The fight for democracy has been one of the most defining narratives of 2022. It featured in the U.S. midterms, the first electoral contest to take place since former President Donald Trump’s false claims that the 2016 presidential election was stolen. It was central to major elections in Hungary and Brazil, where incumbents suggested, without evidence, that the vote would be undermined by voter fraud and international interference.

But perhaps nowhere has the fight been more pronounced than in Ukraine, where the ongoing Russian invasion has come to represent the front-line of the global battle between the forces of democracy and authoritarianism. “They see the democracy and freedom of Ukraine as a question of their own survival,” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky told TIME’s Simon Shuster, referring to the Kremlin. “If they devour us, the sun in your sky will get dimmer.”

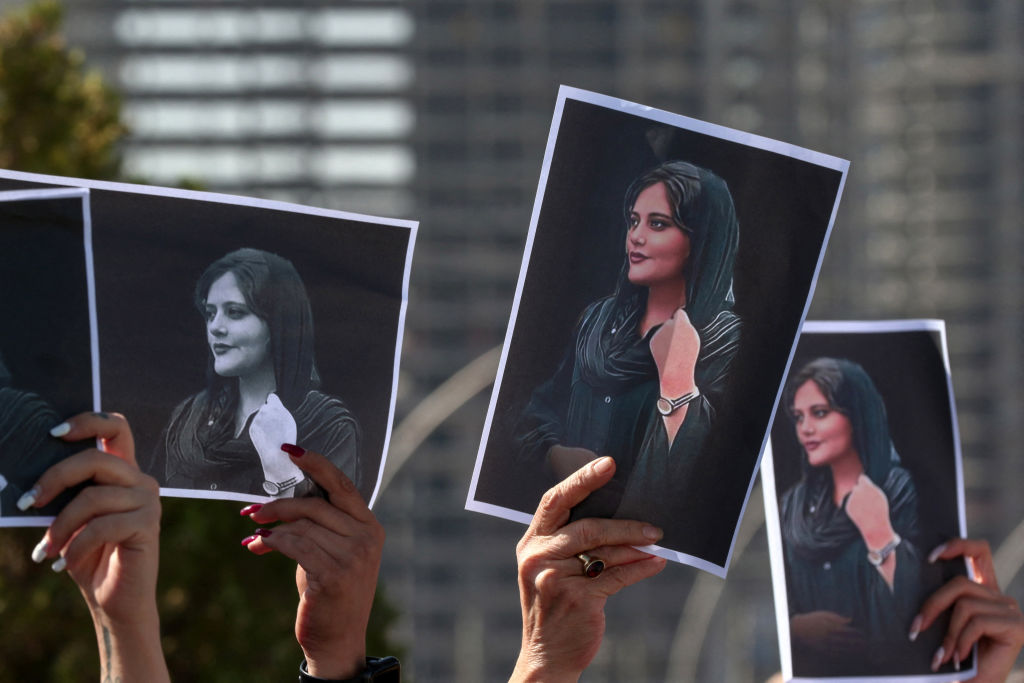

While Ukraine’s fortitude continues to be seen as a source of optimism about democracy’s strength, the world’s skies are already much dimmer than they used to be. Democracy in 2022 has been under siege, marked by attempted coups in Peru, contested elections in Brazil, and authoritarian crackdowns on peaceful protesters in Iran, China, and elsewhere. According to an annual report on the state of global democracy by the Stockholm-based International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, or International IDEA, half of the world’s democratic nations are in retreat. The most concerning cases can be found among the world’s biggest and most influential democracies, such as India, Brazil, and the United States.

Read More: Women of Iran: Heroes of the Year 2022

Below, what you need to know about how democracy fared in 2022.

How is democracy doing globally?

The short answer is “not well,” says Kevin Casas-Zamora, the former Costa Rican politician who now serves as secretary general of International IDEA. Since the organization started tracking democracy worldwide in 2017, it has found that the number of countries moving toward authoritarianism are more than double those that are moving toward democracy. Of the 104 democracies included in the study, 52 are considered to be eroding, up from 12 a decade ago. Among non-democratic countries such as Afghanistan and Belarus, nearly half are becoming more repressive.

“Democratic erosion affected 12% of democracies a decade ago,” says Casas-Zamora. “That proportion has gone up to 50% now.”

The extent of the erosion varies by region. In Europe, for example, democracy remains stagnant, with nearly half of its democracies having suffered erosion in the last five years, according to International IDEA. In the Asia-Pacific region, just over half (54%) of people live in democracies, the vast majority (85%) of which are considered weak or backsliding. The Americas, meanwhile, is home to three out of seven backsliding countries.

