Florida Governor Ron DeSantis recently taunted business leaders in The Wall Street Journal column announcing “Old-fashioned corporate Republicanism won’t do in a world where the left has hijacked big business…policies that benefit corporate America don’t necessarily serve the interests of America’s people and economy.” It used to be obvious that CEOs were reliably Republican. Corporate executives wanted lower taxes, less regulation, and a stable economy. They were usually men with military experience who moved with their families out to the suburbs. Ronald Reagan was their favorite president: pro-business, pro-free markets, and anti-government. Historically, 57.7 percent of big company CEOs contributed to the GOP but only 18.6 percent contributed to Democrats, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research.

It was an anomaly that FDR’s administration, as a Democratic team, was packed with Wall Streeters. The Eisenhower team was more typical for the GOP with many business leaders on board—in fact two with the same name Charles Wilson. “Engine Charlie” was the CEO of GM and “Electric Charlie” was the CEO of GE. The interests of big business and GOP politics were presumed to be in tight alignment with poor Engine Charlie haunted to his deathbed by the misquote “What is good for General Motors is good for the US.” (He actually said the reverse.)

But now the cracks are showing. Most CEOs are still Republican—between 60 and 70 percent, in every decade since the 1980s. But at the top, CEOs aren’t afraid to break ranks with the GOP, especially on social issues. In return Republican politicians are punishing corporations with legislation and threats of investigations.

More from TIME

The CEOs themselves have changed. Business priorities have changed to include sustainability, ESG, and diversity, not just tax policy. And the Republican Party has changed into the party of Trump. This is the story of how the GOP lost Big Business.

Corporations started caring about sustainability

The rise of the corporate sustainability report was the first trickle. In the 1980s and 1990s, companies started believing they could thrive while becoming greener and more socially responsible, and they wanted to get credit for their actions. The number of companies that file sustainability reports has grown by 100 times over the past three decades. The number of B-Corps, which take sustainability one step further, has risen to over 4000, including Ben & Jerry’s and Patagonia. More reporting doesn’t necessarily mean more progress—critics of the movement say accountability can be vague – but even by pursuing sustainability in name companies were moving further from the Republican Party line.

Clinton was a business-friendly Democrat

Following 12 years of Republican presidencies, Bill Clinton successfully won two terms as a “New Democrat”—read business-friendly, not tax-and-spend. He championed free trade and signed NAFTA in his first term. [Co-author Mark Penn was a key Clinton campaign advisor.] He pushed financial deregulation, culminating in the repeal of Glass-Steagall in 1999. And while the business community had quietly worried about Reagan’s deficit handling, Clinton balanced the budget and ran a surplus for four years in a row. For a Democrat, Clinton won a fair amount of business support from executives satisfied that he wasn’t as profligate as other liberals.

The rise of tech CEOs, which coincided with the rise of Obama

The rise of Silicon Valley ushered in a new breed of CEOs. Tech executives had different perspective, cultures, and values. Whether they were libertarians or progressives or nonpolitical, they definitely weren’t suburban, religious conservatives.

Clinton had received some Silicon Valley support from the first wave of Internet entrepreneurs, but the tech leaders really flexed their financial power for Obama in 2008. They liked Obama because he got it; he used their products, embracing social media from the start. Major Obama donors included Google’s Eric Schmidt, LinkedIn’s Reid Hoffman, and Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg. Even Tim Cook donated a couple thousand.

Tech CEOs grew in influence during the Obama years because they had an open invitation to the White House. Jack Dorsey moderated a Twitter town hall with Obama. Google averaged a meeting a week at the White House as it lobbied successfully for its own interests, including getting an FTC antitrust investigation shut down. Obama supported immigration and patent reforms that the tech companies liked, even when the unions opposed them. Both culturally and politically, tech was getting its way.

CEOs turn to activism to promote social harmony

CEOs believe that the free markets work best when people believe civil society is functioning smoothly. They abhor divisive rhetoric intended to inflame racial and ethnic divides.

Tech CEOs were the first executives to drive social activism against Republican governments. They were willing to throw around their size and cultural weight, often using social media, their home turf. Tim Cook, perhaps the country’s most prominent gay CEO, also criticized the law. When North Carolina passed its “bathroom bill” in 2017, PayPal CEO Dan Schulman was among the first to respond by canceling the company’s plans to build a new global operations center.

