Night had settled upon the roof of the world. With a jingling of harness and the clipclop of hooves, a small caravan wound slowly up the 17,000-ft. pass. Ahead lay the snowy summits of the Himalayas, an ocean of wind-whipped peaks and ranges that have served Tibet as a rampart since time began. Cavalrymen with slung rifles spurred forward; state officials in furs, wearing the dangling turquoise earrings of their rank, sat tiredly in the saddle; rangy muleteers in peaked caps with big earlaps goaded the baggage train up the steep path. As they passed a cairn of rocks topped by brightly colored flags printed with Buddhist prayers, each pious Tibetan added a stone to the mound, murmured the traditional litany: “So-ya-la-so.”

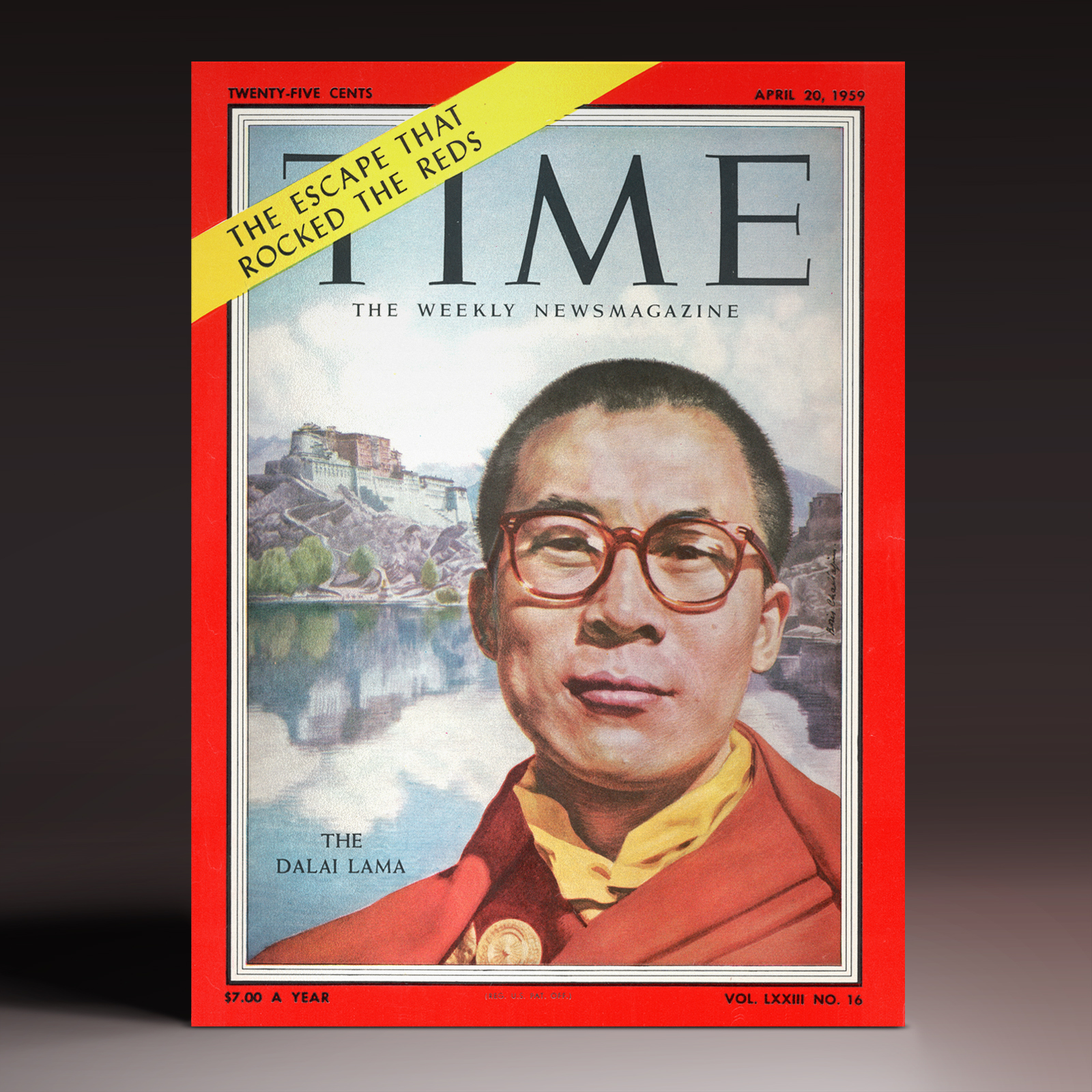

They listened tensely for the sound of gunfire behind them, which would mean that the pursuing Red Chinese had clashed with the rearguard of Khamba tribesmen. Up front, scouts probed carefully to make sure Communist paratroops had not been dropped in the pass to bar their way. All of them—the 35 Khambas of the rearguard, the 75 officials, soldiers and muleteers—were charged with a solemn responsibility: to make good the escape from Tibet of the God-King in their midst—the 23-year-old 14th Dalai Lama.

Journey to Safety. As the Dalai Lama and his escort fled by night and hid by day in lamaseries, villages and Khamba encampments, the furious Red Chinese boasted that they had put down the three-day revolt in Lhasa that had served to cover the God-King’s escape. Point-blank artillery fire drove diehard lamas from the Norbulingka, summer palace on the city’s outskirts. Red infantrymen surged into the vast warrens of the Potala winter palace, rounded up defiant monks in narrow passages and dark rooms where flickering butter lamps made Tibet’s grotesque gods and demons seem to caper on the walls. The corpses of hundreds of slain Lhasans lay in the streets and parks of the city, from the gutted medical college on Chakpori hill to the barricaded main avenue of Barkhor. Rifle fire and the hammer of machine guns rattled the windows of the Indian consulate general, whose single radio transmitter is the only communication link with the free world. And Red Chinese columns and planes crisscrossed the barren plateaus and narrow valleys of Tibet in search of the missing Dalai Lama.