This democratic erosion coincides with another worrying trend: that the number of people who have faith in democratic systems to deal with the most pressing issues of the day—including rising food and energy prices, ballooning inflation, and recession—is steadily shrinking. Studies show that satisfaction with the democratic process around the world has suffered a notable decrease in recent years. Some 52% of people across 77 countries agreed that having a strong leader unbeholden to legislatures or elections is a good thing compared to 38% in 2009, International IDEA’s report said, citing a 2021 study by the World Values Survey.

What constitutes democratic “backsliding”?

Democratic backsliding, or “autocratization,” denotes an erosion of the norms and institutions that underpin democratic systems. While backsliding can be spurred by a major event such as a military coup, it can also be brought on at the hands of democratically-elected governments that, once in power, choose to subvert the basic tenets of democracy that enabled them to get elected in the first place. “That kind of democratic backsliding has become a sort of pandemic in its own right,” says Casas-Zamora, referencing “severely backsliding” countries such as Brazil and Hungary, both of which have seen their democratic institutions undermined by illiberal leaders Jair Bolsonaro and Viktor Orbán, respectively. India and the U.S., which have also seen their democracies tested in recent years, are classified by IDEA as “moderately backsliding.”

While the methodologies used to identify backsliding countries vary across organizations, in IDEA’s case, whether a country is deemed to be backsliding is determined by a number of variables, including the effectiveness of its institutions (can the state hold credible and regular elections?), its checks and balances (are there controls on executive power?), and how it safeguards fundamental rights (are civil liberties protected?). IDEA also takes into account other indicators such as impartial administration (is corruption an issue?) and civic participation (are citizens engaged beyond elections?).

While these indicators are useful in assessing the health of democracies, “The way in which democracy is ailing varies from country to country,” says Casas-Zamora. “A single score ranking the countries would probably obscure much more than it would clarify.”

Why is democracy in retreat?

While there is no singular cause of the democratic erosion taking place around the world, there are thought to be a number of common challenges. Among the most talked about is the rise of heightened political polarization, fueled in part by the rise in populist-style “us versus them” politics. That polarization has been stark in the U.S., where it has resulted in gridlocked politics, heightened distrust in democratic institutions, and even political violence. Other notable causes include increasing distrust in the legitimacy of elections and widespread disillusionment in mainstream political parties.

But another, perhaps more fundamental cause is rising levels of inequality. “Democracy ultimately is a system predicated on a notion of equality between citizens,” says Casas-Zamora, “The grotesque levels of inequality that we are seeing, and that the pandemic made worse, go against the ethos of democracy.”

What can be done to strengthen democracy?

Apart from reducing inequality, one of the most important things that countries can do to stave off democratic backsliding is to ensure that its checks on executive power—including institutions such as the judiciary, the free press, and civil society—are safeguarded. For democracies, this also means ensuring that the credibility of its elections, the most important check on power in any democracy, is preserved.

“We are seeing not just transnational campaigns to subvert the legitimacy of electoral results all over the world, but also in many places we are seeing credible, competent, and autonomous electoral management bodies coming under political fire,” says Casas-Zamora, pointing to recent examples of election denial in Brazil and the U.S. “This is about playing defense.”

But democracies must also play offense, particularly when it comes to making the case for the democratic model as a superior form of governance. Casas-Zamora says leaders can do this in part by experimenting with new forms of civic engagement, such as citizens assemblies. They also need to be able to demonstrate that democracy is capable of solving the concrete problems that people face. “For 99% of people out there, the proof of the pie is in the eating,” he says. “We have to embrace, in a very conscious way, a very vigorous agenda to improve the quality of democratic governance, and that means we have to revisit questions of institutional design—how we design our democracies to be better able to make decisions and implement decisions in an efficacious way.”

Is there any causes for optimism?

While the state of global democracy is bleak, one of the few bright spots is the prevalence of civic action around the world, from the international demonstrations raising awareness about the climate crisis to mass protests in repressive regimes such as Iran and China.

Read More: ‘Not What You’d Expect in a Democracy.’ How Britain Is Waging War Against Climate Protesters.

“The number of social movements, the number of demonstrations, people going out in the street to demand their rights, is really extraordinary,” says Casas-Zamora. “People are willing, at an enormous risk, to go out on the street to demand their rights. This is a positive story.”

What can we expect in 2023?

If the trends are any indication, it’s that the acute challenges facing democracy are not going away.

“The next few years are going to be extraordinarily challenging for democracy and we’re going to see a lot of people on the street,” says Casas-Zamora. “This is a double-edged sword, because on the one hand this can create a lot of political instability; on the other hand, it’s also an exercise of democratic rights. It will create a lot of instability but it will also prove the willingness of people to demand their rights, which is not a bad thing.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Yasmeen Serhan at yasmeen.serhan@time.com