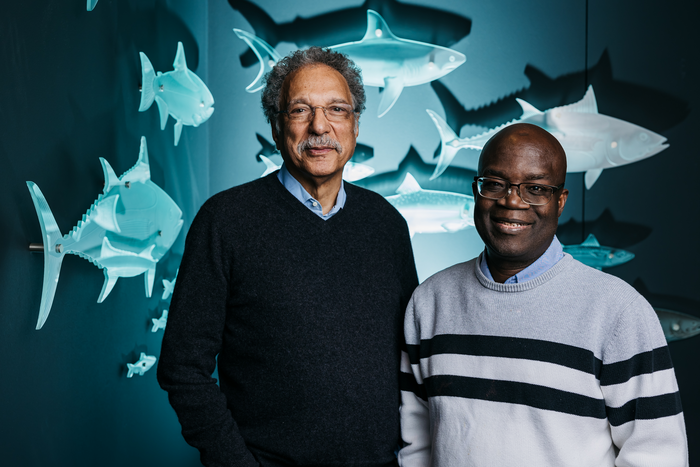

When I sat down with two of my personal ocean heroes, fisheries biologist Daniel Pauly and economist Rashid Sumaila, science took something of a back seat to James Brown and racial justice. Our conversation was inspired not only by their having just jointly won the prestigious Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, but also by their wish to honor Black history within conservation.

For nearly two decades, I have admired Pauly and Sumaila for their deep wisdom and prolific publishing on topics like overfishing, food security, and marine protected areas—they are each the most-cited researcher in their respective fields. They are professors (and collaborators) at the University of British Columbia, where Pauly founded and leads the Sea Around Us project. Rarely in all these years have I heard them publicly discuss their personal lives. But as two Black men at the top of their game, they decided they wanted to open up about their experiences with racism, their personal heroes, and why they do the work they do. Our conversation was wonderfully forthright.

Of course, we got into the science of it all too—fisheries subsidies, the connections between fisheries and climate, and their answers to my favorite question: What if we get it right? Most pressingly, they had used the occasion of their award to issue an urgent call to ban fishing on high seas.

As we spoke, world leaders were meeting at the United Nations to negotiate a much-anticipated high seas treaty that could make that possible. And in the days since our conversation, the U.N. on March 4 finalized the treaty text—marking an historic deal to protect our oceans after two decades of negotiations.

The following is abridged and edited for clarity.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: Let’s start with the message you wanted to spread as part of winning the Tyler Prize: the need for a ban on fishing the high seas. What would be the ecological and economic impacts of such a ban?

Daniel Pauly: The effect would certainly not be that we would have no fish, because the high seas produce only 5% to 8% of all fish that are landed. These fish are highly migratory, and they could instead be caught within a country’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). In fact, if they were not caught by the five or six countries that monopolize fishing on the high seas, they would be caught by a far wider range of countries.

So, the overall catch would not be affected. Lots of other problems, such as slavery at sea, would be reduced because all fishing would take place under the governance of countries—as opposed to the currently vague international jurisdiction. And of course, the boats would not have to travel so far, which would reduce carbon emissions.

More from TIME

Rashid Sumaila: It’s also important to reflect on the potential equity from a ban of fishing on high seas, which is the area more than two hundred nautical miles from shore. Smaller countries in the Caribbean or in the Pacific would actually improve their catch. So, it’s important to think of these issues in terms of biodiversity, climate change, economics, and also equity.

(While the final U.N. treaty does not heed the specific call to ban fishing on the high seas, it does, among other things, create a framework for establishing marine protected areas on the high seas. Via email, Pauly wrote that he was “excited by the positive news” that “showed humanity can agree on common issues.” And Sumaila sees the agreement as putting us “firmly on the way to turning the high seas into a ‘fish bank’ for the world,” starting with the goal of protecting 30% of the high seas by 2030—a leap over the current 2%.)

AEJ: A lot of your work focuses on equity, grounded in addressing food security, fishing rights, sustainable management, what we might call ‘ocean justice.’ Do you conceive of your scientific research as being directed towards justice?