Last week word came that the Dalai Lama had reached safety in the village of Towang, just across the Indian border. His two-week march to the frontier, it was said, had been screened from Red planes by mist and low clouds conjured up by the prayers of Buddhist holy men.

Aroused Asia. The 1956 rape of Hungary by the Soviet Union did not rouse the frustrated rage in Asia that it did in Western Europe and the U.S. White v. white colonialism does not stir Asians much. But the crime against Tibet has opened many Asian eyes. The independent Times of Indonesia warned that Red China was losing what few friends it had left. From Japan to Ceylon, Asians angrily recalled the fine words of Red China’s Premier Chou En-lai at the Bandung Conference in 1955, when he warmly embraced Nehru’s Panch Shila (Five Principles) and specifically promised to respect “the rights of the people of all countries to choose freely a way of life as well as political and economic systems.” India’s press and public demanded that Nehru be at least as forthright in denouncing Red China as he was in denouncing Britain and France during the Suez invasion, and were impatient with his bland impeachments of Peking. In Buddhist Cambodia, a newspaper that often echoes Cambodia’s neutralist royal family urged Red China to withdraw its troops from Tibet and prove “that it respects the hopes of all peoples for liberty and self-determination.”

Buffer State. Over the centuries, the mountain-locked nation of Tibet has often been overrun by invaders—Mongols, Manchus and Gurkhas, but most often Chinese. Whenever China was strong, it would send a garrison to occupy Lhasa. Whenever China was weak Tibetans would drive the garrison out. In 1904, uneasy about Russian encroachments in central Asia, the British launched an expedition from India and captured Lhasa with little difficulty. To keep each other at arm’s length, Britain and Czarist Russia agreed to make a buffer state of Tibet and signed the Convention of 1907 recognizing China’s “suzerainty” over Tibet. No one bothered to define suzerainty, nor did anyone consult the Tibetans.

Large chunks of Tibetan territory disappeared. The provinces of Amdo and Kham were taken by China, Sikkim ended up with India, Ladakh went to Kashmir. Today there are more Tibetans living outside Tibet than in it (1,700,000 to 1,300,000).

