The Underground Railroad ran straight through Philadelphia. Each year, hundreds of fugitives passed through the city, seeking refuge from the slave catchers who pursued them. Once they arrived in the City of Brotherly Love, however, most knew they were not yet safe. They needed to keep moving, traveling on to places where they might be more secure, perhaps to New England, or better yet, all the way to Canada. By the 1850s, a network of activists had come together in order to help such fugitive slaves—to help them get to Philadelphia and to help them move on safely. At the center of this network was William Still.

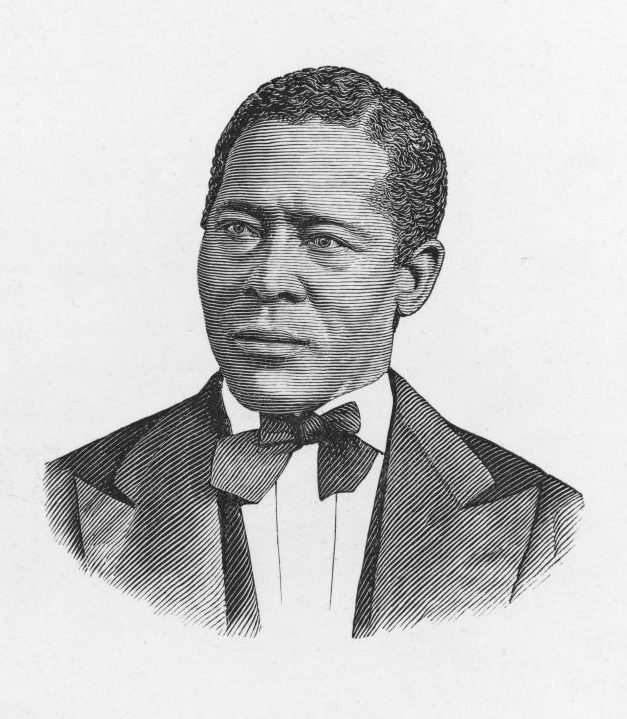

Still was the most important figure in this critical portion of the Underground Railroad, during the period when the network was more important and visible than ever before, and yet we know far less about him than we should. In contrast to his far better-known co-worker, Harriett Tubman, who famously traveled into her native Maryland over and over in order to guide others to freedom, Still’s work seems less dramatic. It was, however, no less important. Still devoted himself to supporting “agents” like Tubman, and to assisting the fugitive slaves—men, women, and children—who were themselves the true engine of the Underground Railroad.

Still was born free, in the free state of New Jersey, the youngest of 18 children. His parents had been enslaved on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Levin Steel, William’s father, was able to purchase his freedom after years of saving. When his wife, Sydney, was unable to do the same, she fled, taking with her the couple’s four children. She joined her husband in New Jersey, but before long they were tracked down by slave hunters and dragged back to Maryland. When Sydney fled a second time, she made the heartbreaking decision to leave behind her two eldest children, Levin, Jr. and Peter, knowing that she likely would never see them again.

Taking the name “Still,” the family settled in rural South Jersey where they hoped to make a new life for themselves as free people, and where they hoped to evade the long reach of slavery. They never forgot the boys that had been left behind, and when William was born in 1821, it was into a family that was acutely aware of its connection to slavery, a family that felt an obligation to help others in their flight from bondage. As a young boy, Still and other family members aided fugitive slaves—hiding them from slave catchers, and guiding them to freedom.

Eventually, like many young men, William Still left his rural home behind and moved to Philadelphia. There, Still quickly immersed himself in the city’s vibrant free Black community. He found work at the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, an interracial organization where he was able to continue his efforts in service to fugitives from slavery.

