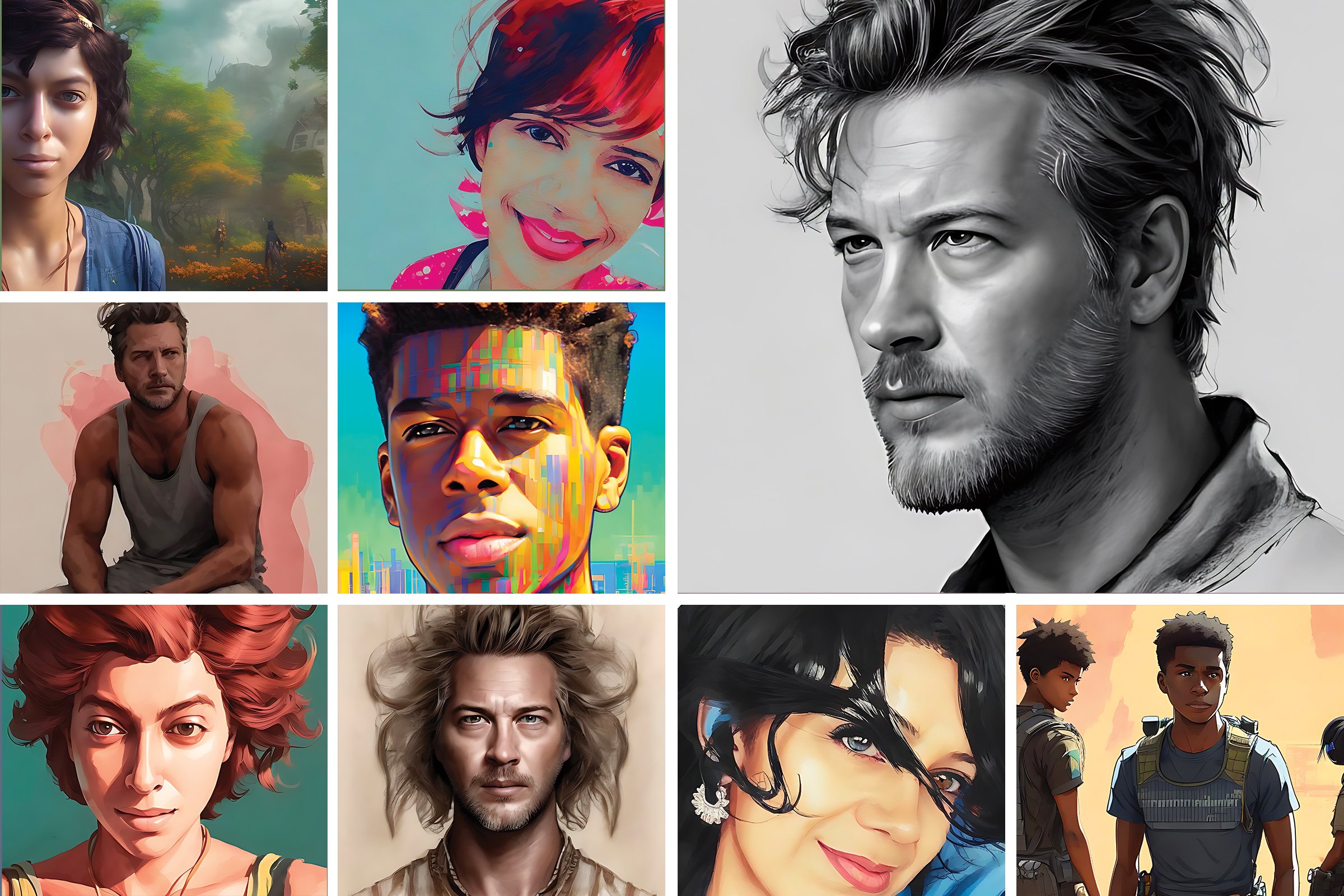

If you’ve noticed an influx of illustrated selfies—depicting people as fairy princesses, astronauts, and anime characters—popping up across social media in recent weeks, you’re not alone. These AI-generated images are the product of digital editing app Lensa’s new “Magic Avatars” feature, a tool that uses machine learning to create stylized portraits based on photos provided by users.

Lensa has been around since 2018, but started skyrocketing in popularity when Magic Avatars launched in late November. The app saw around 13.5 million worldwide installs in the first 12 days of December, more than six times the 2 million it saw in November, according to analytics firm Sensor Tower. Consumers also spent approximately $29.3 million in the app during that 12-day period, Sensor Towers reports.

Lensa’s digital illustrations have clearly struck a chord with people. But what is it about this AI tech that has users so hooked?

More from TIME

How does Lensa AI work?

When you download Lensa, you get a seven-day free trial and then have the option of paying a one-time fee for a specific number of unique avatars ($3.99 for 50 is the cheapest option) or shelling out $35.99 for an annual subscription and unlimited avatars. The app then uses an open-source neural network model called Stable Diffusion that’s “trained on a sizable set of internet data to generate images from…small pieces of text describing the desired scene in the output image,” according to Prisma Labs, the company behind Lensa.

Basically, it uses AI technology to render photos into artwork based on text prompts. With Magic Avatars, these prompts are categories like cosmic, fantasy, and pop.

The psychology behind Lensa AI

While there are layers to Lensa’s appeal, there’s likely a vanity factor in play, says Nick Yee, a social scientist who has been researching self-representation and social interaction in gaming and virtual worlds for over two decades. It’s no secret that people like to see pictures of themselves looking good. But, experts note, Lensa’s appeal shines a spotlight on just how complicated the idea of “looking good” can be.

“A lot of these apps are trained on models who are ‘attractive,’ who have slimmer bodies, who conform to ideals of beauty in our culture,” he says. “So sure, Magic Avatars is putting your photo in these fantastic scenarios and dressing up your portrait. But along the way, it’s also making a photo of you more ‘attractive.’ That’s something a lot of people pick up on when they see their friends try it out.”

Some people do get a short-term confidence boost from seeing themselves that way, says Rabindra Ratan, an associate professor at Michigan State University’s Department of Media and Information who researches the effects of human-technology interaction.

“What we consistently find is that a small boost in ‘attractiveness’ in your avatar is good for your confidence,” he says. “It doesn’t make you feel deceptive. It makes you feel like your good traits are just a tad bit magnified.”

But there’s also a flip side to this effect. “If that boost is too great, then it’s harmful and problematic for a host of reasons,” Ratan says.

In addition to reigniting debate over the ethics of AI art and data-privacy issues, Lensa has sparked controversy over how its “magic” AI portraits depict women and people of color.

“One common critique I hear is that the app typically makes you look younger and makes you look thinner and makes your skin whiter,” Yee says. “And depending on your face, some of those effects could be exaggerated to the point where it becomes unrealistic and you get this backlash effect of, ‘This is clearly not me.'”

In an FAQ addressing questions and concerns that have been raised about its tech, Prisma said Lensa’s model was “trained on unfiltered Internet content. So it reflects the biases humans incorporate into the images they produce. Creators acknowledge the possibility of societal biases. So do we.”

So, depending how close your face is to the average in the trained model, people can come away from using the app experiencing very different psychological effects, Yee says.

“For people who are Caucasian, who are younger, and who are similar to the model’s trained norms, you’re more likely to get that confidence boost because the output is close to what you look like; there’s a strong resemblance, but there are improvements,” he says. “Whereas if you’re an ethnic minority, you have an atypical facial structure, you’re older, or your skin is darker, you’re more likely to get those backlash effects.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Megan McCluskey at megan.mccluskey@time.com