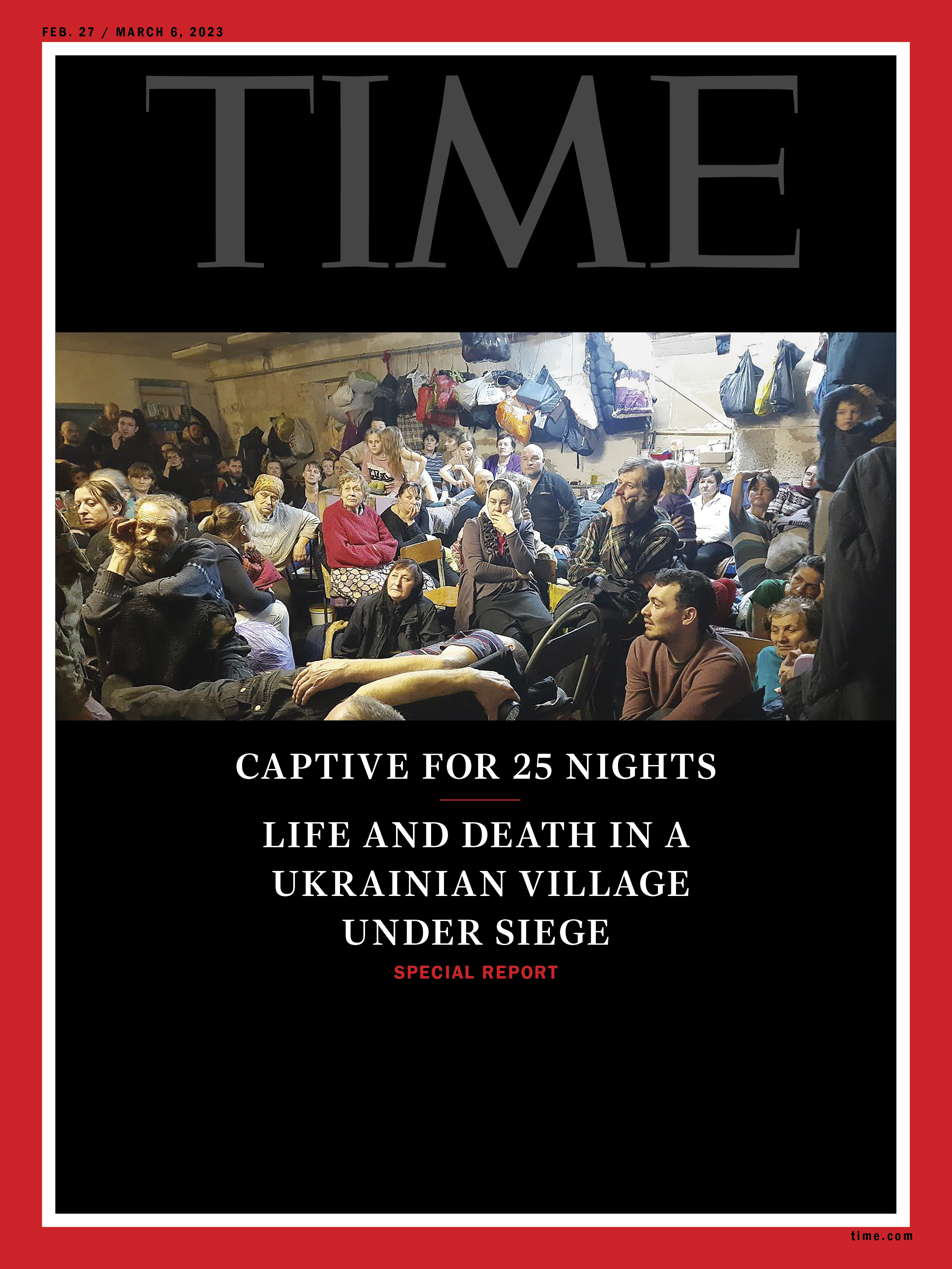

Seven days after the invasion of Ukraine, Russian troops entered the village of Yahidne. They forced the residents out of their homes and into the basement of the local school, which they had turned into their headquarters. Until they withdrew on March 30, 2022, the Russians kept almost the entire population of Yahidne—more than 360 people, including children and the elderly—in that basement for nearly a month.

