Wilmar Jensen passed the California bar and started practicing law the same year that Dwight D. Eisenhower became President and Elizabeth II took the throne as Queen of the United Kingdom.

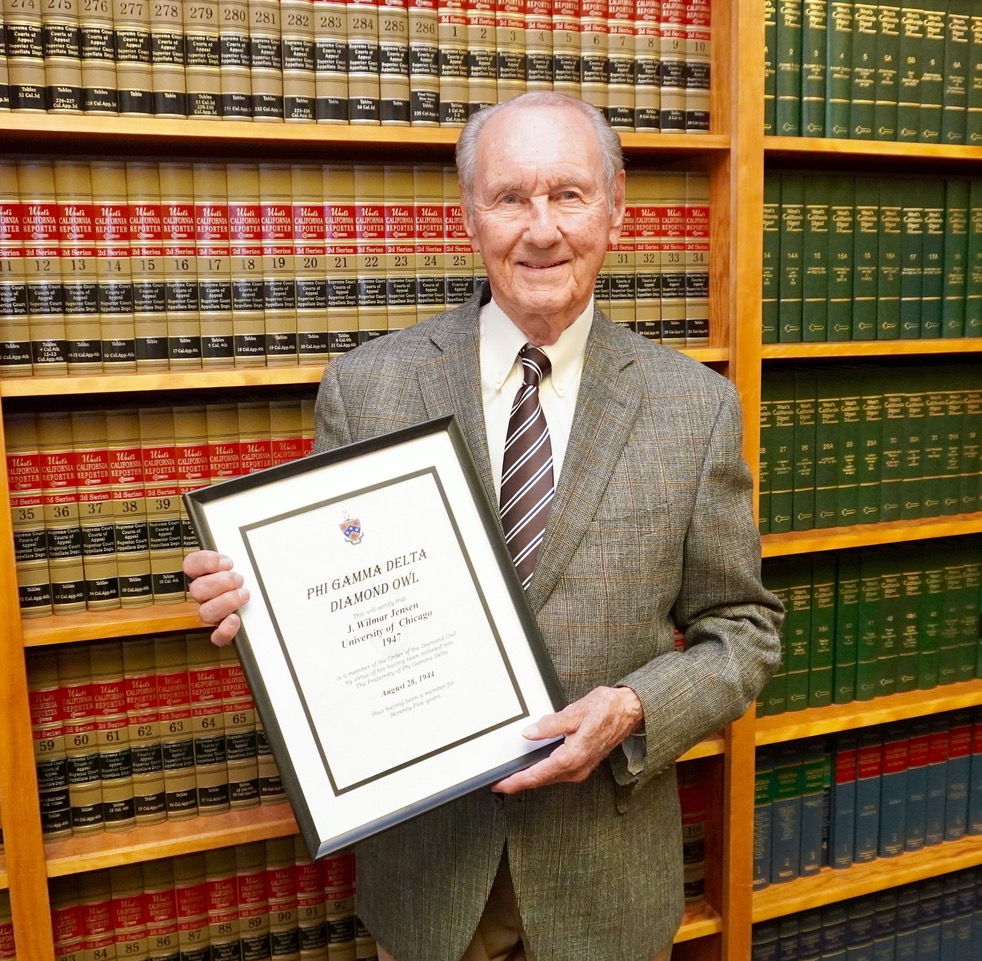

Seventy years later, Jensen is still a practicing attorney in Modesto, California. He turned 95 in December and has no plans of stopping anytime soon. “I enjoy my work and I want to keep going,” he says.

While a record number of younger workers in the U.S. have been quitting their jobs amid the Great Resignation, a number of older workers are staying put, with some working into their 80s and 90s. The reasons are varied: some don’t have the savings to retire, or need to stay on the payroll to keep receiving health insurance benefits. For others, it’s job satisfaction and the desire to stay mentally sharp that keeps them working.

Carmine Rende, Jr., an 85-year-old senior project engineer who recently relocated from Florida to Illinois, appreciated the mental stimulation working into his 80s provided him until he recently retired due to ill health. “It’s got to be a challenge, and it’s got to be meaningful. Otherwise, it isn’t worth it,” he says.

