I am in Kyiv. In the heart of a city whose superhuman efforts allow life to go on. Friends and comrades are organizing, in secret, at the Zhovten, the most beautiful movie theater of the Podil quarter, the Ukrainian premiere of my film, Slava Ukraini. And, from Tbilisi, Georgia, on the far shore of the Black Sea, more than 1,500 kilometers away, a handwritten letter reaches me, in a trembling script, from Mikheil Saakashvili.

Saakashvili… Like a ghost rising from a recent past (2008!) that seems suddenly so far away… It was springtime. The winds of liberty blew over the Georgia where he was president. It was a wind of liberty and roses. I am there. I see, braving the Russian tanks on the doorstep of the capital, this gentle giant who, like the heroes of literature for children, has a princess to save, named either Georgia or Europe, no difference. He resists. Calls for aid. Seems, at times, poised for victory. Loses the election. Goes into exile in Ukraine, where he becomes governor of Odesa Oblast. Returns home. And finds himself thrown into jail by a power under orders from Putin who, not content to just put him away, seems to have poisoned him as well.

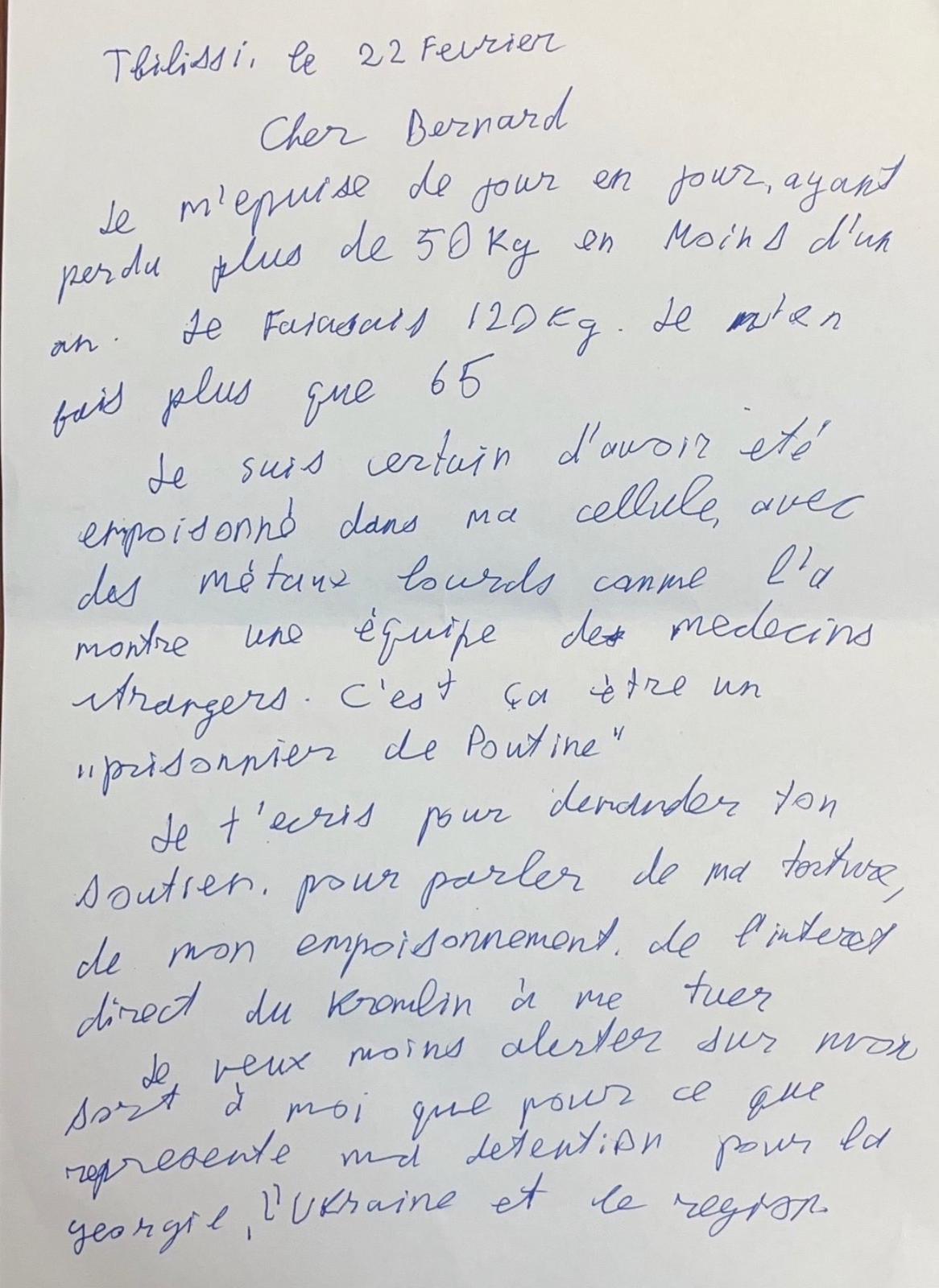

“Dear Bernard,” he writes, now, on a sheet of thin paper which makes me shiver to read again… I was “poisoned in my cell”… A “team of foreign doctors” found under my nails, in my blood, “traces of heavy metals”… “Day by day I get weaker”… I’ve lost “at least 50 kilos in less than a year”… I write to you to “ask for your support” and to beg you to “speak of my torture, my poisoning, and of the Kremlin’s direct interest in killing me”… I write to you because you came to Georgia in 2008, in the era when Putin was testing the new Iron Curtain he wishes to draw today across Ukraine. And I write so you tell the world that “my death in prison” will mean my country “is thrown into the arms of Russia” and that, beyond my borders, as Minister Lavrov’s spokesperson has sworn, my fate “also awaits Zelensky”…

I try to imagine him, this exultant, magnificent character, out of proportion in all ways, not just physically. I try to recall his verve, his gaiety, his faith in the democratic transition and in a tomorrow that sings liberty. I try to picture him, thin, boney, frail, perhaps dying. Has he lost his Rabelaisian exuberance? His jovial enthusiasm, like that of a Porthosian musketeer? What is left of his heroic intelligence, his hardiness, his confidence in the genius of those who he held as masters, the great spirits of French humanism whose language he speaks impeccably?