It was so cramped, people had to sleep sitting up. Instead of a toilet, there were buckets. Food had to be foraged. There was no ventilation, so the oldest went crazy and died. The Russians did not allow the dead to be buried immediately, and when they finally did, they fired on the funeral.

“People jumped into the pit with the bodies,” says one six months later, recalling the ordeal, at a feast for those who emerged alive. Many had not.

In the intervening months, the survivors repeated their experience to one another, and to investigators working for justice. Their confinement in the basement may serve, one year after Vladimir Putin invaded on Feb. 24, as a microcosm of the sadism that arrived with the invaders. But to more than one survivor, what comes to mind is a concentration camp.

“What day,” one of them asks, “did people start going crazy?”

A year into the invasion, certain places in Ukraine—the Kyiv suburb of Bucha, the southern city of Mariupol—are known for what Russian forces did to the civilians there. To the list add the tiny village of Yahidne, which lay in the north of the country, directly in the path of the advancing army. As soon as the artillery barrages began, the informal village leader, a man named Valeriy Polhui, made a bomb shelter out of his cellar. When Svitlana Baranova and Lilia Bludsha, a travel agent and an engineer at Chernobyl, pulled into the village in a car struck by shrapnel, its windshield shattered, Valeriy took them in too.

There was fighting all around the village. Svitlana and Lilia called their families to say that it was too dangerous to leave Yahidne and that they would stay there a while longer. On March 3 the military vehicles entered the village in a long column. Valeriy hurried everyone—the nine members of his extended family and the two guests—into his makeshift bomb shelter.

From inside, they could hear heavy machinery driving into his yard, stomping, and gunfire. But that evening nobody discovered their hiding spot, thanks to Valeriy’s smart thinking: he hung a lock on the door to make it look as if it had been shut from the outside. The Russians pulled at the door and walked away. But the next day they broke the lock. Valeriy shouted:

“Don’t shoot, there are children here!”

Everything froze for a second, as if the person on the other side of the door hadn’t expected to hear a voice. Then the command came for everyone to come out, one by one. Valeriy went first. The next command to him was to lie down on the snow. The Russians took their phones and searched their contacts. If they saw the word Kyiv they asked for more details, as if this word in and of itself was a threat. They searched the house, found a uniform, and decided that Valeriy was in the military. He explained that he wasn’t. He spoke in Russian, but the soldier didn’t understand him.

“Military, military,” the soldier repeated, ignoring the explanation. The soldiers looked Asian, their Russian was broken, and Valeriy later learned that they were from Tuva, a region in the far east of Russia, one of the country’s poorest.

“Married?” a soldier asked Lilia.

“No,” she lied.

“Age?”

“32. Are you going to kill us?”

“Yes.”

Then they locked them back in Valeriy’s cellar. The next day, March 5, the Russians opened the cellar door and said:

“Get out. We’re taking you to the school basement.”

It was a gray, cold morning.

The village is bordered on one end by a pine forest and on the other by the Kyiv-Chernihiv highway. There are five streets, and Valeriy could see people being frog-marched to the school from each, slowly, family by family. Behind each family was a soldier pointing a machine gun at them. The Russians made the sick and elderly come. Their families moved them in wheelbarrows.

On the 500 meters that separate his house from the school, Valeriy counted 80 units of equipment: armored personnel carriers, tanks, mortars. Soldiers with red armbands were bustling about, hauling ammunition. By Lisova Street a dead body lay on the ground. Anatoliy Yaniuk had been shot in the head on March 3. He was 30 years old. The Russians had executed him when he refused to lie down on the ground in front of them. “I am on my own land, and I will not lay down in front of you.” Those were his last words, neighbors who saw the execution told his mother.

The school is a two-story white brick building on the edge of the village, in front of the forest. That morning chalkboards in the classrooms still had the academic assignments for Feb. 23 written on them. Armed soldiers scurried about military vehicles between the swings.

As they were herded into the basement, the people of Yahidne saw a fellow villager, Anatoliy Shevchenko, off to the side, blindfolded, his hands tied. Despite the cold he was sitting on the concrete parapet in a light sweater, with visible bruises on his body. The two soldiers next to him were brandishing their machine guns.