For most of his career, Rende worked for other people, so he had little say in the projects he took on. But as his own boss, he was able to work on a contract basis and could pick and choose the assignments that interested him. His regular clients included the Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts and Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company, so he was on the road a lot, fortunately to mostly desirable destinations, such as Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Jamaica, and Saint Martin.

During the pandemic, both the Great Resignation and the Great Retirement were in the news constantly, with labor statistics indicating that unprecedented numbers of workers were leaving their jobs and older workers were leaving the workforce entirely. But another trend also emerged: The Great Return, with older workers re-entering the workforce to join those who never left, according to Martha J. Deevy, Stanford Center on Longevity’s Associate Director and Senior Research Scholar.

Deevy expects that older workers’ desire to work longer will continue. Self-reported health rates indicate that the vast majority of people ages 65 to 84 feel healthy enough to work, she says. “But workers will want to work differently, more flexibly. I think the question is how quickly will employers respond and create opportunities,” she says. Some colleges are even offering courses catering to workers and retirees in their 50s and 60s to help them enter the next phase of their careers.

It is the flexibility and autonomy that has kept Jensen in the legal field for seven decades, along with the daily interaction he has with different clients.

Jensen started out as a trial lawyer, like many young lawyers do. But he hated it. “As soon as I could get away from it, I did,” he says. He moved into estate planning, trusts, and probate law and has never looked back. “I think it’s an easier and more enjoyable way to practice.” His son, Mark Jensen, joined the practice in 1987. Every once in a while, new clients or ones who haven’t seen the older Jensen in awhile, make the mistaken assumption that they will be meeting with his son. “There’s any number of people that figured I was dead,” Jensen says. “They would just be stunned to see me.”

His advice to anyone starting out and hoping to have a lasting career as long running as his is threefold. First, figure out what you want to do—ideally something you are interested in. Second, work hard. “You have to get up in the morning, put on your pants and go to work and not monkey around,” he says. And thirdly, maintain a good relationship with your family. Without that, it will make getting ahead a lot harder.

At 77, John Van Horn is a youngster compared to Jensen. Southern California-based Van Horn works 40 to 50 hours a week as editor and publisher of a small parking industry magazine and has no plans of slowing down anytime soon. He never even considered retiring. “I enjoy what I do, so why stop?” he says. Van Horn considers his work a part of his life, the same way family, hobbies, and travel are. “They all blur together.”

Remembering his own father’s decline once he retired, Van Horn has decided to keep working to keep himself young. “He began a long slide downhill until he passed away,” he says. “I don’t want that.”

A common refrain among older workers is that they might not be so eager to continue working if they had to answer to someone else. “That was one of the things that I was definite about,” says Jensen. “I didn’t want to be working for anybody else.”

When Nina Shilling, 84, left her private therapy practice in New York and moved to Seattle nearly a decade and a half ago, she wasn’t quite sure how her career would evolve. She briefly considered working at a clinic.

“I was very ambivalent about it,” she says. “I didn’t know if in my seventies I wanted to be commuting and if I wanted to be responsible to somebody else’s requirements. At that point, I think that [working for someone else] clearly became a disqualifier.”

Sometimes, the disqualifier can be from the employer’s side. Older workers are not always appreciated, says Louise Aronson, geriatrician and professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and author of Elderhood: Redefining Aging, Transforming Medicine, Reimagining Life. “There are countries that have mandatory retirement ages, even as we have longevity,” she says. “That is insanity.” Some of the assumptions that underpin arguments against hiring older workers include the idea that they are slower and more expensive than younger workers.

Aronson argues that there are huge benefits to having people with different skill sets and of varying ages. “We know that older people are more likely to make the right decision when presented with information. They are more likely to have emotional intelligence. And, at work teams that have people of varying ages tend to be particularly productive,” she says.

Assigning arbitrary ages for retirement just doesn’t make sense, says Aronson. “If you pick an age, you’re going to really harm a huge percentage of people, and lose all kinds of opportunities for society and individuals.”

Therapist Shilling remembers being asked about a decade ago how long she planned to keep working.

“I said, ‘As long as people want to come to see me.’”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com