I try to imagine how, exactly, he wrote these words that I am looking at, and through what twisting paths he managed to get them to me. I imagine a prison visiting booth. Or, as in The Three Musketeers again or the era of Soviet dissidents, an envelope passed in secret, a sympathetic or complacent jailer, a bottle at sea, a samizdat. Did he write them at a table, these lines in a childish hand, clumsy but perfect for expressing his suffering through it? On a thin mattress where he has grown too weak to get up? Or from the ground itself, like Solzhenitsyn in the Gulag? He was a European great and, even fallen, remains so. This brave man, hated by Putin’s little grey men like few others, has lost none of his panache.

I also try to imagine, and to understand, how he could have decided, 17 months ago now, to jump back into the lion’s den, defying the inevitable. Like Navalny, deep down. Like other heroes of the new dissidence. Like Khodorkovsky, the former oligarch once imprisoned by Putin, now become one of the faces of free Russia—Saakashvili also, it seems to me, knew the fate that awaited him and chose to face it. Are these men helpless before the unbendable will of the Kremlin terrorist? Is Micha despairing before the versatility of his nation, which loved him before chasing him out? Is there a moment when the idea strikes you, as brazen as may be your soul, that it’s time to join the immortal race of men of good faith who spared no effort in search of the triumph of a just and lost cause?

Micha, I don’t know if you’ll read, from your jail cell, or from the hospital where they recently put you, these words that I write in reply to yours, thinking of you and the likely peril of your tortured body. I don’t even know if, from where you are, you hear the murmur rising from the Rustavili avenue where, at the hour I write this, thousands of pro-European protesters are demonstrating and chanting the Ukrainian anthem. But I know that Europe, your country, does not seem to hear your warnings. I know that, in this West that you championed, you, and your brave outraged and revolted people, receive only a glacial silence. How can we not be ashamed of that, when we speak the language of Hemingway or Chateaubriand? Of Zorro or Alexis de Tocqueville? How can we not—remembering Sartre and Camus who you claimed once to be the equal of—be horrified by the disillusioned negligence of western opinions?

A dying man cries out for help. A whole people braves the militias in the pay of Putin, by taking on, ten years later and, I repeat, 1,500 kilometers away, the Ukrainian spirit of the Maidan. And the world (if this still means something more than a mob controlled by the algorithms of nothingness) could care less. They don’t give a fuck, as one says, in the newspeak slang, to express servility to evil. This is unbearable.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com