Olha Meniailo, an agronomist who was being forced into the cellar with her husband, son, daughter-in-law, and their 4-month-old son, noticed some of the military looked more experienced and some were boys in their teens. She felt sorry for the latter because they were just “kids.”

“Why did you come here?” she asked the Russian soldiers.

“We came to free you from the Nazis,” they repeated.

“There are no Nazis here,” said Olha. “You only ‘freed’ us from our homes.”

The largest room of the basement once housed the school gym, but now it reminded her of images of hell from ancient religious icons. “A candle flickers here and there,” she would remember later, “and in the dim light there are people next to each other with doomed expressions on their faces. It’s suffocating.”

Valeriy, his family, and Svitlana and Lilia were already in the basement, sharing the largest room with 150 other people. Later they calculated there was about half a square meter per person: 170 square meters, 367 people (including more than 70 children). They sat on the bench or on the floor, resting their heads on their neighbors’ shoulders, not knowing if they would live to see the next morning.

As the days went on people handled their fear differently. Some sat in a stupor, hugging their pet dogs. Others ran around looking for water and wondering how to survive.

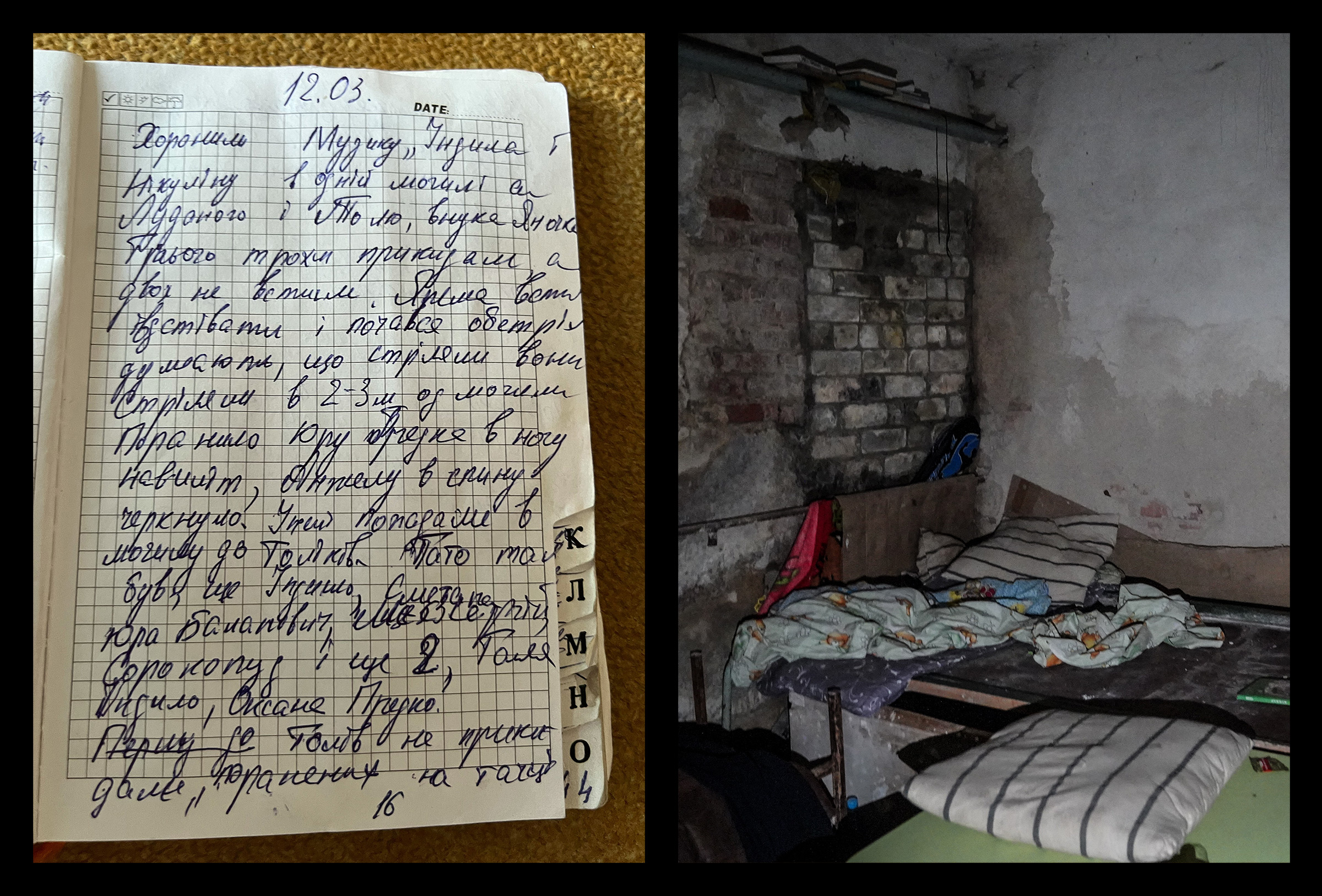

Olha decided she could stay sane by keeping her diary. Today the words are hard to make out—she wrote in the dark; flashlights were turned on only when absolutely necessary. Olha used her index finger to measure the width of the lines so that she wouldn’t write over things.

Day one—We tried to talk to the soldiers.

Day two—They took away everyone’s cell phones.

Day three—We started boiling water.

She stuck to the bare facts: she knew the diary could be seized and didn’t want anyone to know her innermost thoughts.

During the day, people sat in the basement on chairs, benches, and the floor. They slept sitting up. They used bulletin boards to make a platform for the children to lie on. The only way to stretch your legs in those cramped conditions was to stand up. Svitlana and Lilia would take turns lying on two chairs, while the other lay on the floor underneath.

The Russians had claimed that they sent the villagers into the basement for their “protection,” but it was clear they were human shields. The Russian military made their headquarters on the two floors above.

