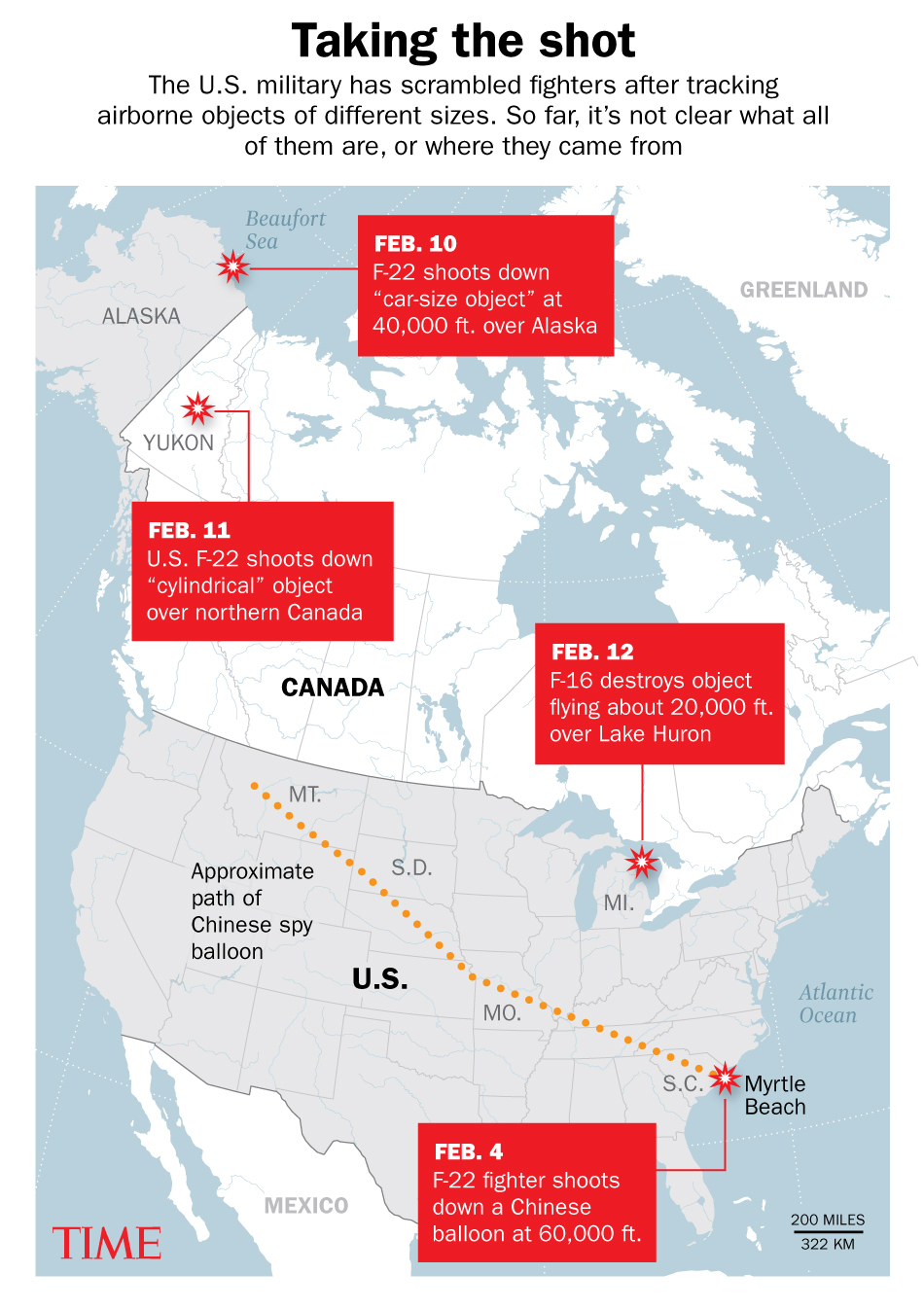

In the first two weeks of February, the U.S. Air Force has shot down four flying objects that have intruded on the skies over North America. The deployment of force is unprecedented for the U.S. during peacetime—leveraging some of the U.S. military’s most advanced fighter planes, surveillance tools, and expensive air-to-air missiles.

The first object shot down was an alleged Chinese surveillance balloon that the Biden Administration says was part of a years-long scheme to spy on nations across the Earth. But so far, officials have been much less clear about what the other objects are. One shot down over Alaska Feb. 10 was described as a “car-sized object” that did not appear to have a propulsion source. One downed over Canada the next day was described as “cylindrical,” potentially a balloon, but smaller than the Chinese balloon.

READ MORE: Everything We Know About ‘Unidentified Objects’ Shot Down

That balloon, which was publicly spotted over Montana Feb. 1 and carried sensors capable of spying on conversations on the ground, revealed an entirely new class of threat to U.S. air space. Experts say two things are happening as a result: First, the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and other agencies tasked with watching for airborne incursions have recalibrated their detection methods to pick up smaller, slower-moving objects that they weren’t previously paying attention to. Second, the military decided that shooting these objects out of the sky and collecting the wreckage is one sure way to quickly learn where they’re coming from and what threat they pose.

