Russia’s unjustifiable, brutal assault against Ukraine is an unusually black and white geopolitical situation—we all know who the bad guy is—and yet the climate consequences of Russia’s invasion are mixed. Russia remains important to the global energy transition, both in spite of itself and in defiance of the West’s effort to sanction it out of energy markets.

Putin used oil and gas to strangle Europe and trigger a global energy crisis in 2021-2022, both in advance of the invasion of Ukraine and since. In the immediate term, this caused a spike in coal use for heating and power and an ensuing increase in greenhouse gas emissions in many parts of the world. But in the medium to long run, Putin’s energy crisis has dramatically accelerated the energy transition away from legacy fossil fuels. The International Energy Agency now believes fossil fuel use globally will peak within a decade.

Europe’s emergency pivot away from Russian natural gas not only reduced its share in the continent’s energy mix from 40% in 2021 to 7.5% by the end of 2022, alongside drops in Russian oil imports, but also spurred frantic investment in renewables and nuclear power. The continent’s solar capacity almost doubled in 2022, and wind and solar together produced more electricity (22%) than natural gas in 2022 for the first time in Europe’s history. Nuclear is meanwhile enjoying the beginnings of a renaissance, with Poland, Estonia, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, the U.K., and many others planning new nuclear plant construction with urgency. Sales of heat pumps, which make heating with electricity instead of by burning fuels, jumped by 35% across Europe in 2022. Even Germany, so deeply dependent on Russian gas a year ago, is now on pace to eliminate fossil fuels by 2045. Berlin is also reevaluating its post-Fukushima hostility to nuclear.

In effect, what Russia weaponizing hydrocarbons accomplished was a shift to clean power and heat decades ahead of expectations. But the awkward reality is that Russia was and still is too large an energy powerhouse for it to be immediately and completely excised from global energy markets. This is just as true of a transitioned, clean global energy sector as it was of fossil fuels. However frustrating, Russia is still one of the world’s major energy superpowers despite sanctions, price caps, market shifts, and new renewables investment.

In fact, multiple rounds of sanctions packages imposed on Russia by the West carefully avoided cutting of energy exports until many months into Putin’s war against Ukraine because Russian energy was simply too important for markets to give up quickly. The world, and Europe in particular, was not ready to do without Russian oil, gas, diesel, coal, uranium, and more. Europe’s ability to break free of Russia’s energy dominance has, counterintuitively, relied on buying both Russian liquified natural gas (LNG) and non-Russian LNG that was originally headed to Asia but rerouted when Russian gas supplies turned eastward instead of westward.

Read More: Climate Change Saved Europe From Putin this Winter

Following the February 24, 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the first energy strike was the U.S.’ mostly symbolic March 8 embargo on Russian energy commodities. Poland sanctioned Gazprom, Russia’s natural gas giant, on April 26, but the EU didn’t apply hard restrictions against Russian energy exports until its December 5 imposition of the $60 per barrel price cap on Russian crude oil. Effective February 5, 2023, the E.U. stopped imports of Russian oil products, principally diesel. For natural gas, Russia forced the issue, cutting off almost all pipeline exports to Europe by August 31, 2022. Europe increased its imports of Russian LNG and coal, but overall the continent is now mostly weaned off its aggressive eastern neighbor’s energy exports.

This hard fought freedom has coupled with the surge in renewables investment to achieve what political will had not—the energy transition. The uncomfortable irony is, however, that Russia is still essential to that very same transition. The largest country in the world by land mass, Russia is dominant in one area absolutely critical to powering the world without carbon emissions—nuclear generation—and it is also an important supplier of the minerals necessary to achieve decarbonization at scale.

Experts generally agree that reaching carbon neutrality—“net-zero”—in industry, transport, heating, and so on, depends principally on electrification. The world’s reliance on electricity is set to explode as we phase out fossil fuels in heating and transport, among other sectors, and replace it with electricity powered cars, heating, and more.