At first the captives were in such a state of shock that they didn’t even think much about food. Then they ate what they were able to bring from home. The Russians gave them some of their dry rations. Aboveground, the Russians took everything from people’s refrigerators. They slaughtered all the livestock. All of March the smell of grilled meat hung over the village.

When people got hungry, they looked to Valeriy for help. “Valeriy, what do we eat?” they asked him. He began looking among the Russians. He chose someone about his age, 38, with a red beard and red hair. The other soldiers called him Klen (Maple). None of the soldiers used their rank or real names with one another, only nicknames.

“There are almost 400 people here,” he told Klen, “and they all want to eat.” Klen was silent at first.

“OK, make a fire, but no smoke.”

Then he looked at Valeriy: “I see you’ll be responsible for everyone. Everything goes through you.” Valeriy’s heart sank. Klen hadn’t made a suggestion. It was an order.

They boiled water for the first time on the third day. They prepared baby food and every morning made porridge for the children. They figured out how to get water from the school well. It was not drinking water, but water nonetheless. Since there was no electricity, they pumped by hand. One stroke brought 100 to 150 milliliters of water; for food and tea, they needed 150 liters.

The prisoners watched enviously as the Russians drank from small juice boxes, and dreamed how they would buy some when they were free again. Sometimes the Russians would give them crackers from their rations, and one time they brought a wheelbarrow of sliced bread. Some of the bread was moldy, the rest was dirty, but the mothers still ran to the wheelbarrow, grabbed the slices of bread, and dusted them off to feed their children. The soldiers filmed the scene on their phones.

One time they brought bags of cereal and pasta. Valeriy wondered what brought on this gesture of goodwill. But when he took a closer look, he saw that the bags were leaking. They were transporting diesel fuel in the car, and it spilled on the bags of cereal. The people washed the pasta in water three times, boiled it, and ate it anyway.

The most humiliating thing was going to the toilet. They were allowed to use the toilet outside only during the day. But you weren’t allowed to leave the basement at night. There were three buckets in the gym for about 150 people. People stopped drinking water in the evening to keep from having to use them.

The first person died on day five. Dmytro Muzyka was 92. His wife Maria outlived her husband by just a few days. She too died in the basement. Another person died on day six. Then two in one day. From March 5 to March 30, 10 people would die from lack of oxygen, medicine, and care.