These stands spread beyond tech. Companies from the heartland like Walmart, AT&T, UPS, and NASCAR came out against antigay legislation. Financial institutions like Bank of America and Deutsche Bank took action as well. These megacorporations commanded large, diverse workforces; they felt the pressure to listen to their employees, who often internally and externally led the protests on such issues. They also became more comfortable with the language of diversity and inclusion as they feared social backlash.

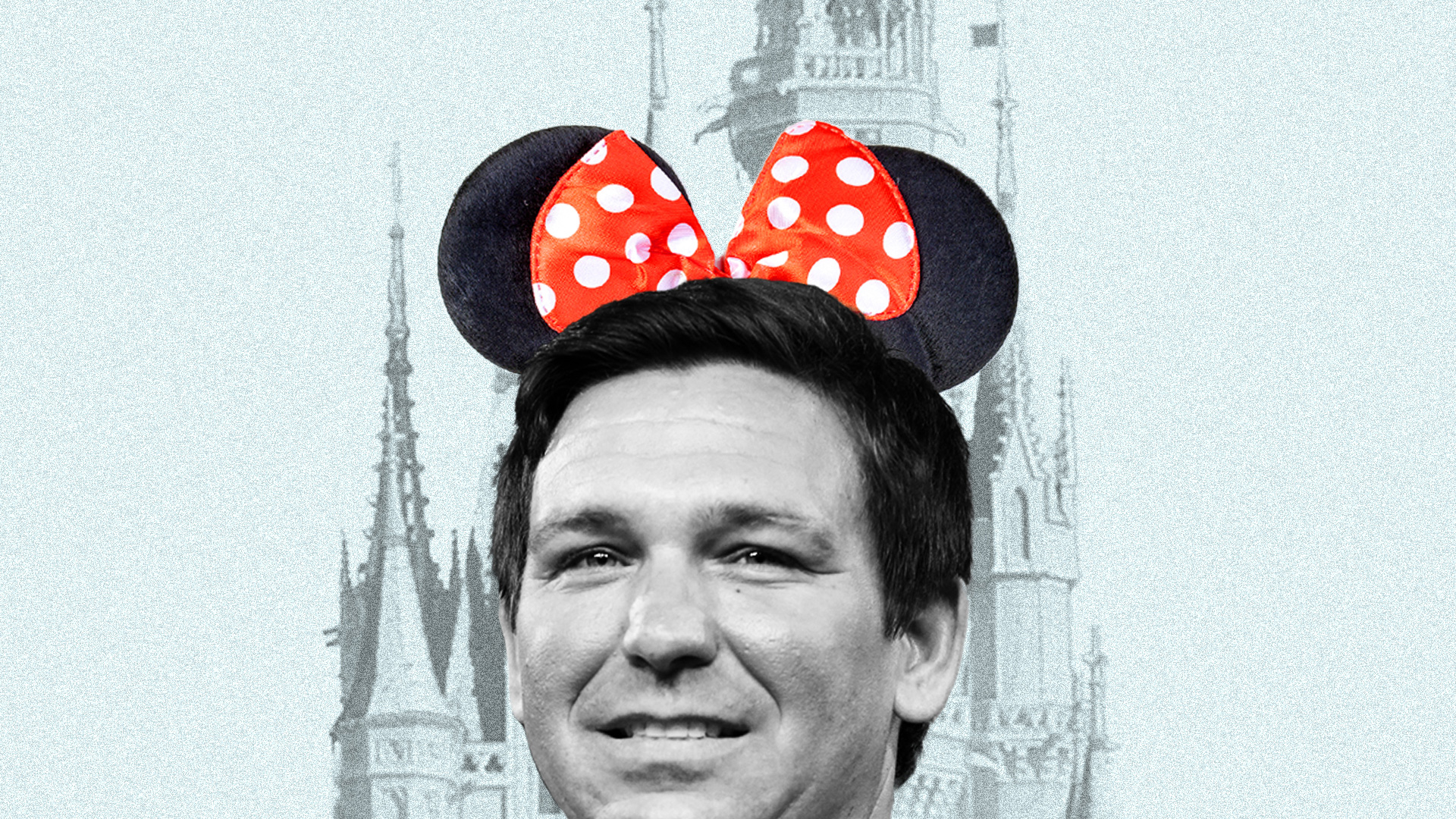

We’ll see how far business goes as Republicans in power push back, too. In 2022, Disney may have picked the wrong fight with Florida. Then-Disney CEO Bob Chapek bent to employee pressure to call out the state’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill, which would restrict discussions of gender and sexuality in the classroom; in retaliation, Governor Ron DeSantis threatened to take away Disney’s special tax status.