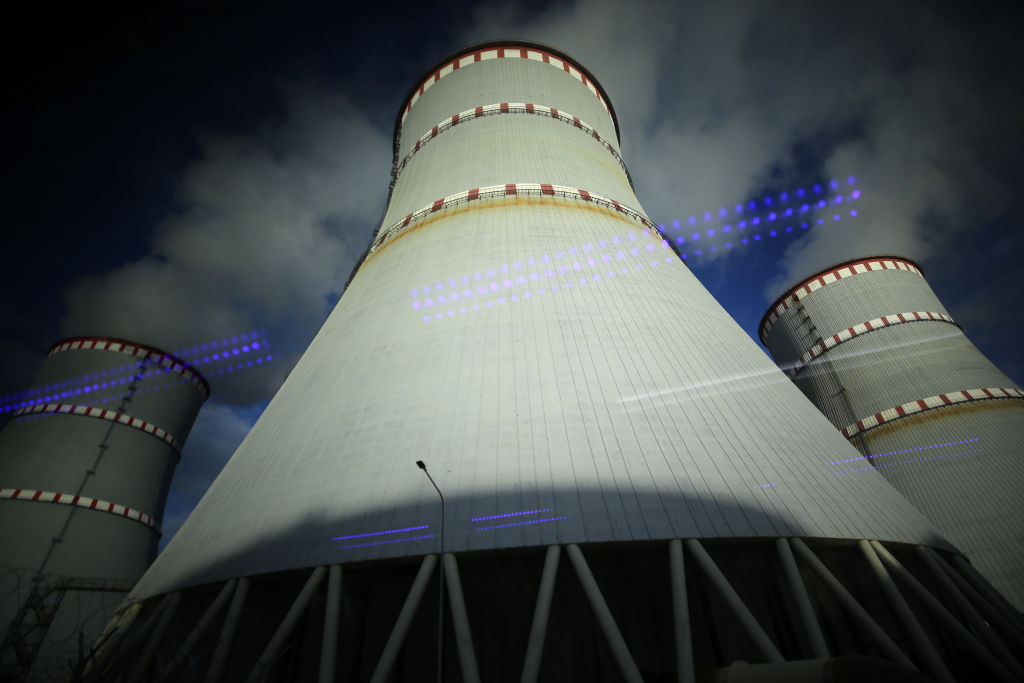

Nuclear power is the only electricity generation technology that can reasonably satisfy the voracious energy demands of an ever growing world while also not contributing to climate change. There are approximately 440 nuclear reactors operating now, spread across 32 countries and Taiwan. That makes for about 390 gigawatts of electricity, roughly 10% of global demand. Sixty new reactors are currently under construction, mostly in Russia and China, and also India. Another 100 are formally in planning stages, with 300 more under discussion. While much of the activity is in countries with existing nuclear programs, dozens of new ones are jumping in.

This nuclear renaissance depends on uranium. Russia has 8% of known deposits. That may not seem like enough of a share to make for market dominance when Australia and Kazakhstan together have 43%, but Russia also has 40% of the world’s uranium conversion capacity and 46% of global enrichment capacity. In 2021, the U.S. bought 14% of its uranium from Russia and used Russian enrichment services for 28% of its needs. For Europe, 20% of its uranium and 26% of enrichment comes from Russia. Most immediately, countries that are already operating Russian VVER nuclear power plants (NPPs), such as Ukraine, have been somewhat stuck because only one company outside Russia makes the necessary fuel. Nor is Russia’s nuclear industry dominance in decline. A full 50% of NPPs currently under construction are Russian models going up in Turkey, Bangladesh, and Hungary, among others.

The near future is no less compromised. Much of the new generation of U.S. nuclear technology, on which hopes of the U.S. reclaiming the nuclear vanguard from Russia and China rest, relies on a higher enrichment level fuel called HALEU. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) estimates that demand will hit 40 metric tons of HALEU just by 2030. But it is only made in Russia. Bill Gates-backed TerraPower, for one, was forced in 2022 to delay by years the rollout of its Natrium Sodium-Cooled Fast Reactor because of the lack of HALEU fuel.