The Yellow Hat. The nation’s sole defense over the centuries was the Three Precious Jewels of Tibetan Buddhism: the Buddha, the Doctrine and the Community. Power lay with the contending monks and noblemen. The Red Hat sect, which allows its lamas to marry, was gradually overborne by the celibate Yellow Hat sect. This was made official in 1557 when a Mongol khan gave the seal of rulership to the leading Yellow Hat monk and named him Dalai (Ocean of Wisdom) Lama. The fifth Dalai Lama is famous for building the vast Potala. He also felt the need to honor his favorite teacher by naming him the Panchen (Teacher) Lama, and put in his keeping Tibet’s second largest city, Shigatse. He thus created a rivalry that has plagued Tibet ever since. Generally, the Dalai Lama has had the support of whatever power is ruling in India, and the Panchen Lama of the ruling power in China.

The Search. The present Dalai Lama’s predecessor was one of the greatest of his line. He lived long and governed well. In 1933, warned by the State Oracle that his end was approaching, he summoned a photographer all the way from Nepal to take a final picture, and shortly thereafter this most sacred Living Buddha shed the garment of his body in order to assume another. While by Lamaist teaching his soul went to dwell for 49 days in the famed Lake Chö Kor Gye before taking up residence in a newborn infant, his corpse was embalmed by being cooked in yak butter and salt, its face painted with gold, and the mummy seated upright facing south in a shrine of the Potala.

Who was the newborn infant in whom his soul was reincarnated? A four-year search began, and became another of the endless legends of Tibet. The regent, who ruled the state during the interregnum, journeyed to Lake Chö Kor Gye and, after gazing into its mirrored waters, reported a vision of a three-storied lamasery whose golden roof was necked with turquoise, and a winding road that led to a gabled farmhouse of a type unknown to Lhasans. Search parties went out in all directions without success. Finally the oracle of Samye monastery, Tibet’s oldest, went into a trance, recommended that the search be extended to the Chinese province of Tsinghai, whose Amdo region is largely populated by Tibetans.

In Tsinghai, the priestly caravan was met by the ninth Panchen Lama, who had fled to China after difficulties with the 13th Dalai Lama. Near death himself, the Panchen Lama was not bitter, and suggested the names of three young boys who might be possible candidates. The first child had already died when the lamas reached him; the second ran screaming at the sight of them. At the home of the third child, on the shores of fabled Lake Koko Nor, the monks were struck dumb. Just as in the regent’s vision, there was a peasant house with a gabled roof, there was a winding road and, beyond, a three-storied lamasery whose golden dome sparkled with turquoise tiles.

As the awed monks approached the farmhouse, a small boy rushed toward them from the kitchen crying, “Lama! Lama!” His name was Lhamo Dhondup; he was two years old; and one of his brothers was already a Living Buddha at Kumbum monastery. Interrogated, the child gave the correct title of every official in the party, even picking out those who were disguised as servants. The second test required that he examine duplicate rosaries, liturgical drums, bells, bronze thunderbolts, and teacups, and select the ones that had belonged to him in his previous life as the 13th Dalai Lama. He did it with ease. Overjoyed, the lamas also found that the child had the required physical marks: large ears, and moles on his body that represented a second pair of arms. Then, in the final test, he was offered a choice of identical walking sticks. To the monks’ horror, little Lhamo chose the wrong one—but at once threw it away. Seizing the right stick, he refused to be parted from it.

Finding the Dalai Lama proved easier than getting him home to Lhasa. The Chinese warlord of Tsinghai demanded $30,000 before he would let the boy leave. Glumly, the lamas paid it and set out for Tibet. They were stopped at the border. The warlord wanted more money, and it took two years of negotiations and a further payment of $90,000 before the Dalai Lama, by then four years old, could go in triumph to the palace of Potala.

