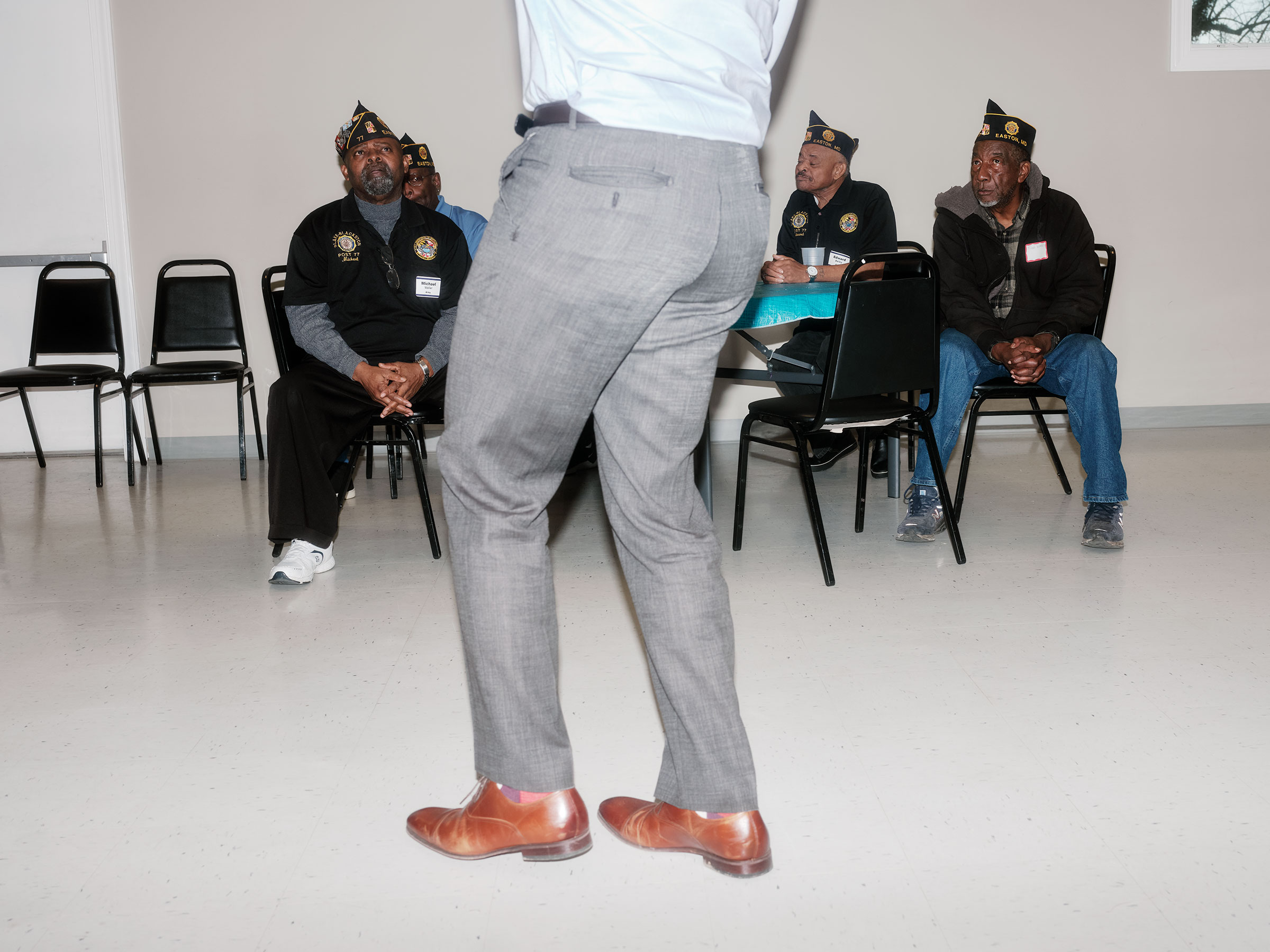

“Patriots,” Wes Moore says, pausing for effect. The room falls silent; the slot machines in the lobby are quiet. “I’m thankful that I’m in a room full of people who understand what that word means.”