With this reality, sanctioning Russia’s nuclear industry remains a fantasy. If the West is serious about fully isolating Russia economically or about the energy transition, it needs to at very least expand its own enrichment capacity. DOE is busily investing in U.S. enrichment aspirations, and the European Atomic Energy Community, Euratom, is also exploring options for the continent. But these things take time. Construction can take years, and the uranium mining, conversion, and enrichment itself takes at least one year. Unfortunately, current global fuel supplies are estimated to be no more than 18 months. Other countries could probably move faster but are precluded by non-proliferation and nuclear safety regimes, which in the U.S. are praised as the “gold standard” of nuclear regulation but which have essentially prevented any commercial scale nuclear development in the U.S. for 40 years. In the meantime, Russian nuclear dominance persists and its keystone position in the world’s nuclear industry continues.

The Kremlin’s ongoing energy leverage also encompasses the metals and minerals essential to the energy transition. Wind turbines require several critical minerals, and electric vehicles are heavy in lithium, nickel, cobalt, zinc, and other rare earth commodities. Solar panels also require nickel and zinc, as well as silicon, copper and others. China and Russia are the world’s leading silicon mining countries. Russia is the world’s third biggest nickel exporter, with its Siberian Norilsk Nickel company the world’s largest producer of high-grade nickel. Germany, for one, imports almost 40% of its nickel from Russia. Russia also sells palladium and is a key exporter of copper. Lithium, the key element in the lithium ion batteries that propel electric vehicles, is one of the few energy transition minerals for which Russia is not a big market force. Rosatom, Russia’s State Nuclear Energy Corporation, is working to fix that.

Unlike with nuclear, the western world has sanctioned much of Russia’s commodities trade, or imposed high tariffs. But this has only served to make the metals and minerals necessary for the energy transition harder to get and much more expensive. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent commodities prices soaring, up well over 50% since February 2022. Zinc, nickel, and other metals hit record prices thereafter. These price surges served to prolong some of the energy transition hardships and delays caused by China’s supply chain crunches from its COVID-19 lockdown, which caused global shortages in wind turbines, solar panels, and their component parts.

The conundrum this creates for policymakers is twisted. To take action against Russia’s nuclear industry or minerals exports will set back the very diversification of energy sources necessary to minimize Putin’s energy leverage. It will also hurt the momentum towards a nuclear and carbon-free power sector, and slow the energy transition. If Rosatom brings its planned large lithium mine into production, for example, it will support the electrification of transport and further reduce Russian oil and gas revenues. But if Putin is left the ability to hold nuclear power hostage all over the world, as he did Europe with natural gas, odds are that he will use that advantage to the western world’s disadvantage. We can easily imagine countries plunged into darkness by Russia as it demands concessions in exchange for nuclear fuel. It’s not like this hasn’t happened before with other energy sources. If Putin somehow ekes out a win in Ukraine or otherwise holds onto power, the West can expect retribution for supporting Kyiv. This may well include nuclear and commodities manipulation.

But if Putin loses power, the prospects of energy sector chaos or even a failed Russian state are just as dangerous. Perhaps the Wagner militia group, which owns extensive mines in Africa, will end up running Russia’s lithium and uranium mines and the enrichment facilities. With Russia already providing nuclear support to Iran, it is not far fetched to imagine weapons-grade uranium enrichment and fabrication cooperation between a future Wagner uranium monopoly in post-Putin Russia and anti-West Islamic fundamentalists or even terrorist groups. This would be a nightmare scenario.

Despite best efforts, exactly how the West will wake from the nightmare of Putin, avoid the nightmare of a post-Putin collapse, and also protect the energy transition remains unclear. Hopefully the best minds in governments around the world are looking for a path forward.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com