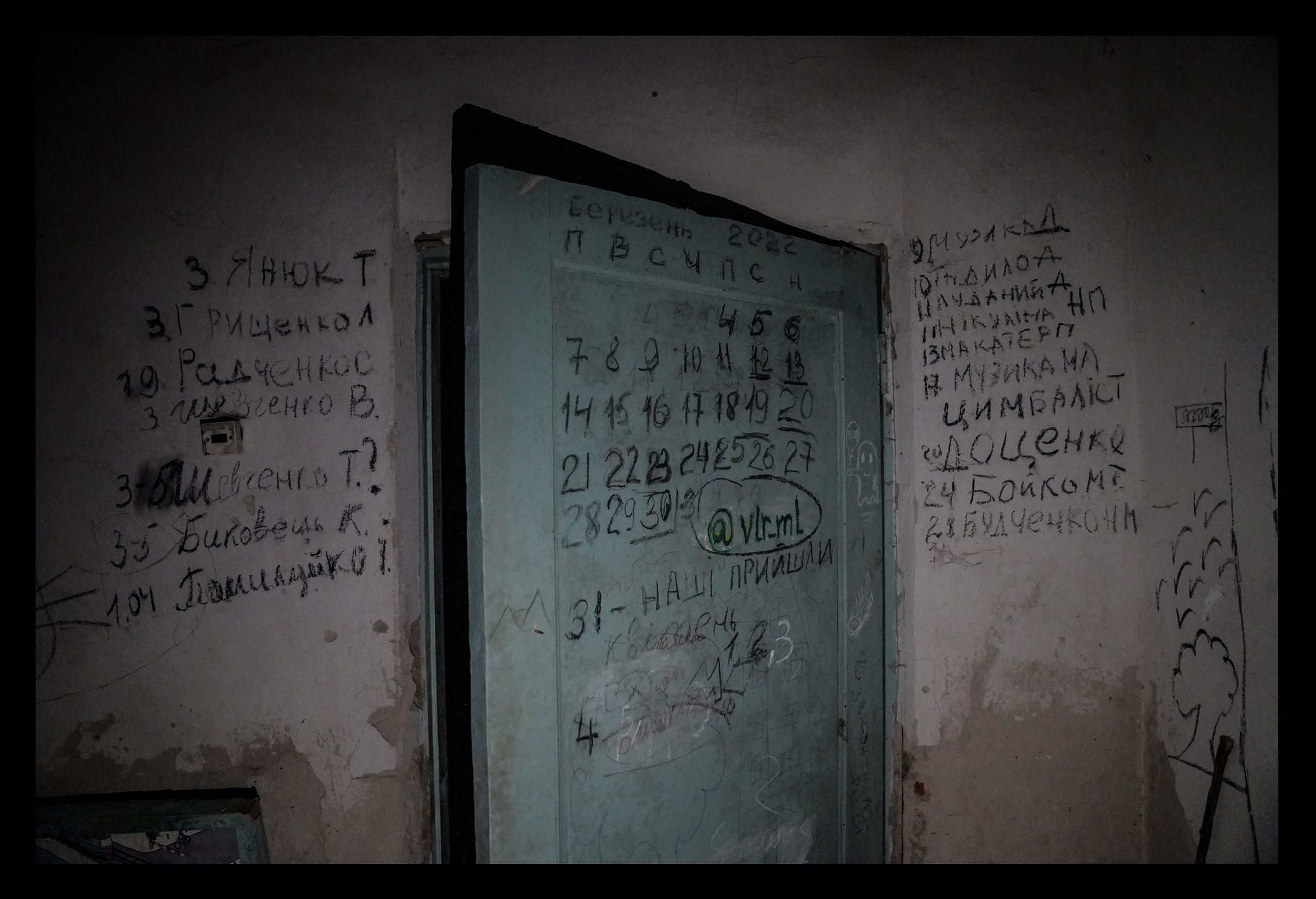

The list of the dead is etched on a wall, next to a calendar. Valentyna Danilova maintained both. Before the invasion she worked in the kindergarten, directly above where she was now being held along with her husband and 83-year-old mother. Valentyna found an ember near the cooking fire and used it to write the first date. Then it became a daily ritual. “Did you remember to write down the day?” the 5-year-old boy next to her would ask every morning. Later, she began writing the names of the dead next to the numbers.

The basement wasn’t heated, but the air was hot from the hundreds of bodies. The walls remained cold and condensation from people breathing ran down them, so that the people by the walls sat in puddles. But the real horror was the lack of oxygen. Valentyna compared it to a sinking ship—they were suffocating.

Some of the oldest couldn’t handle it. They didn’t recognize their children. Screamed. Had conversations with dead relatives. Revealed family secrets. Then they died, sitting in a chair.