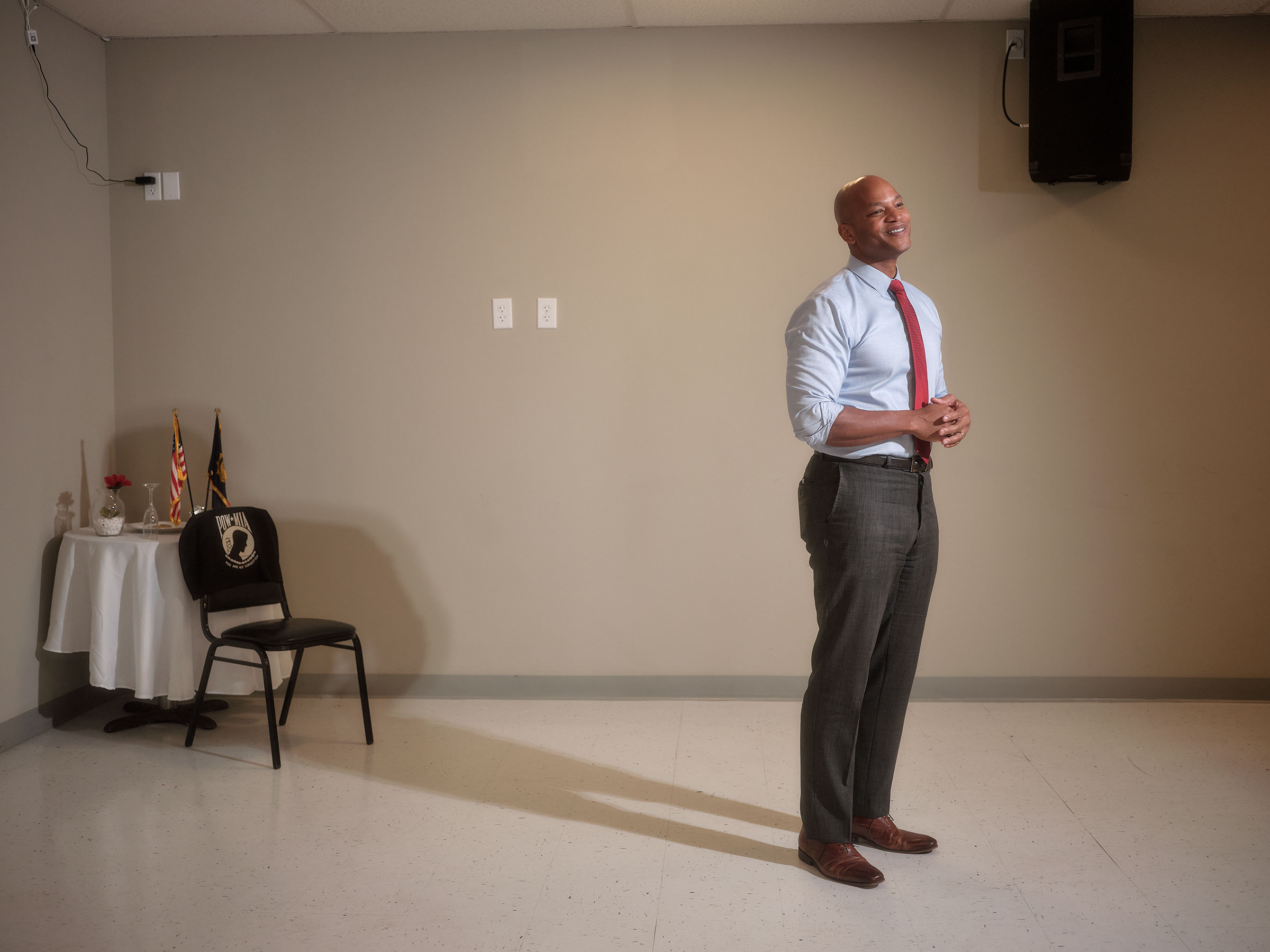

About 80 military veterans sit at plastic-clothed tables in front of a bar topped with metal buckets of Coors Light. It’s a chilly January night at an American Legion hall on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Moore is wearing a tie but no jacket, his bald head gleaming under the fluorescent lights. In a few days, the 44-year-old will be sworn in as Maryland’s first Black governor—the third elected in American history and the only one currently serving. Tonight he has come to this mostly red, mostly white swath of an otherwise very blue, very Black state to connect with his soon-to-be constituents. “Patriotism is not waving a flag around,” Moore says. “Patriotism is not telling our neighbors that we are better than them. Patriots—this is our time to get this right.”

Moore’s theme is both a product and a through line of a remarkable biography. Growing up fatherless and surrounded by violence, he turned his life around, graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Johns Hopkins University, and won a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford. He’s a decorated Army combat veteran, a best-selling author of inspirational memoirs, and a former Wall Street banker, small businessman, and nonprofit CEO. Just weeks into his first term in elected office, he is widely considered the Democrats’ most talented political newcomer since Barack Obama.

Headlines already speculate he’ll be the second Black President. The party’s leading figures clamor to associate themselves with him: President Biden held a rally with him right before the November election, and Obama himself cut an ad on Moore’s behalf. Representative Steny Hoyer, the former House majority leader, puts Moore in a category with Obama, Bill Clinton, and John F. Kennedy. “Wes lifts people up from their cynicism into their optimism and gives them a sense of the possible,” says Hoyer, who endorsed Moore and barnstormed his Maryland district for him despite planning to stay out of last year’s crowded gubernatorial primary.