Polygyny & Prayer. The Tibet he would one day rule is a preserved relic of ancient oriental feudalism. Twice as large as Texas, lying in the very heart of Asia, it is a land of mountains and craterlike valleys that seem to have been ripped from the moon. Its people are handsome, cheerful and indescribably dirty. About four-fifths of them work to support one-fifth, who are shut up in lamaseries. What little land is not owned by the monks belongs either to the Dalai Lama or to about 150 noble families, who have kept their names and acres intact down the centuries by a mixture of polygyny and polyandry. To safeguard their ancestral estate, three brothers will often share a single wife, and all children are considered to be fathered by the eldest of the brothers. Recently, a highborn Lhasa woman was simultaneously married to a local nobleman, to the Foreign Minister of Tibet, and to the Foreign Minister’s son by another wife.

Religion is lived by all the people. Hundreds of lamaseries house thousands upon thousands of monks and nuns whose days are spent in meditation and prayer. There are nearly as many Living Buddhas as there are lamaseries, including one female incarnation whose name translates as “Thunderbolt Sow.” Prayer is everywhere, on the lips of men and on flags and bits of paper stamped with woodblock imprints of the sacred words: “Om mani padme hum [Hail, the jewel in the lotus).” The phrase flutters from tall poles outside villages, from trees and cairns; it is stuffed inside the chortens’ hollow towers at crossroads, and revolves constantly in the prayer wheels in every temple, nearly every house. There is gold in Tibet that cannot be mined for fear of offending the gods of earth, though panning gold from the river beds is permitted.

When a Tibetan dies, his body is carried to the top of a mortuary hill, hacked into pieces by body breakers and left to be picked clean to the bone by scavenger birds and beasts. Tibetan sons keep their fathers’ skulls and use them as drinking cups out of filial piety. On stormy days, when blizzards smother the high mountain passes, lamas cut out paper horses and scatter them to the winds to carry help to any poor traveler foundering in the deep snow. Meeting a stranger, a Tibetan sticks out his tongue in friendly greeting.

Tibet is cold, filled with silence and bones, haunted by demons; yet Tibetans are a strangely happy people. In the brief two months of summer, they swarm from their dirty, smoke-filled houses, set up white tents with blue trimmings on the river meadows, sing, drink milk beer and tell stories. They splash together in the streams for their first baths of the year. Nearly every visitor to penetrate the forbidden land has been enchanted by its people. They do few things terribly well, but everything with zest. Explorer Fosco Maraini believes they have found the secret of liberty, which is “to live like a flower or a stone; sheltering from the rain in bad weather, enjoying the sun if it is fine, breathing in the fullness of the afternoon, the sweetness of evening, the mysteriousness of night, with equal joy and wisdom. Perhaps that is why you hear singing everywhere, fine music that fades away into space as if it were spontaneously generated.” Coming back to the outside world from Tibet, travelers miss the serenity and peace, the brimful feeling of being at one with nature and the universe, the unfailing courtesy of Tibetans, and their pious avoidance of cruelty to any living thing.