Read more: What You Still Don’t Know About Abolitionists

Still also became the chairman of Philadelphia’s Vigilance Committee, an organization loosely affiliated with the Anti-Slavery Society, which sought to aid fugitive slaves by any and all means necessary. The committee coordinated with friendly ship captains, who sometimes secreted away passengers in cities like Richmond and Norfolk and provided them safe, if not comfortable, passage to the North. It maintained connections with allies in neighboring towns like Wilmington, Delaware, or Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, who would meet fugitives and send them on to Still. When fugitives arrived in Philadelphia, members of the committee helped hide them (often in Still’s home) and then usually provided them with a means of traveling on. Most often this meant a train ticket. The committee sometimes provided new clothes for fugitives; it paid to bathe and shave fugitives to make them less conspicuous. The group offered food and comfort to those who had known little of this on their flight from bondage. It gathered information, always seeking to stay one step ahead of the slave catchers who roamed the streets of Northern cities and towns searching for fugitive slaves. At times it mobilized the Black community of Philadelphia and beyond to protect fugitives with physical force. To make all of this possible, the committee also raised money, with public events and private solicitations. Still’s organization received support from as far away as Great Britain.

This was the work that Still did, day in and day out, but his position at the center of this vast abolitionist network also involved him in some of the most dramatic events of the era. When Henry Brown mailed himself in a box in order to escape slavery, Still was one of the men who was there to open that box in Philadelphia. When slave catchers threatened the safety of a group of fugitive slaves in Christiana, Pennsylvania, Still received intelligence of the plans of these slave catchers and passed it along to allies who were able to successfully drive off the slave hunters. When the white abolitionist John Brown was planning his assault on Harper’s Ferry, he sought Still’s advice and hoped to enlist Still in the effort.

Much of Still’s work was necessarily clandestine, but he gradually took on a more public role in the abolitionist movement, becoming one of the public faces of the Underground Railroad. Carefully chosen publicity, revealing just enough tantalizing detail, could help the Vigilance Committee raise money and rally the morale of abolitionists in the face of the many daunting setbacks of the 1850s. “The Underground Railroad cause is increasing,” boasted Still in an 1856 newspaper article, “they cannot stop the cars.” Whatever the daily challenges abolitionists faced, Still reminded his allies that their cause was righteous and that it would triumph.

Eventually, as the conflict over slavery erupted into the Civil War, Still stepped down from his position at the Anti-Slavery Society and the Vigilance Committee, but he never ceased his service to the cause of Black freedom. Still established a prosperous coal business, which would make him one of the wealthiest Black men in Philadelphia, but he also devoted himself to the civil rights struggles of his day. In particular, he challenged the segregation of the streetcars of Philadelphia. Still also supported the push for extending to Black men the right to vote, a right that Pennsylvania had denied them since 1838. His business success also allowed him to expand his philanthropy to support the poorest and neediest of the Black community in his adopted city and across the country.

It had been his work on the Underground Railroad, however, that had brought Still to prominence. Even after he left his formal role at the Anti-Slavery Society, he continued to share stories of his work with the Vigilance Committee. Still had always kept meticulous records of this work. Doing so was dangerous; if they had fallen into the wrong hands, countless fugitives and their supporters would have been put at risk—at one point Still hid his records in a cemetery for safekeeping. He knew, though, that these records, and the stories behind them, had power. He had kept them in order to make sure that fugitive slaves and their families might have some means of reuniting.

Eventually, he realized that these stories might also serve another purpose. In the decades after the Civil War, many white Americans had come to embrace a memory of the war that celebrated how the bloodshed of white soldiers on both sides could ultimately bring the nation back together. This emphasis on the shared sacrifice of white soldiers not only ignored the ideological context of the war—the reasons men fought in the first place—but it also denied the critical role played by the hundreds of thousands of Black soldiers and sailors who fought for the Union. Similarly, in the hands of white historians, the Underground Railroad had come to be depicted as a network almost entirely composed of kindly and courageous white people. Fugitives themselves appeared largely as the helpless beneficiaries of white bravery. Still always acknowledged the importance of white supporters, but his records and memories showed that this was not the whole story. Still was determined that this whole story be told.

In 1872, Still published the fruits of that determination. The Underground Railroad is nearly 800 pages, packed with reminiscences, letters, scraps of newspaper, and biographical sketches. It vividly captures the cruelty of slavery and the heroism of those who fled from it. Still made sure that his readers understood that fugitives themselves, not those who came to their aid, were at the heart of the story of the Underground Railroad. The book is a fitting legacy of Still’s life work, and today, as we look back on the life of William Still, more than 200 years after his birth, those stories retain their power. They remind us of the hundreds of men, women, and children who sought freedom by fleeing to Philadelphia in the 1850s and of Still’s critical role in ensuring that they succeeded.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com