For Democrats, the promise Moore represents can’t come too soon. The party’s stronger-than-expected midterms did little to quell its underlying angst: an aging cast of top leaders, a widening cultural gulf with working-class voters, and a brand yoked in the public mind to unpopular left-wing ideas. Biden’s own pollster, John Anzalone, warned Democrats in a post-midterm memo not to take too much credit for 2022’s successes, which were primarily the result of Republicans’ deficiencies. Liberal scholar Ruy Teixeira says many Democrats’ tendency to see the worst in America puts them at odds with the mainstream. “It’s very popular among large sectors of the left to talk about how fundamentally we’re a benighted country, white supremacist, bigoted and oppressive,” Teixeira says. “This just isn’t where most people are coming from. Most people are proud to be Americans.”

In the popular imagination, patriot is a right-wing term, redolent of camo, pickup trucks, and guns. To Moore, that’s an outrage. “I’m just truly offended when I hear people call themselves patriots whose definition is trying to destroy democracy,” he tells me. “What’s patriotic about trying to overturn elections? What’s patriotic about saying that your neighbors don’t deserve support? I’m not just confused by it. I’m amazingly bothered and pissed off by it. Because I know what patriotism is. I’ve seen it with my own eyes. I saw it with the paratroopers that I led in combat, people who were exemplifying bravery every single day.”

Moore is well acquainted with the case against America. His grandfather, born in South Carolina, fled the country as a child after Moore’s great-grandfather spoke out against racial injustice and was targeted for lynching. Moore’s own father may have been killed by racism—an educated, middle-class Black man whose medical complaint was dismissed by doctors, only for him to die in front of his 3-year-old son the next day. “I can tell you countless instances of this country’s history of brutality, of inequity, of heartlessness,” he says. “But if I do that without also talking about the other elements of its history, that’s a selective memory that I think is dangerous. Because what this country has meant to my family is that I can literally be the grandson of a man that the Ku Klux Klan ran out, and also, in the same breath, be a person who’s about to become the first Black governor in the history of the state. Both of those things are true. And we can’t look at one without understanding the other.”

As governor, Moore’s challenge goes beyond the normal tests posed by legislatures, agencies, and budgets. He’s trying to push his party in a new direction on some of its touchiest issues, change the conversation about national identity, and further his own political ambitions, whatever those may be, all at the same time. And he must do it in a moment when the post-racial future that Obama symbolized is a shattered illusion and the nation’s democratic system has been shaken to its core.

By reframing patriotism, Moore hopes to do more than just make a political pitch for himself and his party. It’s an unabashed plea for a new political culture, one in which we can dare to think of government as a shared enterprise and force for good, and politics as an avenue to achieve it. If he can love America, he suggests, anyone can; by believing in him, we can once again believe in this complicated and difficult nation, find a shared faith that bridges our bitter divides.

After his speech to the veterans, Moore gets few questions about political theory. Most audience members want to ask him about the difficulties of navigating the VA system, how they can get their benefits, what kind of services they deserve. Moore calls on a younger white vet in the back, a man in a hoodie and hunting cap who identifies himself as Chad Baker. Voice shaking, he describes a scary mental-health episode he experienced a few years ago: “a part of my life where death was the only way out.” Baker puts his hand over his face for a long moment before he can finish describing his ordeal—the lengths he had to go to for treatment, the local politician who offered no assistance.

Eventually Moore will answer Baker’s question, tell him he’s not alone, and promise to help. By the time he’s finished, audience members will be rising from their seats, asking not how they can be helped but how they can help Moore, pitch in for Maryland, sign up to volunteer. But at this moment, Moore says nothing. He strides to the back of the room, wraps Baker in his arms, and holds him as the man sobs, his burden lifted.

Moore has a way of seeming at home wherever he goes, and a recent morning in inner-city Baltimore is no exception. He steps out of his gleaming gubernatorial SUV looking like the spokesmodel for a wealth-management fund, flanked by suited men with sunglasses and earpieces. Around the corner, a line of people with ragged clothes and shopping carts wait for an unmarked door on the side of a building to open. When it does, Moore hands them bags of rolls and packs of raw chicken, dispensing hugs and autographs.

“I come from a family of preachers and teachers,” Moore says. They taught that “you have a moral obligation to commit to making this place better than the way that you found it.” He points to the “heroic” example of this community food bank’s proprietor, Arthur “Squeaky” Kirk, while lamenting that efforts like these are necessary: “They’re filling the holes of broken systems.”

Moore came to national attention in 2010 for his first book, The Other Wes Moore, a hybrid memoir meditating on an eerie coincidence: two Black boys with the same name, born into similar circumstances, whose lives took very different paths. Today, the other Moore is serving a life sentence for a jewelry-store armed robbery that left an off-duty police officer dead. He was sentenced in 2001, the same year Moore received the Rhodes.

After he returned from England, Moore began corresponding with and then visiting his inmate doppelganger. The book tells their stories in parallel, picking apart questions of agency, privilege, and fate along the way. “The chilling truth is that his story could have been my story,” Moore writes. “The tragedy is that my story could have been his.”