CEOs double down on ESG

ESG is the other warfront. It’s not just sustainability reports; financial institutions are increasingly championing ESG as the overall business model. In response, West Virginia barred banks like Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan from government contracts because they have reduced coal investments; Louisiana and Arkansas have pulled hundreds of millions from BlackRock for being too focused on environmental issues. BlackRock is one of the biggest targets as CEO Larry Fink has repeatedly defended ESG as “stakeholder capitalism” and smart business rather than “woke.” After winning the House back in the 2022 midterms, the GOP is getting ready to investigate and subpoena financial institutions. In previous decades, Big Business and Republicans might gripe about each other in private but profess solidarity publicly; now they don’t hide their differences.

Big Business doesn’t like Trump’s Republican Party, especially its treatment of democracy

Donald Trump’s takeover of the Republican Party could have been the best thing for the business community. Instead very few major corporate leaders publicly endorsed either of his campaigns for office with Trump’s financial support largely coming from small donors. In 2020 the overwhelming majority of billionaires supported the Biden campaign. CEOs loved Trump’s tax cuts and deregulation. But it was outweighed by Trump’s isolationist populism. In today’s globalist era, big businesses rely on open immigration for the best workers in the world. They opposed Trump’s tariffs, anti-immigration policies, and xenophobic rhetoric.

Above all Big Business wants stability—stable democracy, stable markets—which Trump showed he couldn’t provide. CEOs had rallied around him enthusiastically in January 2017 after the creation of his business advisory council, but that affection was short-lived. In August 2017, when Trump equated violent Nazi protestors with peaceful civil rights advocates in Charlottesville, then Merck CEO Kenneth Frazier spoke out against Trump’s failure to condemn the white supremacist hate groups and resigned from Trump’s American Manufacturing Council. Initially, the business community wasn’t sure if they were all going to leave Trump’s business advisory councils, but within days, more than 200 business leaders rallied around one another, resigning en masse—the first refusal to heed a U.S. president’s call to national service.

Three years later, when Trump was denying the reality of the 2020 election results, scores of big business leaders joined forces in meetings to persuade GOP legislators to smooth the succession process quickly. Following the worst assault on the Capitol since 1812, companies pledged to use their political influence to defend democracy in its aftermath by pledging a temporary moratorium on those 127 legislators who refused to ratify the already certified Electoral College results. When GOP politicians attacked those CEOs who spoke out as “woke,” they rallied to support each other in defiance with, for example, the CEOs of United and American Airlines standing in support of the CEO of Delta.

Business stood by their resistance to those GOP politicians undermining the electoral process. According to 2022 FEC filings, total corporate giving to election objectors fell a staggering 60 percent from calendar year 2019, the equivalent stage of the last election cycle. Putting this in context: All corporate political spending on Congress is down 28 percent; corporate support for GOP non-objecting members of Congress slipped that same 28 percent; and corporate giving to Democratic members of Congress fell just 19 percent. While businesses have lost some interest in supporting Congressional campaigns in general, by this measure they are three times more wary of assisting objectors.

At the same time major business leaders have strengthened Election Day by guaranteeing millions of workers paid time off to vote. They created a bypass around politicians’ inability to secure Election Day as a national holiday. As business leaders increasingly stand up for democracy they find themselves further from a GOP that remains consumed by Trump.

These changes have created a tectonic shift in the political plates. Now it seems more likely that Democratic politicians go to bridge and factory openings while Republican politicians rail at critical race theory and promote anti-vaccine conspiracies. The GOP’s current threat is to expensively jeopardize the full faith and credit of the U.S. by refusing to raise the debt limit, as they enthusiastically did under three times under the Trump Administration—when the national debt grew greater in four years than it had in the prior 240 years. Business leaders have taken note of this pattern.

The Republicans could repair their relationship with CEOs by staying out of the culture war, dumping their extremists, and returning to lower taxes and deregulation. The Democrats could swoop in and become the pro-business party, but they’ll need to defang the progressive wing’s antitrust and anti-wealth crusades. There’s an opportunity for long-term political realignment here: Big Business is now a free agent.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com