DP: I have always seen my work as trying to strike a balance between developed and developing countries. I grew up in Europe. And I began my career explicitly trying to develop methods that would enable my colleagues—fishery scientists in developing countries—to do fisheries assessments, as they didn’t have access to the same information as colleagues in the Global North.

Later with colleagues I also developed a huge database of fish—Fishbase—for the same reason: because people in the Global South had no access to information. They couldn’t get the books or the papers. They got bibliographies—but that helped them as much as cookbooks in the middle of a famine. So we made the stuff available—first on diskettes, then CD-ROMs, then the Internet.

And now I lead the Sea Around Us project, which makes data available to enable people to document the fisheries for every country in the same way. I think we should have more stuff of that kind, where we treat everybody the same way and then we can compare the data and we can see global trends much better.

RS: As an African, equity is central and something very dear to my heart. Until Africa really gives the same opportunity to women as it does to men, we will never make it because half of our brain power is lost because the girls don’t get the same opportunity. It is about diversity, it’s about inclusion, it’s about bringing all the brains that we have on board. All the data shows that talent is distributed equally all over the world but what is not distributed equally is opportunity.

I go to global meetings, and all you see represented are North America, Europe, Australia, and then maybe Cape Town, right? That is not the world. They forget Latin America, Asia, and most of Africa. We’ve got to be inclusive so we can move this world forward. I also work with colleagues on intergenerational equity. So, it’s not only about those of us here, it’s also about the future generations. If you eat up the salmon and the tuna, are you going to leave just jellyfish for them?

AEJ: Daniel, reading your biography last year I learned so much about how race has shaped your path, which may be surprising to some because many people who read your work and have seen you speak don’t even know that you are Black.

DP: Yes. This was on purpose. I was born in Paris, I grew up in Switzerland, studied in Germany, and I’m culturally very conscious that I’m European. But people always questioned where I’m from. I was so fed up with this, that I thought the best thing I could do is move to a country where people are brown, then I’ll stop getting asked this question.

I began studying agronomy in Germany, but the agronomy department was full of Nazis. Real Nazis, because they still had them in Germany at that time. So I shifted into the fisheries department. I went to Ghana for field work, and quickly learned that I’m not African, because I got my first sunburn! But I had seen the racism to which people there were exposed—mainly because they were darker than me—and how it limited their ability to do things.

My whole life was structured by race because I decided to expatriate myself because of it. Then I pursued a career that did not emphasize race and me being biracial. I have avoided exposing myself to this toxic brew of negativism that I thought would prevent me from working. But a few years ago, when a lot of things were happening with the Black Lives Matter movement, it taught me that I have to be more than just a role model. I have to be actively engaged. I want to address specifically the issues of race.

AEJ: Rashid, I assume your story is quite different because with your darker skin you can’t hide. What kind of role has race played in your career?

RS: My relationship with race is very different from Daniel. We’re both Black, but him starting off in Europe and me starting off in the African continent—it’s really different because of colonialism, because of slavery. You realize growing up as a young African, this idea that “everybody’s better than you.” It’s difficult to even say, but you enter a room and almost everyone thinks you are nobody. They assume you are poor.

I will tell you something I haven’t told anyone: I get a lot of confidence from James Brown. ‘Say it loud! I’m Black and I’m proud.” And I tell you, that music liberated me in a big way.

AEJ: Apart from James Brown, is there anyone in Black history who’s really shaped your thinking? It’s okay if it’s someone whose dance moves aren’t as good.

RS: I’ll start with my own grandfather. He used to say “you should walk on the earth as if it feels pain.” Later I realized this is really advanced environmentalism. Also, Wangari Maathai—the Black, Kenyan Nobel Peace Prize winner who planted 50 million trees or more. She fought not only for the environment, but also for democracy and social justice.

And an African-American, Robert Bullard, who is described as the father of environmental justice. He said that every human being has a right to a clean environment, regardless of color or sex.

DP: For me, I’m very political. I’m a person of the left. One of my heroes is Nelson Mandela. I knew of him long before he was the saint that he has become. As a student, I went to the African National Congress in London—they were in a rundown office and they were trying to publicize who Mandela was and the struggle they were in.