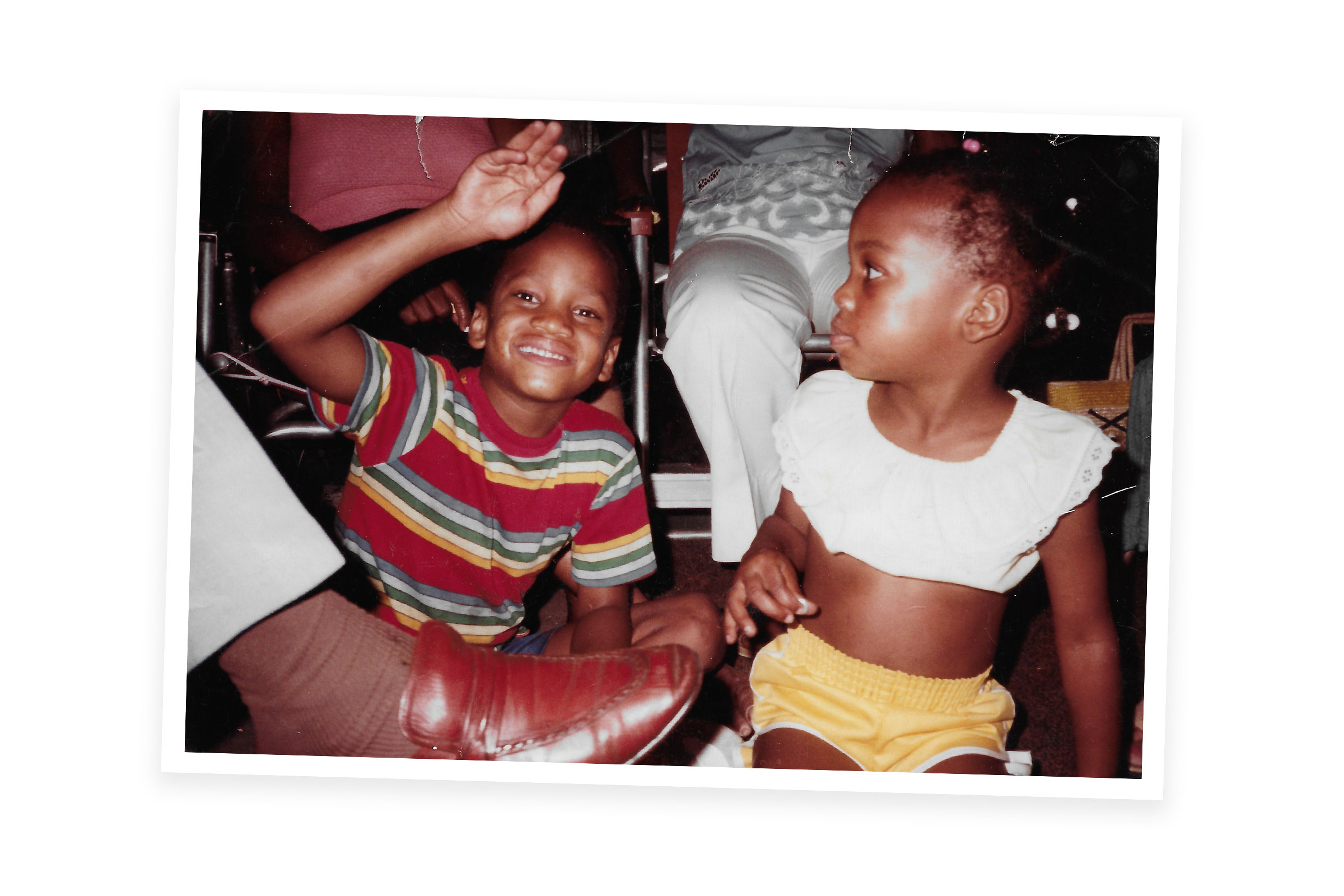

Moore was born in the liberal D.C. suburb of Takoma Park, Md. His father was a local journalist who met his mother, a Jamaican immigrant, when she came to work for his radio show. When young Westley was not quite 4, his father, feeling woozy and struggling to breathe, drove himself to the emergency room, where perplexed doctors asked the panicked, disheveled-looking Black man whether he might be exaggerating and sent him home with painkillers. He collapsed and died hours later of a rare but treatable condition, acute epiglottitis, that had swelled his airway shut.

Wes’s mother Joy moved him and his two sisters to the East Bronx to live with her Jamaican parents, a retired minister and elementary-school teacher. While Joy worked as a freelance writer and took odd jobs, the family pooled their resources to send Moore to the tony Riverdale Country School, hoping he could escape the neighborhood’s influence. But the neighborhood proved more powerful. “We grew up in a very challenging time in New York City,” says Moore’s childhood best friend, Justin Brandon, the only other Black boy in their third-grade class. “It was the birth of the hip-hop era, but also the crack epidemic, the Central Park Five—in retrospect, you realize you were exposed to a lot.”