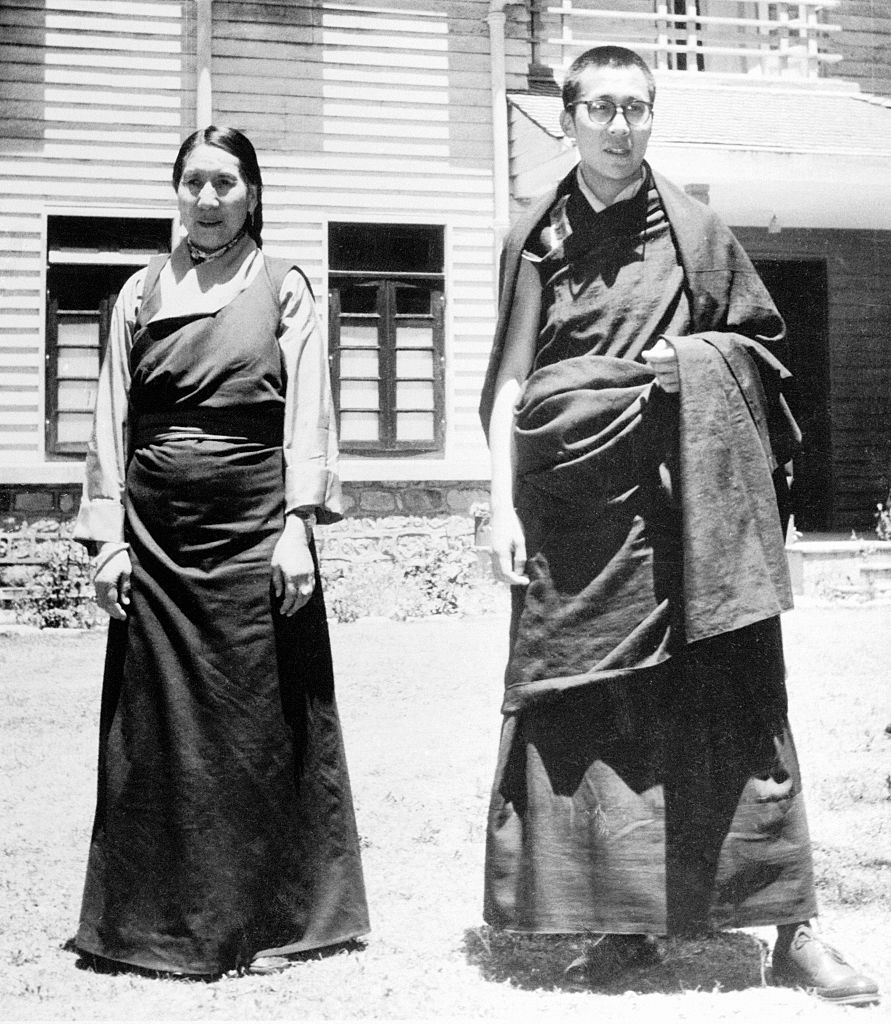

Defender of the Faith. For the four-year-old Dalai Lama, arrival in Tibet meant an end to childhood. He was enthroned at Lhasa in 1940 and endowed with many names—the Tender, Glorious One, the Holy One, the Mighty of Speech, the Excellent Understanding, the Absolute Wisdom, the Defender of the Faith. He sat through the hours-long ceremonies without complaint, a slim, grave-eyed boy with protuberant ears.

The Dalai Lama’s peasant family came with him to Lhasa, and his father was made a noble, but he saw little of them. His days were spent with monkish tutors, in learning the Tantric texts of Lamaism and the complex religious ceremonials. At night he went to sleep in the enormous, fortresslike Potala, and could hear the palace gates close harshly and the ringing shouts of the watchmen as they marched through the long, twisting corridors. Without playmates or attending parents, the Dalai Lama matured early, and at 14 he visited Lhasa’s great monasteries of Drepung and Sera to engage in religious disputation with their learned abbots. This was a critical moment, for upon his intelligence and agility of mind would depend the future balance of power. He would not be deposed should he fail the examination, but he could be turned into a puppet—a Living Buddha who was easily manipulated by shrewd and able monks.

At Drepung monastery thousands of red-robed lamas crouched on their haunches in a graveled courtyard while the 14-year-old Dalai Lama preached to them on the Tantric texts in a clear, boyish voice, but with the composure and assurance of an adult. A Tibetan-speaking Westerner was there, an Austrian named Heinrich Harrer, who had escaped from a prisoner-of-war camp in India and painfully made his way to asylum in Lhasa. The debate that followed between the abbot and the Dalai Lama was a genuine contest of wits, says Harrer, in which the God-King was “never for a moment disconcerted,” while the venerable abbot “was hard put to hold his own.”

But the Dalai Lama was still too young to govern, and his state was run for him by regents. Two of them quarreled, and Lhasa was rocked by a brief civil war in 1947, in which howitzers were used to end the defiance of the monks of Sera lamasery. More important to Tibet and the Dalai Lama was another civil war: that in China. As Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists were driven from the mainland to Formosa, it was inevitable that the Reds would soon attempt to assert the Chinese suzerainty that had been largely ineffectual for nearly 40 years.

