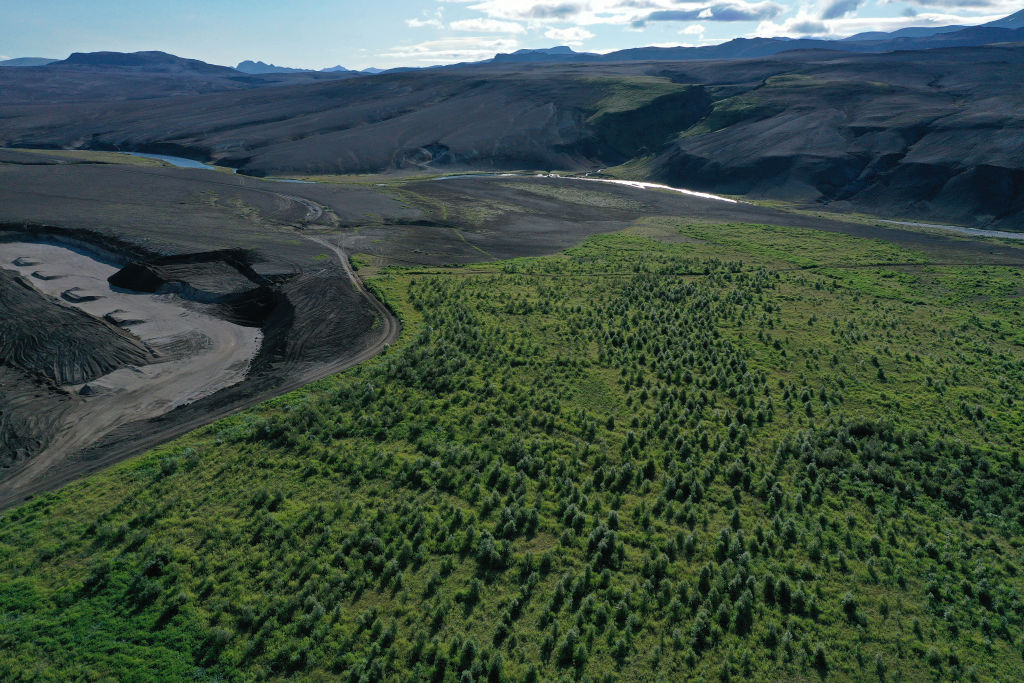

Haya and her team looked at the methods applied to projects that sought to improve forest management — one of the most popular sources of offsets on the market. In theory, this might involve waiting to harvest trees when they’re older, limiting the number of trees that can be cut per hectare, or minimizing the environmental impact of logging infrastructure such as roads. In reality, the researchers found, project developers were often able to generate credits even when no changes were made.

In the unregulated carbon offsets market, standards are upheld by a handful of groups that host their own registries. The organizations generate revenue by issuing credits, a business model that incentivizes leniency over conservativeness. And if one body tightens its standards, a developer can just go to another. The system is structured to maximize entry for projects that seek to mitigate climate change. But without higher standards and stricter oversight, it’s in fact fueling a race to the bottom, Haya said.

The bulk of credits generated using the approaches Haya’s team studied came from Verra’s Verified Carbon Standard, Winrock International’s American Carbon Registry and the Climate Action Reserve. The three registries, among the world’s biggest, also host credits for the California Air Resources Board, which itself sets standards for credits that can be used under the state’s regulated emissions scheme.

All four groups stood by their approaches, which they said had undergone scientific reviews and incorporated feedback from experts and the public. A spokesperson for the California Air Resources Board said its methods have been upheld in court.

Haya’s team found that the registries’ methods failed to uphold basic criteria that would ensure projects make a real difference to carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. That includes ensuring their carbon credits funded tree-protecting activities that wouldn’t have otherwise happened, and making a reasonable baseline assessment of that alternate future. Developers also have to address if they are displacing harmful activities elsewhere and should account for risks such as wildfires.

For example, the researchers found that most of the credits of the type they studied had been generated against a baseline of aggressive harvesting practices that didn’t align with past practices in the area. That meant developers could be credited for operating as usual, rather than for improvement.

The shortcomings show that companies can’t rely on offsets generated using these methods to make claims of carbon neutrality or climate advances, Haya said. Any that are doing so are portraying a misleading sense of progress. “It makes the global community think that we’re doing more than we’re really doing at this brief moment we have to dramatically reduce our emissions to prevent runaway climate change.”

Haya said her team’s findings amount to a systemic failing in the market. The challenge of placing a precise number on how much carbon is saved to generate each offset sold impacts all projects, not just forest management. Last year, a Bloomberg investigation found that almost 40% of the offsets purchased in 2021 came from renewable energy projects that didn’t actually avoid emissions.

Haya and her team have suggestions for improvement that include using dynamic rather than static baselines which would adjust to market conditions over time. Verra said it recently introduced a new methodology adopting this approach. But ultimately Haya, whose been studying the offsets market for over two decades, has been left feeling jaded.

“Offsetting is a misnomer — you can’t ‘offset’ your emissions,” she said. “We need alternative ways of supporting climate mitigation because the current offset market is deeply not working.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com