A popular, mischievous kid, Moore started goofing off and hanging out with the wrong crowd. In middle school, he was caught writing graffiti and detained, but police let him off with a warning. He went right back to tagging, skipping school, and getting middling grades. When Riverdale finally threatened to suspend him, his family mortgaged their house to send him away to military school. It was a nerve-racking decision for his mother, who’d never even let her children play with toy guns, but she didn’t know what else to do. “I lost my husband to tragedy,” Joy Moore tells me. “I was going to do whatever I had to do not to lose my kids to the streets—or to mediocrity.”

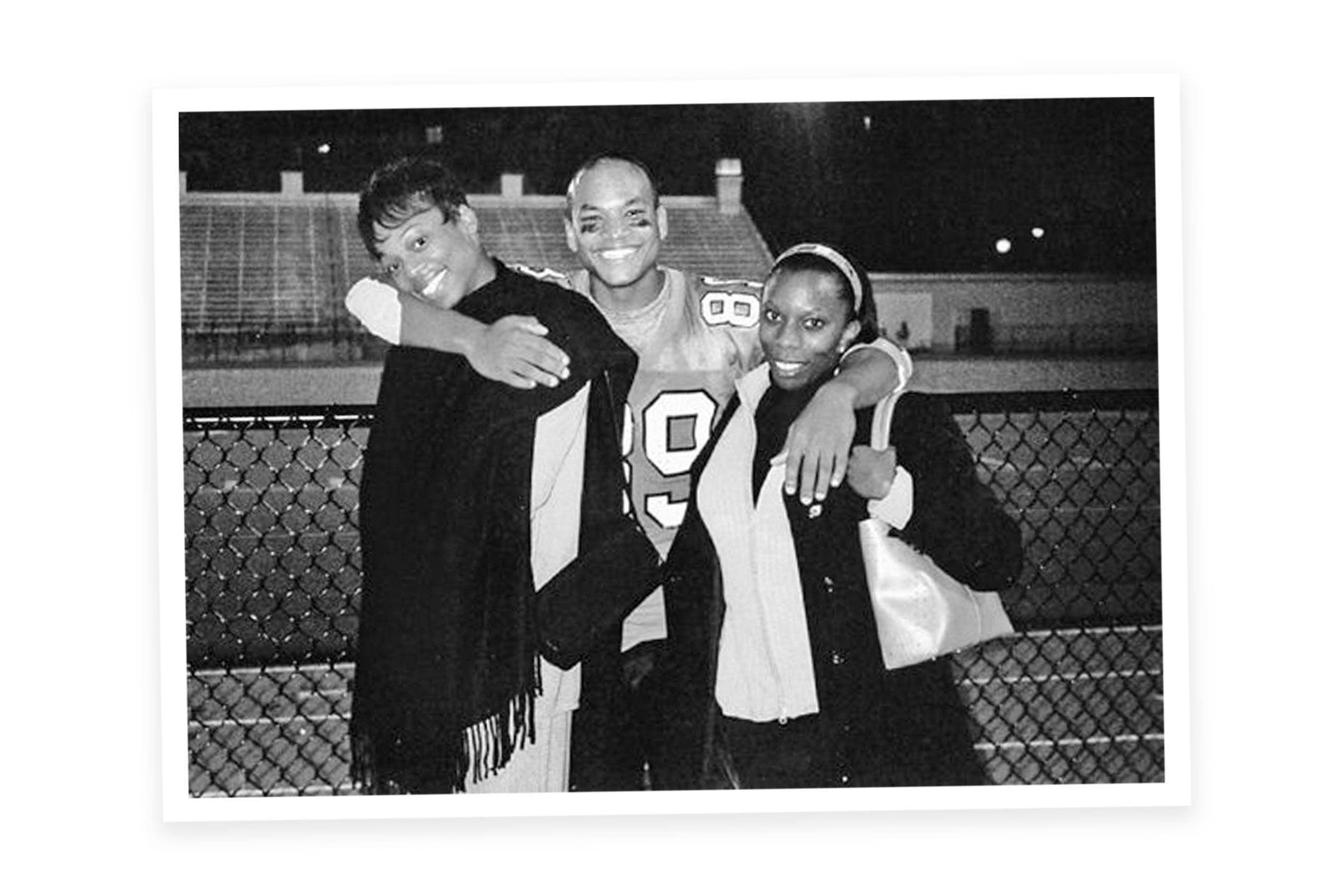

Moore initially resisted Valley Forge Military Academy outside Philadelphia, trying and failing to run away from campus. But once he committed to it, the school changed his life. He still counts earning the “cap shield” that marks the passage from plebe to cadet as “the hardest thing that I’ve done,” he tells me. “It was the first thing that I know I accomplished on my own—the first thing that I accomplished not because it was a giveaway or because someone felt bad for me or whatever. I earned that.” The feeling of accomplishment was intoxicating, he says, and he has spent the rest of his life chasing it.

Moore was on the football, basketball, track, and wrestling teams, served as student body president, and edited the school newspaper. Brandon recalls taking a bus from New York to see his friend compete in an oratory competition in suburban Philadelphia and being stunned by his command of the room. Moore’s speech was on the Constitution. “I am proud to be an American,” the teenager declared, “because I understand just what my ancestors had to go through in order for me to be called American.” He won the statewide contest.