By March 12, several corpses had accumulated. The Russian soldiers finally gave permission for them to be buried.

People in villages take their funerals very seriously. They spend decades planning what clothes they will be buried in, preparing embroidered towels that their relatives should hang on the cross. Now people were being buried without a coffin and without a cross. They were taken to the cemetery wrapped in sheets, in a wheelbarrow, their arms and legs hanging out.

Two pits were dug for the five dead. There wasn’t enough time to dig more—the Russians gave them only two hours for the funeral. If they took any longer, they would be shot. When the first bodies were lowered into the pit and the local priest, who was also kept in the basement, began saying the prayer, a Tiger armored vehicle drove up to the cemetery, stopped, and several men looked at the funeral brigade. They were wearing balaclavas and helmets so only their eyes were visible. The vehicle drove on, and a minute or two later the funeral was being fired on, with explosions all around the graves.

The men jumped into the pits with the bodies. The priest fell between gravestones and was hit by a falling tree. After the shelling, the wounded were taken to the basement in the same wheelbarrows they used to bring the bodies to the cemetery.

Klen, the red-haired soldier, ran the basement in what some of the prisoners describe as a concentration camp.

“You are being punished,” he would say when he locked the door during the day. People would plead to be let out, banging on the door, shouting that they were suffocating … nothing helped.

When someone with cancer asked him for permission to go home and get their medicine, Klen answered, “If things are so hard for you, there’s the forest—go hang yourself, it’ll get easier.”

Valeriy thought Klen hysterical and unbalanced, with a mania for controlling the prisoners in the basement. “Take one wrong step and he’ll shoot you on the spot.” He was also a zealous patriot. One time, Valeriy went up to Klen to ask permission for people to go home. The redheaded soldier listened to him, and then handed him a sheet of paper.

“Do you know the Russian anthem?”

“No.”

“What about the Soviet one?”

“I don’t know it.”

“Here’s the anthem. If someone wants to go home to get food, they have to sing the Russian anthem.”

Nobody sang the Russian anthem.

The people in the basement had no idea what was happening on the front, in Ukraine, in Kyiv, even in the local capital of Chernihiv. “We’ve captured all your cities,” the soldiers told them. But the people thought, If Russians had captured all the Ukrainian cities, why were they still in Yahidne?

A commander was supposed to go to Russia. He promised to bring back medicine. But he returned in two days.

“People are asking about pills,” Valeriy said. “Did you bring them?”

“I didn’t bring them and I won’t,” the commander told him. “Your partisans are mining the roads, we can’t make it to Russia.”

Great, so there is hope after all, Valeriy thought.

Meanwhile, health conditions were deteriorating. There was an outbreak of chicken pox. People coughed from the lack of air and the dust. Many had a temperature. People’s legs swelled from sitting all the time; they had open sores. The Russians could have given them antiseptic or cough lozenges, but most often their response was “We didn’t come here to treat you.” People continued to die, and when they did, their bodies were taken to the boiler room where the living went to wash.

But toward the end of March, speculation began to spread that the Russians were planning to leave. The people noticed increased movement; there was less security. A hidden joyous premonition of freedom was growing. “Everyone dreams about freedom,” Olha Meniailo wrote in her diary.

March 30 was the holiday known as Warm Oleksa. That morning, as they had done for nearly a month, the people went outside to the toilet and started preparing food. But at 11 a.m. they were sent back into the basement and locked in. There was a hole in the wooden door that was made to let in air. The soldiers shouted: If anyone goes near the door, we’ll shoot. But some people stood at a distance from the door and watched through the opening as the Russians were removing their equipment.

A sense of hope was growing inside everyone. But the prisoners were afraid to betray this hope even to their closest neighbors. Maybe these soldiers were leaving, but new ones would replace them? Maybe they were going to pretend to leave, then hide, and then start shooting as soon as people exited the basement?

The vehicles hummed and the noise receded. The humming was replaced by gunfire, which continued for some time, and then there was silence. There was complete, utter silence. Footsteps? Voices? Nothing.

The prisoners kicked open the door, and the first men left the basement. They went outside and didn’t see any vehicles, any soldiers. Slowly, one by one, people started going upstairs, outside. To breathe the springtime air. To look at the sky. Birds flew to the school for the first time in a month.