“We need to get a better sense of what these things are and whether or not they’re worth engaging with,” says Ian Williams, deputy director of CSIS’s Missile Defense Project.

Either way—it’s unlikely that using Sidewinder air-to-air missiles at about $400,000 a pop fired from $150 million F-22 stealth fighters will be an economical response in the long term. “If this is something we’re gonna start doing on the regular, we may want to look for more cost effective ways,” Williams says.

What we know about the objects

First, it’s probably not aliens, experts agree. The White House and intelligence officials have echoed this point. “Unidentified flying object” in this case means just that—an object that is flying and has not been identified.

The U.S. has released some details about the four shootings but it’s still not clear what all of them are or where they came from.

On Feb. 10, an F-22 shot down a “car-size object” at 40,000 feet over Alaska that officials said had no obvious propulsion. White House spokesperson John Kirby said its origins were unclear. The Pentagon had said it could be a potential risk to civilian air traffic.

On Feb. 11, a U.S. F-22 shot down a “cylindrical” object over northern Canada. The U.S. and Canada worked together to take the object down. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said that the country would analyze the wreckage.

A National Security spokesperson said before the fourth flying object was downed that “these objects did not closely resemble and were much smaller than the [People Republic of China] balloon,” CNN reported.

On Feb. 12, an F-16 used a missile to destroy an airborne object flying at about 20,000 feet over Lake Huron in Michigan. The Department of Defense noted that the location chosen to shoot it down allowed them to “avoid impact to people on the ground while improving chances for debris recovery.”

An important point with these new objects is also that they posed a possible threat to civilian aviation. While the Chinese balloon was at 60,000 feet of altitude—well above the ceiling for passenger planes—the other objects were flying much lower, closer to the 20,000-40,000 feet that commercial aircraft reach.

Why are we spotting more flying objects?

Since the U.S. shot down the alleged Chinese spy balloon on Feb. 4 off South Carolina—and admitted to at least three previous incursions into the country in recent years—it has been finding more slow-moving flying objects in the sky. That’s because the military now knows to look for them.

The Chinese balloon—which Beijing maintains is for civilian weather observation—forced military officials, lawmakers and the American public to start scrutinizing U.S. surveillance of its airspace more closely.

Experts say NORAD was previously focusing on spotting fast-moving objects that generated a lot of heat—think missiles, bombers and fighter jets. When radars and other surveillance methods are tuned to those threats, it can be easy to miss slow-moving balloons, which also might not show up on radar as well.

U.S. officials have worked to improve the ability of existing radars to track these flying objects down. “We have been more closely scrutinizing our airspace at these altitudes, including enhancing our radar, which may at least partly explain the increase in objects that we’ve detected over the past week,” Melissa Dalton, the assistant secretary of defense for homeland defense and hemispheric affairs, said at a news conference on Sunday.

General Glen VanHerck, NORAD’s commander, said the U.S. has adjusted its radar to track slower objects. “With some adjustments, we’ve been able to get a better categorization of radar tracks now,” he said, “and that’s why I think you’re seeing these, plus there’s a heightened alert to look for this information.” VanHerck had previously admitted that the balloons exposed a “gap” in American air defenses.

“Now they have some experience and know what these things look like, on radar, they’re able to refine filters to look for them… more efficiently,” Williams says. “It’s about finding that balance of getting what you need but not getting so much that you’re just chasing flocks of birds around.”

Air defense also appears to be becoming more of a priority for Congress. “What I think this shows…is that we really have to declare that we’re going to defend our airspace. And then we need to invest,” House Intelligence Committee Chairman Mike Turner told CNN. “This shows some of the problems and gaps that we have. We need to fill those as soon as possible because we certainly now ascertain there is a threat.”

Gathering intel

One advantage to shooting down so many of these objects is that once they are recovered on the ground, they offer a lot for military and intelligence officials to analyze. “There’s been some great intel gathering,” says Riki M. Ellison, chairman & founder of Missile Defense Advocacy Alliance.

These objects are in remote locations; officials noted that recovery of the one shot down in Alaska has been hampered by limited daylight and arctic weather conditions.

But while shooting these objects down is one of the only ways to learn about them right now, experts say the U.S. should consider a sustainable policy to address them once we know more about the threat they pose.

“We’re shooting these things down with pretty expensive missiles; if this is something we’re gonna start doing on the regular, we may want to look for more cost effective ways,” Williams of CSIS says.

Ellison is advocating for greater radar capabilities to ensure that the U.S. can simultaneously track these flying objects alongside other threats like bombers and missiles, and understand how best to engage with them.

So far, he worries that the American response has been disproportionate compared to China’s efforts “China wins that fight a little bit,” he says. “Look at the cost imposed on us and what we had to spend to defend against that; it’s very lopsided.”

It’s likely that these kinds of objects were always up there in the U.S. airspace but that shooting them down was not a priority. “We chose to tolerate them,” Ellison says.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Sanya Mansoor at sanya.mansoor@time.com