Moore stayed at Valley Forge after finishing high school, accepting a commission in the Army and earning an associate’s degree at the school’s junior college. His mother moved back to the Baltimore suburbs for her job at a foundation for at-risk youth. Moore began spending time in the city and felt at home, he says. But he didn’t have a Baltimore address until he transferred to Johns Hopkins his junior year. That’s not necessarily the impression you’d get from The Other Wes Moore, which describes the two boys as growing up “at the same time, on the same streets, with the same name.”

In the book, Moore details his family’s various moves and accurately describes his birthplace as being “right on the border of Maryland and Washington, D.C.” But the fact that that border is some 30 miles from the Baltimore city limits—perhaps even farther, in psychic terms, from the West Baltimore projects occupied by his name-twin—would be lost on a reader unfamiliar with the region’s geography. After the book became a best seller, numerous interviewers introduced Moore as being from Baltimore as he nodded along without argument. A blurb on some editions of the book identified him as being born in Baltimore; the publisher now says this was an error Moore tried to correct.

During Moore’s gubernatorial campaign, an anonymous dossier highlighting these not-quite-discrepancies landed in the email inboxes of prominent Maryland Democrats, calling Moore and his story “completely fraudulent.” Moore’s campaign returned fire, tracing the dossier to a rival campaign and filing an election-board complaint. His loyalists see a sinister parallel with Obama: a successful Black man forced to produce his birth certificate to quiet a chorus of othering dog-whistles.

When I press Moore on his elisions, he grows animated. There’s a larger point, he says, that his critics are intentionally missing when they try to paint him as a son of privilege playacting as an inner-city kid. “When you ask people, ‘Where are you from?’ it’s an easy answer oftentimes,” he tells me. “It’s not for me. I moved around a lot when I was a kid—not because of choice, because of tragedy. I watched my father die in front of me, and my mother then is coming up in a home that she did not feel safe in.” His family’s economic precarity, and the danger of the Bronx streets, were real; if his family succeeded in going to great lengths to protect him from them, while the other Wes Moore lacked access to similar resources, that’s sort of the point. The other Moore also showed leadership potential, rising through the ranks of street-corner drug dealers and excelling in a job-training program. But he was in and out of jail, fathered multiple children as a teenager, and ran out of second chances.

Real, too, Moore says, was the sense of belonging he found in Baltimore when he began spending time there as a teen, hanging out with his sister and her school friends on breaks from Valley Forge. He interned twice for then mayor Kurt Schmoke, an early mentor who pushed him to apply for the Rhodes. “I finally get to a place that accepts me, flaws and all,” he says. “That became home, and it will always be home. So if people want to try to manipulate or attack my trauma for their political gain, then they can have that. But Baltimore as home is something that I am proud of.”

The question of home has always preoccupied Moore: what it means to be from a place; what we owe to the places we’re from, be it city, state, country, or planet. The Other Wes Moore and his subsequent memoir, The Work, reveal a searcher’s soul—a man transformed by the early realization that perhaps his life could matter when so many others would not.

Luke Bronin, a fellow Rhodes scholar who shared a house with Moore at Oxford, remembers the two of them sitting on the steps of the Bodleian Library at 1 a.m., discussing everything from the 9/11 attacks to criminal-justice reform. “Wes is one of those people who just have a gravitational pull, this energy you can feel,” says Bronin, currently the mayor of Hartford, Conn., “relentless optimism mixed with an intense sense of purpose.”

Colin Powell’s memoir My American Journey, the story of a Jamaican American from the Bronx who rises through the military to achieve political success, was Moore’s touchstone. Comparing it with The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Moore writes that Powell’s determined optimism resonated more with him than Malcolm’s revolutionary rage. Moore sympathizes with the long line of Black thinkers who’ve demanded “resistance to the American system,” he writes, but Powell “embraced the progress this nation made and the military’s role in helping that change to come about.”

Moore’s books can read like Oprah for the do-gooder set, full of feel-good parables about “changemakers.” He’s a curious storyteller with a restless earnestness—albeit one that never threatens to unsettle the power structure. Moore is self-aware about his natural glibness, and cites the “code-switching bonus” that gives him access to different worlds, from South African townships to corporate boardrooms, poverty-stricken neighborhoods to Islamist training camps. “The key to answering questions meant to get at who you are,” he writes, “was to first consider who the questioner wanted you to be.”

In 2005, Moore voluntarily deployed to Afghanistan with the 82nd Airborne Division. Returning to the U.S. after his yearlong deployment, he spent a year as a White House Fellow at the State Department, where his boss, Condoleezza Rice, remembers him as passionate, levelheaded, and nonideological. “I didn’t ever talk to him about it, but I would have been surprised if he didn’t have political ambitions, because he had the right package,” Rice tells me. “There was no doubt that politics was going to come after him if he didn’t come after politics.”