The bravest ones ran to their homes. They returned to the basement to tell the rest: They’re gone, they really are gone! People started to smile. Someone found a radio. They had to hear the news, to understand if Yahidne was now under the control of Ukraine or Russia. But there was only music on the radio. Then someone realized the song was in Ukrainian. It meant Ukraine was still free.

The day the Russians had entered the village, a few people had buried their phones in their barns and cellars. Now they dug them up. There were three hundred people but only a few phones: each got a few seconds to make a call. Svitlana tried to dial her husband, but she kept getting one number wrong. Finally, she called her daughter:

“Kristina!”

“Mom!”

Olha the agronomist went to look at her house. It hadn’t burned down, that was good. But the windows were broken, the roof destroyed, there were puddles inside. There was no electricity or gas. In the middle of the living room was a pile of things the Russian soldiers had thrown around while they rummaged through the wardrobes. They had stolen all the warm clothes, men’s shoes, socks, tools—it was the same in most houses.

“We all said that as soon as we got out, we wouldn’t step foot in that basement,” recalls Olha. But given the state of their homes, on their first night of freedom, most people returned to the place of their imprisonment.

That night, nobody locked them in. In the morning, the people went outside whenever they wanted. “My first morning of freedom,” Olha wrote in her diary. Out of habit, they boiled water and made breakfast. Then someone saw men in uniform coming out of the forest. The first reaction was to hide. But they looked closer and saw that it wasn’t a Russian uniform. Then someone shouted, “It’s our guys!”

The people ran up to the soldiers, touched them with trembling hands to check that they were real, laughed, and cried. They surrounded the soldiers and asked them for the news about the Russian retreat from the region, how the siege of Kyiv had failed, again and again, until the soldiers got tired of repeating it.

Svitlana and Lilia found a car and sped out of Yahidne. Many locals would follow. The Russians had mined some homes. People covered their windows in plastic to keep out the rain, got into buses, and went to relatives’ homes or temporary shelters. The most important thing was to get as far away as possible, find heat, comfort, and security.

That April in Yahidne, the only people working in the gardens were deminers.

When people returned, they began to repair their homes. They were still coughing from being in the basement, and chronic diseases got worse. But nobody rushed to see the psychiatrist who came to the village. “Nobody thinks they’re traumatized. People think they’re OK,” says Valeriy.

The school building remains a crime scene. The children attend school in the neighboring village. The yard has been cleaned up, but inside there are traces of the Russians everywhere—ration boxes, ashtrays, garbage. The soldiers left drawings on the walls, including the note “55 br”—55th Separate Motorized Brigade from the Tuva Republic. The names of nine soldiers were confirmed by the documents they left behind in Yahidne.

The regional administration wants to preserve the school as a war memorial. The writings on the walls will be important exhibits: children’s drawings, the words of the Ukrainian anthem in a child’s handwriting; the calendar that Valentyna Danilova drew with charcoal.

“If we were to die, other people will learn how much we endured,” Valentyna explains. This is why she kept these records.

Thanks largely to the testimonies collected from the villagers, 22 soldiers from the occupying brigade have been identified as suspects, according to Ukrainian prosecutors. By January 2023, four of them had been convicted in absentia by a Ukrainian court for violating laws and customs of war. Three were given 12 years in prison, and one 10 years. Their sentences are for the atrocities committed in Yahidne before March 5, before the villagers were forced into the basement. But there is a strong argument to hold Russian soldiers accountable for holding people in the basement too.

The Reckoning Project, an alliance of journalists and human-rights lawyers, says the Russian soldiers used humiliation and what is known in law as “torture, inhumane and degrading treatment” as a tactic to subdue the population in Yahidne. Systematic, widespread implementation of such ill treatment on a civilian population could be considered a crime against humanity.

The project’s legal analysts also note the absence of insignia on Russian soldiers’ uniforms, and concealing their identities from Yahidne residents, actions suggesting predetermination to commit atrocities. In other words—what happened at Yahidne was likely no accident. Like so many atrocities across Ukraine it was planned, deliberate, intentional.

Now comes the reckoning.

Oslavska is a journalist based in Ukraine. This story is published in partnership with The Reckoning Project, which brings together the power of storytelling and legal accountability to fight disinformation and impunity in Ukraine

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com