In 1950 the test came. When a Red Chinese “liberation” army was poised on the Tibetan frontier, the nomad Khamba tribesmen asked Lhasa if it intended to fight. The Dalai Lama’s advisers could not make up their minds. The fortress of Chamdo surrendered with scarcely a shot fired, and the Khambas decided that Lhasa had lost its nerve, and made no move to stop the Reds.

The young Dalai Lama was seldom consulted in such matters. He passed his time in study and in a new absorption in Western gadgets. He took many photographs, often wandered on the terraces of the Potala armed with a telescope with which he could examine the busy life of his city without ever being permitted to join in it. Each spring he traveled in solemn procession through ranks of bowing, weeping people to the summer palace; each autumn he solemnly returned to the Potala. The Austrian Harrer tutored him in Western science and technology, found in the Dalai Lama an insatiable urge for learning, a fascination with modern matters such as the construction of jet planes, but a total acceptance of his own godhead. Once, remarking on his previous incarnation as the 13th Dalai Lama, he said musingly: “It is funny that the former body was so fond of horses and that they mean so little to me.”

As the Red Chinese pushed toward Lhasa, the Tibetan National Assembly sent an urgent plea to the United Nations for help against the aggressors. It was rejected with the pious hope that China and Tibet would unite peacefully. The uncertain Tibetan government called on the State Oracle to decide what the Dalai Lama should do. He urged flight.

Before leaving Lhasa, the Dalai Lama was hastily invested with full power as the ruler of Tibet and the regency abolished. In command of his country for the first time, just as it seemed on the point of dissolution, the Dalai Lama withdrew to the Indian border but did not cross over. Since it was clear that no power on earth was interested in aiding Tibet, the God-King opened negotiations at a distance with Red China. In May 1951, a 17-point agreement was signed between the two nations: Red China agreed that Tibet could retain autonomy and promised no change in the Dalai Lama’s status, function or power. Tibet surrendered control of its foreign relations to Red China.

Journey to Peking. Returning to Lhasa, the 17-year-old Dalai Lama received the Red emissaries with frank curiosity. Much of what they proposed—schools, roads, hospitals, light industry—met his approval. Many Tibetans welcomed the break with the feudal past, argued: “We must learn modern methods from someone—why not the Chinese?” The Dalai Lama made a six-month visit to Mao Tse-tung’s new China, listened patiently to lectures on Marxism and Leninism, saw factories, dams, parades. Back in Tibet, Red technicians set to work. Some 3,000 Tibetan students were shipped off to school in Red China. But things went wrong from the start. The hard-driving Red cadres filled with Communist zeal made little impression on the individualistic Tibetans, who felt that the inner perfection of a man’s soul was more important than an asphalt surface on a road. Sighed the Dalai Lama: “China and Tibet are like fire and wood.”

His words were proved true in the border province of Kham, where the Reds had been longer in control. The lamaseries of Kham were looted of their treasure and their land collectivized. Nomad Khamba tribesmen were driven from the pastureland they had used for centuries. Tribal chiefs resented their loss of power te the commissars. The Khambas, great shaggy men often 6 ft. tall, with leather boots, 3-ft. swords and rifles they are born and die with, fought back. Snipers bushwhacked lone Red couriers on the new road to Lhasa. Khamba bands ambushed military convoys. The embittered monks drove off the Chinese farmers sent to take over their land. To teach them a lesson. the Chinese Reds sent bombing planes and leveled the intransigent lamaseries.

For four years the guerrilla war raged along the border. More and more dispossessed Khambas crossed over into Tibet proper and roused their fellow tribesmen in the Tsangpo valley to join the revolt. In Lhasa, monks grumbled at the religion-destroying teachings of the Red Chinese; Tibetans complained at soaring prices and the confiscation of grain and wool. The Reds applied pressure on the Dalai Lama to quiet his people. To an anxious crowd assembled in the Norbulingka gardens, the God-King said blandly: “If the Chinese Communists have come to Tibet to help us, it is most important that they should respect our social system, culture, customs and habits. If Chinese Communists do not understand the conditions and harm or injure our people, you should immediately report the facts to the government, and we can immediately ask that the guilty ones be sent back to China.”