Moore spent a couple of years on Wall Street, learning numbers and budgets, but found the business world unfulfilling and quit Citibank at the height of the financial crisis. The gamble paid off. His books vaulted Moore into a career hosting shows on Winfrey’s OWN and giving paid speeches. In 2017, he became CEO of the Robin Hood Foundation, a New York–based nonprofit that aims to channel the resources of the city’s wealthiest into alleviating poverty. Colleagues there say Moore transformed the organization’s mission. He created a policy department and a “power fund” dedicated to funding organizations run by people of color. He also broadened the organization into other cities, including a pilot project in Baltimore, where his family continued to live. On the day I met with him on the Eastern Shore, Moore wore socks with lettering on the side reading, This Meeting Is Bull—t—a gift, he told me, from a Robin Hood colleague paying tribute to his preference for action over deliberation. In his four years as CEO, Moore raised $650 million for the organization.

In his role at Robin Hood, Moore testified before the Maryland general assembly in support of a plan to improve the state’s education system, forging a bond with the state’s first Black house speaker, Adrienne Jones, who became an early supporter and now will be a crucial ally to his governorship. Moore also pushed New York under then Governor Andrew Cuomo to expand the state’s child tax credit, lobbying hard to get the proposal included in Cuomo’s State of the State speech. “They didn’t use it, and I was frustrated,” Moore recalls. “And I remember having a conversation with one of my former colleagues, and they’re like, ‘We worked for six months to try to get them to include a line in the speech. But what if you could write the whole speech?’” That, he says, is why he decided it was time to make his run.

On Jan. 6, 2021, Oprah Winfrey was watching the Capitol riot unfold on television when Moore called to tell her he planned to run for governor of Maryland. “I said, ‘You want to run for governor in this political climate? Where everyone is so polarized?’” Winfrey recalled at his inauguration. “‘Look at what’s happening right now as we speak. You want to run in this climate?’ And he said, ‘Exactly.’”

Despite his minor celebrity, Moore was a political unknown in a state with a tight-knit political culture. In a field that included longtime state comptroller Peter Franchot and former U.S. Labor Secretary Tom Perez, critics cast the newcomer as inexperienced and vague on policy. Nastier currents flowed beneath the surface. In addition to the anonymous dossier questioning Moore’s biography, an email circulated alleging it would be too risky to nominate a Black man. “Three African-American males have run statewide for Governor and have lost,” Barbara Goldberg Goldman, a party donor who backed Perez, wrote to prominent Democrats. “This is a fact we must not ignore.” Both the Baltimore Sun and the Washington Post endorsed Perez.

Moore’s campaign positioned him as an outsider above grubby Annapolis horse trading. He emphasized economic opportunity—“work, wages, and wealth”—and took as his slogan the military-inspired “Leave no one behind.” For his running mate, he selected Aruna Miller, an Indian American state lawmaker from the suburbs. “It showed the state that we were going to be unafraid,” Moore tells me, ignoring the conventional wisdom that a white man from a rural part of the state would better “balance” the ticket.

Moore never led a public poll before the July primary. He won with 32% of the vote, beating Perez by 15,000 ballots. In the general election, few gave much of a chance to his opponent Dan Cox, a far-right GOP delegate who had hired buses to take people to the Jan. 6 protest in D.C. But Moore and Miller barnstormed the state seeking to run up the score, and won by a 2-to-1 ratio.

This isn’t necessarily as impressive as it sounds: Maryland is one of the most Democratic states in the country, and Moore’s margin over Cox was almost identical to Biden’s over Donald Trump in 2020. Still, the successive victories and high approval ratings of outgoing Republican governor Larry Hogan, who was term-limited in 2022, are proof the state isn’t a gimme for Democrats. “There is a substantial bloc of suburban, well-educated, middle-to-upper-income folks who are super tax-sensitive and instinctively inclined to believe that Democratic governors want to take their money and send it to poor jurisdictions to educate children not their own,” says former Democratic governor Martin O’Malley.

Beneath the surface of his unifying bromides, Moore has promised an agenda of sweeping liberal proposals, and vowed to move fast to get things done. Thanks in part to Hogan’s fiscal restraint and federal COVID-19 relief funds, the state is sitting on a $2 billion budget surplus. On Jan. 20, Moore released his first budget, a $63 billion proposal to raise the minimum wage, increase tax credits for immigrants and childcare, and boost state spending on education and transportation without raising taxes. It would create a new state department to work on Moore’s signature plan, a voluntary year of service available to every high school graduate.

Hogan frequently clashed with or ignored Maryland’s liberal legislature. Moore’s challenge may be the opposite: reining his party in. O’Malley recalls the best advice he got from a more senior pol before taking office: Look in a mirror and practice saying no. For a people pleaser like Moore, this may not come naturally. He wouldn’t be the first promising newcomer to be stymied by the messy, slow-moving machinations of government.