And Angela Davis. I’ve never met her, which is a pity, but I followed her. I named my daughter after her. I also have a wild cousin who was a mathematician and a Black nationalist. I had the option of doing the same that he did—raising hell—which is a good thing, but I chose to be a scientist.

AEJ: You’ve been raising a little hell to end overfishing, I would say. So, the question that’s been driving my work lately is “What if we get it right?” In fact, that’s the title of my forthcoming book. I’m curious to hear from you, if we do charge ahead with all these ocean-climate-justice solutions, what do you imagine the world would look like?

RS: If we manage to get it right, we will have what I call “Infinity Fish.” We will have an ocean teeming with life, which can therefore support our coastal communities and small-scale Indigenous peoples, forever. Almost like a trust. We’ll be able to draw on our ocean resources, the services we get from them, forever.

I’ve also started thinking about universal basic income in the world. There’s money to do this, it’s just that we’re afraid to tax anybody these days. If we can implement a universal basic income, it will free the world to do what we need to do.

DP: Let’s say we are 50 years from now and things have worked out. What would that involve? We would have to have broken the political might of Big Oil. We have to break their stranglehold over our politics. Industrial might must be used toward renewable energy instead of warfare. Certain forms of over consumption will no longer be possible.

We would have resolved the world problem of demography. The earth cannot sustain 10 billion people—the population we will be at very soon. We will have to get to a point where our population becomes stable, then gradually declines, because humanity cannot continue to eat up the earth—the ocean and the land—at the rate it does now.

RS: The inequality of consumption patterns is also a big issue. For example, when one person flies with a private jet and pumps out as much CO2 as is used by a whole village in Africa or Asia. The consumption levels in the developing world need to increase, and in the rest of the world they will have to come down. There is a level in the middle for everybody. In the Global North, we are supposed to consume and consume and consume—but the extra consumption doesn’t really add anything to our quality of life.

AEJ: How do you connect the dots between your work on fisheries and the climate solutions that we need to pursue?

RS: If you overfish, if you fish down the food web and take down the habitat, you are making the stocks more vulnerable to climate change. It’s like covid and people with preconditions. If you’re healthier and you’re hit by covid, you’re more likely to withstand it.

DP: One of the direct impacts on climate change are the emissions of vessels that are subsidized to fish. So, if fishing vessels were not subsidized, fewer would remain—we would have the same catch, but with less effort and fewer emissions.

And another thing is that the fish populations that are reduced have less individuals and thus less genetic variability. For example, if you have lots of fish in the water, there will be some that are pre-adapted to higher temperatures. So they would be the ancestors of the future population. So you have to have genetic variability and marine protected areas or rebuilding programs to ensure the fish are abundant and can meet the challenge of the higher temperatures.

AEJ: Of all of your achievements, is there something that you’re particularly proud of?

DP: I am most proud of the work that I do on the relationship between fish and oxygen and respiration. It was the topic of my dissertation over 40 years ago. At the time, this research was met with a resounding silence because global warming was not an issue.

A few years ago, I began working on this problem again. As our oceans warm, fish need more oxygen, but the water contains less oxygen, which means fish have difficulty breathing. If they don’t get enough oxygen, they grow more slowly, or they move to cooler waters, or they perish. Now, because of increasing global warming, this topic is very urgent.

RS: What I’m most proud of are the spaces that I’ve been able to reach with my message. I never dreamed I could have those opportunities: to be in the White House, in the Senate, to be with then Prince Charles, at the African Union. You can do your science and publish in the journals and go to sleep. No. I am bringing my work to the people who can take the science and actually do something with it. And that makes me happy.

—

Johnson is a marine biologist, policy expert, and writer. She is co-founder of the non-profit think tank Urban Ocean Lab, co-editor of the bestselling climate anthology All We Can Save, and co-creator of the podcast How to Save a Planet. Her forthcoming book—What If We Get It Right?: Visions of Climate Futures—will be published by One World/PRH in autumn 2023.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com