There’s a very good reason NASA planners chose Mars’s Gale Crater as the landing site for the Curiosity Rover when it touched down on the Red Planet in the summer of 2012. Gale Crater was once Gale Lake, a brimming body of water that could have given rise to microbial life in the first billion years of Martian history, before the planet lost most of its atmosphere and water to space. If you want to find clues to exobiology, a place like Gale is where to start looking. Now, as NASA reports, Gale Crater is proving itself to be an even more fertile spelunking spot than once believed.

While researchers have long known of the crater’s watery past, no one was ever certain of the depth of the water, or how long it persisted before the great drying began. To find that out, Curiosity has, since 2014, been painstakingly climbing Gale Crater’s Mount Sharp, a 5-km (3 mi.) tall peak in the center of the crater that serves as something of a geological history book. Mt. Sharp is made up of visible layers, with the oldest at the bottom, progressing to younger and younger layers as the mountain ascends. To drive up Mt. Sharp is to drive from Mars’s past, forward in time.

That fact serves as something of a marker for how long water was present on the planet, with the lowest parts of the mountain rich in hydrated salts like magnesium perchlorate, magnesium chlorate, and sodium perchlorate that are markers of a wet environment. The higher the rover goes, the drier things should get, with that chemistry giving way to sulfates—salts that form in much drier environments when, as NASA explains in its release, “water [on Mars] was drying to a trickle.”

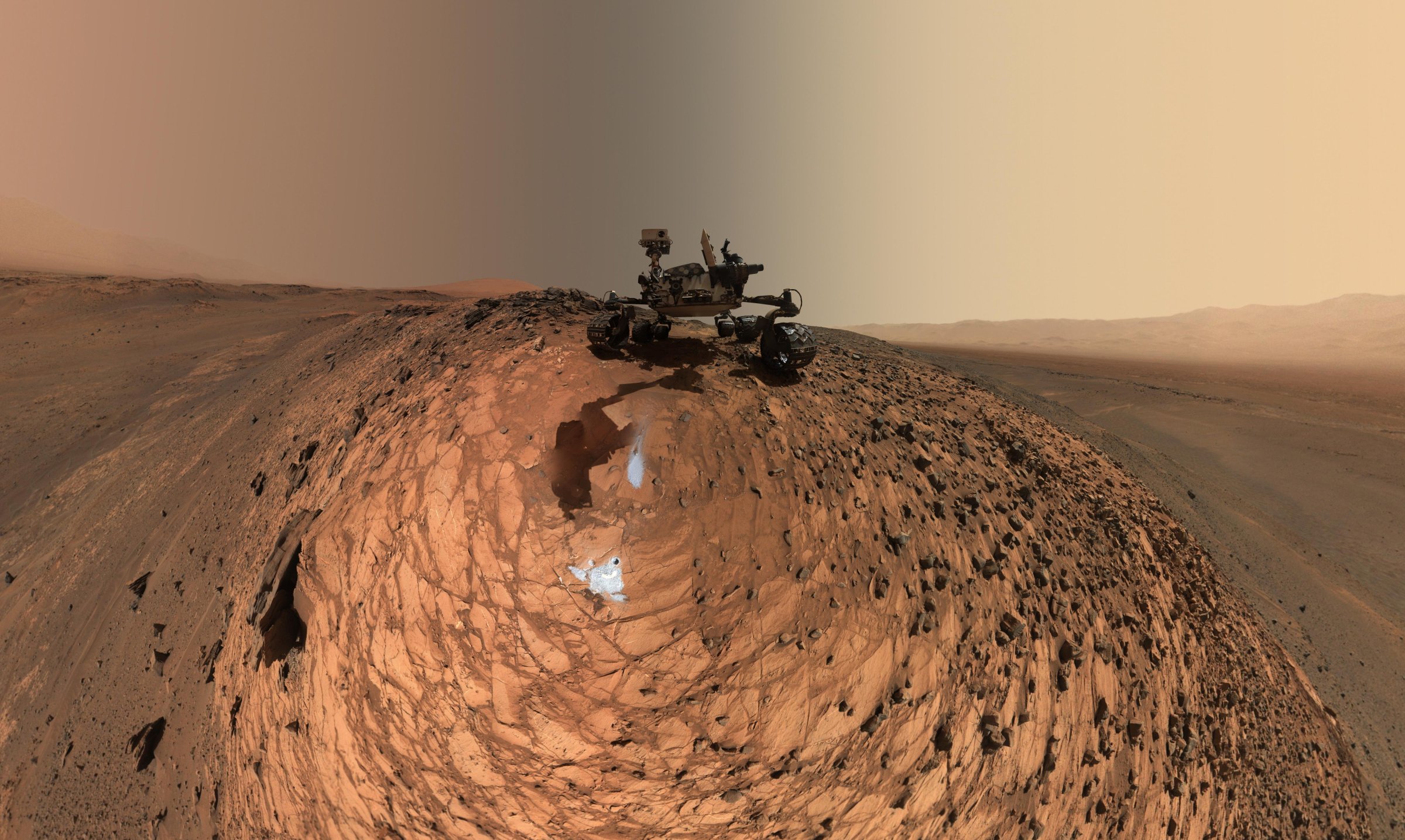

Curiosity’s most recent stop about half a mile up the mountain in a region thought to be rich in sulfates produced a surprise, however. All across the ancient rock at that elevated portion of the cliff face the rover found a rippling pattern, indicative of long ago surface waves that left their imprint on the once-soft sediment.

“This is the best evidence of water and waves that we’ve seen in the entire mission,” said Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity’s project scientist, in a statement. “We climbed through thousands of feet of lake deposits and never saw evidence like this—and now we found it in a place we expected to be dry.”

That’s not the only sign of water high up Mt. Sharp’s face. A channel running across the mountain at the same elevation is thought to have been carved by a powerful river. And at the base of the mountain lie telltale, car-sized boulders believed to have been shaken loose by the force of the flowing water. Mt. Sharp, clearly, was a much wetter formation, at a much higher elevation, than ever suspected. Curiosity’s next goal is to drill into the surrounding rock to sample its hydrated chemistry, better mapping the history of the mountain.

“The wave ripples [and] debris flows … tell us that the story of a wet-to-dry Mars wasn’t simple,” said Vasavada. “Mars’s ancient climate had a wonderful complexity to it, much like Earth’s.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com