What does it mean to love America today, and what would it take for Moore to lead a new charge for Democrats? Ruy Teixeira, the liberal scholar, says merely saying the word patriotism means little if the party isn’t willing to stiff-arm its activist base on hotly charged issues like whether children should get gender-reassignment surgery or criminals should be detained before trial. “People in a lot of the rest of the country look at the cultural concerns of liberal elites in big metropolitan areas and they’re like, ‘What the f-ck are these people talking about?’” says Teixeira, who left the liberal Center for American Progress last year for the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute because he didn’t feel he could tell the truth about progressives’ unpopular approach to race, gender, and country, and co-authors a newsletter called The Liberal Patriot.

When I ask Moore whether he believes America is a racist country, he doesn’t give a yes-or-no answer. “You can’t look at the history of this nation without understanding that race has underscored everything in this country from its origins,” he says. It’s impossible for him to speak at the Maryland statehouse, he notes, without being conscious that it was built by enslaved people. The recent death of Tyre Nichols, the 29-year-old Black man beaten to death by Memphis police, only highlights the need to tackle injustice head-on, Moore tells me: “If we’re not going to take accountability seriously, we’ll just keep on dealing with the aftermath.”

Black Americans have always faced the double bind of having their loyalty questioned in the face of brutal oppression. In the face of slavery and Jim Crow, it would be easy to sympathize with the Rev. Jeremiah Wright’s impolitic plea for God to damn America—but if they do, they’re tarred as traitors. When Moore’s great-grandfather, a Howard graduate and Presbyterian minister, left South Carolina in the dead of night and took his family back to Jamaica, he vowed never to return. But Moore’s grandfather came back as a young adult because he viewed America as his birthright. “He said this was his country, and he would not be chased out of it,” Joy Moore says. As Wes Moore puts it, “I grew up in a family of people who loved this country, even if it didn’t always love them back.”

Moore’s invocation of patriotism often calls back to his Army service. But being a patriot shouldn’t have to mean that Democrats support the military-industrial complex or give up the fight for social justice, says former Maryland Congresswoman Donna Edwards, a Black progressive. “I grew up in a military family, and I think for too long national Democrats have been reluctant to talk in those terms,” Edwards says. “I voted against defense authorization bills. I voted against the war in Iraq. There’s no reason Democrats can’t identify proudly as patriots and still work to change and improve the country.”

Asked if he wants to be President, Moore doesn’t equivocate: “No.” But that hasn’t stopped national Democrats from buzzing about his prospects. The comparisons with Obama are as instructive as they are inescapable: two fatherless Black men with sparkling résumés who built a political brand on memoirs that grappled with their complicated identities. (Obama, too, was dogged by a publishing error that gave ammunition to his haters, a 1991 promotional bio that wrongly said he was born in Kenya and helped spark the racist birther theory.) Both staked their mass appeal on a message of healing political divides—reclaiming a United States of America from our patchwork of red and blue.

In the aftermath of Trump and George Floyd, that seems less possible than ever, and Moore doesn’t pretend otherwise. Instead, he looks our collective pain in the face, refuses to be defeated by it, and presents his own love of country as the reassuring embrace that can knit us back together. “I walk through life with an understanding of this country’s inequities and its history,” he says. “But I also walk through life with a hope of the promise that this country has offered to some, that we want to make sure that it offers to all. That was the foundation that this country was built on. That was its promise. That was its hope. And so I’m simply asking this country to live up to its ideals.”

The sun is going down on the Eastern Shore, and the Legion hall has emptied out. For all his sunniness, Moore is not exactly sanguine about the state of things. “I think we’re in pretty bad shape,” he says. “It’s not just that we’ve watched how the rhetoric has been pitched up, even more incidents of political violence, antisemitism, homophobia, racism, etc. It’s that we’ve stopped communicating. We’ve stopped actually speaking to one another. We’re more than happy retreating to our corners. And I think it’s leaving a lot of people very frustrated and stranded and angry and afraid.”

The forces that propelled Trump—forces Moore sees as a continuation of the ones that drove his grandfather from the country—haven’t been defeated. “People have to understand how dangerous this entire movement is,” he says. “It just means that our pushback has got to be that much more aggressive, that much more thorough, and that much more loving. Because I don’t think that you are going to be able to defeat this thing simply by calling it bad. You’ve got to defeat it by also offering an alternative.”

Moore speaks of himself as a receptacle into which his ancestors’ hopes and dreams have been “poured,” their sacrifices and struggles carrying forward through the generations. “The police officers and the firefighters and the teachers, or the engineers or the custodians, or whoever it is who are working every day to make other people’s lives better—those are patriots,” he says. “They didn’t believe in tearing down things. They believed that we actually had a moral obligation to make things better than the way we found it. Not to light things on fire and walk away as the flames were igniting behind you. That’s not patriotism. I want to remind people: let’s not forget what we’re fighting for.”

With reporting by Julia Zorthian

Correction, Feb. 14:

The original version of this story misstated the neighborhood Wes Moore moved to as a child. It was the East Bronx, not the South Bronx.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Molly Ball/Easton, Md. at molly.ball@time.com