When the rebel Khamba tribesmen began attacking Red outposts within 40 miles of Lhasa, the Red commander demanded that the Dalai Lama prove his “solidarity” by ordering his 5,000-man bodyguard against the rebels. It was a shrewd move, for in the past Lhasa had had its own troubles with the Khambas, who recognized the spiritual rule of the Dalai Lama but had a habit of killing his tax gatherers and robbing caravans. The God-King solved it neatly: he sent a message to the Khambas saying cryptically that “bloodshed was not the answer,” but flatly refused to lend Tibetan troops on a punitive expedition.

Unable to break the Dalai Lama’s will, the Red commander decided on a show of strength. Last month, while Lhasa was still crowded with monks, pilgrims and peasants who had attended the New Year’s Festival, the Red general sent a curt note ordering the Dalai Lama to appear, alone, at Communist headquarters.

Lhasa was appalled. It was unthinkable that a message should go directly to the Dalai Lama instead of being reverently submitted through his Cabinet. It was even worse to demand that the Living Buddha attend a meeting alone without his ceremonial train of senior abbots and court officials. On hearing the news, the Dalai Lama’s mother burst into tears. Thousands of weeping women surged around the Indian consulate general and begged the consul to accompany them while they handed a protest petition to the Red Chinese. The monks of the city’s three great lamaseries prepared to die before letting the Dalai Lama be taken from them. Hidden stores of arms were passed out to the furious populace. Khamba tribesmen with their rifles, swords and lean, savage dogs began to filter into Lhasa. The nervous Chinese set up machine-gun posts, trained artillery on the Potala and the Norbulingka palaces.

On March 17 the Dalai Lama, his mother, sister and two brothers, guarded by a fanatic escort, slipped out of Lhasa and moved north, where there were few Chinese patrols. Traveling only at night, the party carefully circled the city and headed south toward the Indian border. On March 19 the fighting started in

Lhasa, and only after three days, when the city’s whitewashed houses, its palaces and lamaseries were a smoldering shambles, did the Red Chinese realize they had been outwitted, and set up the propaganda cry that the Dalai Lama had been kidnaped and was being held “by duress.”

Asian Algeria. The smashing of the revolt in Lhasa was as brutal as the action of Soviet Russian tanks in Budapest. But Tibet is not another Hungary: it is more likely to become Red China’s Algeria, a festering war to the knife that can be neither won nor lost. The Communist garrisons should be able to hold the cities and the main roads. They can even find a handful of Tibetan collaborators, like their tame puppet, the tenth Panchen Lama, a wan young man of 22 who is unable to control the monks of his own lamaseries. But the Red troops, estimated at 60,000-80,000, must be supplied from a base 70 miles distant, over a single, hazardous road that can be easily cut by Khamba guerrillas.

At week’s end the Khamba rebels were reportedly joined by equally fierce Amdowa and Golok tribesmen, spreading the fires of revolt the length and breadth of Tibet, and putting into the field against the Chinese Reds an estimated 100,000 warriors, who were carrying the fight to the Chinese provinces of Szechwan and Tsinghai as well as Tibet proper. The Red radio protested plaintively that “reactionary elements” from China itself had joined the battle.

The rest of the world cheered the rebels and denounced their oppressors but made no other move. India, the biggest free neighbor, was giving shamefaced support to Premier Nehru’s reiterated insistence that “India was anxious to have friendly relations with Red China.”

When the Dalai Lama this week finally made his way through the jungles of Assam to the airfield at Bomdila, he was welcomed by officials of the Indian government before being flown to a mountain resort at a safe distance from the Tibetan border—so as not to give offense to Red China. He will be inundated by the good wishes of the free world, but for the foreseeable future, the Dalai Lama and 3,000,000 Tibetan patriots can only put their trust—as their ancestors did before them —in the Three Precious Jewels of Tibetan Buddhism: the Buddha, the Doctrine and the Community.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com