For six long years, Donald Trump has been at war with the FBI. During the 2016 campaign, he complained of foot-dragging in the Hillary Clinton email investigation, demanding that the bureau “lock her up” without supporting evidence. Once he became president, he asked for unswerving loyalty from FBI director James Comey, only to fire Comey three months later for insufficient obedience. Since then, we have been through the Russia inquiry, the Mueller Report, the January 6 investigation and the Mar-A-Lago raid, none of which have improved the situation. In November, the Republican members of the House Judiciary Committee issued a 1,000-page report complaining that the FBI has become “politicized” beyond recognition. They’ve hinted at a sweeping investigation of what they claim is the FBI’s anti-Republican and anti-Trump bias as they retake the House.

The ferocity of this back-and-forth reflects our hyperpartisan times, when apparently nothing—not the law and certainly not the facts—seems to rise above the political fray. But tension with the White House, and with political candidates, is also part of the FBI’s history. In theory, the bureau is supposed to be a non-partisan government body, loyal to the constitution, the public, and the truth. In reality, it has often been drawn into highly politicized investigations in which it is impossible to satisfy all concerned.

Nobody understood the tension between the FBI’s non-partisan mission and its enmeshment in politics better than J. Edgar Hoover, who spent much of his 48-year reign as FBI director trying alternately to accommodate, resist, and avoid the demands of political men. Hoover served under eight presidents: four Republicans and four Democrats. In order to pull off that feat, he often needed to play the Washington game even as he insisted he was a purely professional career bureaucrat. Today, we tend to think of Hoover as a one-dimensional villain, a man who used his enormous influence and staying power toward nefarious ends. But that power also gave him the ability to resist certain kinds of political pressure—and to live to tell the tale.

As a young man, Hoover witnessed up close what could go wrong when the Justice Department got too close to partisan politics. In 1921, President Warren Harding appointed his campaign manager, Harry Daugherty, as attorney general, and Daugherty appointed a swashbuckling private detective named William J. Burns to run the Bureau of Investigation (forerunner of today’s FBI). All three men came out of the formidable Ohio Republican machine, which had produced six of the previous eleven presidents. Daugherty made no secret of his plan to use the Justice Department to serve their private and partisan purposes. The stories became legend: poker games at the White House, secret liquor stashes, and open bribes, plus federal raids on senators who asked too many questions. As assistant director of the bureau, Hoover had a front-row seat to the whole pageant. He insisted forever after that he had been the one virtuous soul in a den of thieves.

At least one man believed him. In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge fired Daugherty, replacing him with the upright Harlan Fiske Stone (who eventually became chief justice of the Supreme Court). Casting about for a reform-minded administrator to run the Bureau, Stone settled on the 29-year-old Hoover. For the next decade, Hoover did his best to remove the taint of the Daugherty years, advertising his new agent corps as a group of consummate professionals, insulated from political concerns or pressures. Central to their identity—and to the bureau’s legitimacy—was the idea that they would act without regard for the muck of electoral politics. They were lawyers and accountants and investigators, not politicians.

That act became harder to pull off under Franklin Roosevelt. Over the course of the 1930s, Roosevelt turned the FBI into what it is today: one part federal law enforcement agency, one part domestic intelligence service. He also showed little concern for keeping its director out of political investigations. As war approached in Europe, he pushed the FBI to investigate his domestic critics—especially those, like aviator Charles Lindbergh, who were speaking out against U.S. involvement. He also prodded Hoover back into political surveillance aimed at communist and fascist groups. Hoover went along with Roosevelt’s requests, partly because he believed in the president’s mission, partly because he hoped the FBI would benefit from its expanded role. As a young man in an appointed position during a wartime emergency, he also thought he had little choice in the matter.

Harry Truman drew Hoover further into the political scrum, though not always in ways that the White House intended. By the time Truman came to office in 1945, Hoover was a national celebrity, while Truman, who had been vice president for just three months, was still largely unknown and untested. Hoover hoped that Truman would do what Roosevelt had done: expand the FBI, this time into a global intelligence service. When Truman created the CIA instead, Hoover began to regard him as an enemy of the bureau.

Hoover’s subsequent showdowns with Truman mark the first occasions in which he took on a president and won, confident in his own ability to wield independent power. Political scientists describe this phenomenon as “bureaucratic autonomy,” the ability of career civil service officials to run their own agendas. During the Truman years, Hoover made alliances with Republicans in Congress, offering to staff their committees with trained FBI investigators in return for insulation from the Truman White House. At the same time, he worked behind the scenes to contain Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy. Though we tend to think of Hoover and McCarthy as anticommunist allies, Hoover viewed the Republican senator as a rogue actor, with a dangerous penchant for requesting that FBI files be disclosed to Congress. When asked to choose between his political loyalties and his desire to control his own bureaucracy, Hoover chose the latter.

Hoover also went after Truman, though he waited until the president was safely out of office to deliver his most serious blow. In 1953, the first year of Dwight Eisenhower’s administration, the House Committee on Un-American Activities issued a subpoena for Truman to testify in the case of Harry Dexter White, a former Treasury official accused of Soviet espionage. Hoover stepped up to testify against him.

In recent weeks, as Trump has faced his own subpoena from Congress, the Truman episode has been held up as an example of presidential defiance: Truman rejected the subpoena and refused to appear before HUAC, with no legal punishment. He did not, however, escape scot free. With Eisenhower’s backing, Hoover took the opportunity to lambast Truman before a Senate committee, accusing the ex-president of being soft on communism and of promoting White despite warnings from the FBI. One commentator called it “a political brawl of almost unprecedented rancor.” And it was Hoover, not Truman, who came out ahead. Public opinion polls after the appearance showed that just 2 percent of the American public had an unfavorable view of Hoover. Truman came away both loved and hated.

Hoover’s reputation began to decline in the 1960s, the period for which we now remember him best. Even so, he mostly got what he wanted in confrontations with the era’s presidents. John Kennedy longed to fire him but didn’t dare, citing Hoover’s popularity among Southern Democrats. Lyndon Johnson often used Hoover for his own political purposes. In an especially egregious episode, he summoned a special FBI squad to spy on civil rights activists during the 1964 Democratic National convention. But Hoover got what he wanted from Johnson, too. That same year, Johnson issued a special presidential order exempting Hoover from mandatory federal retirement at the age of 70.

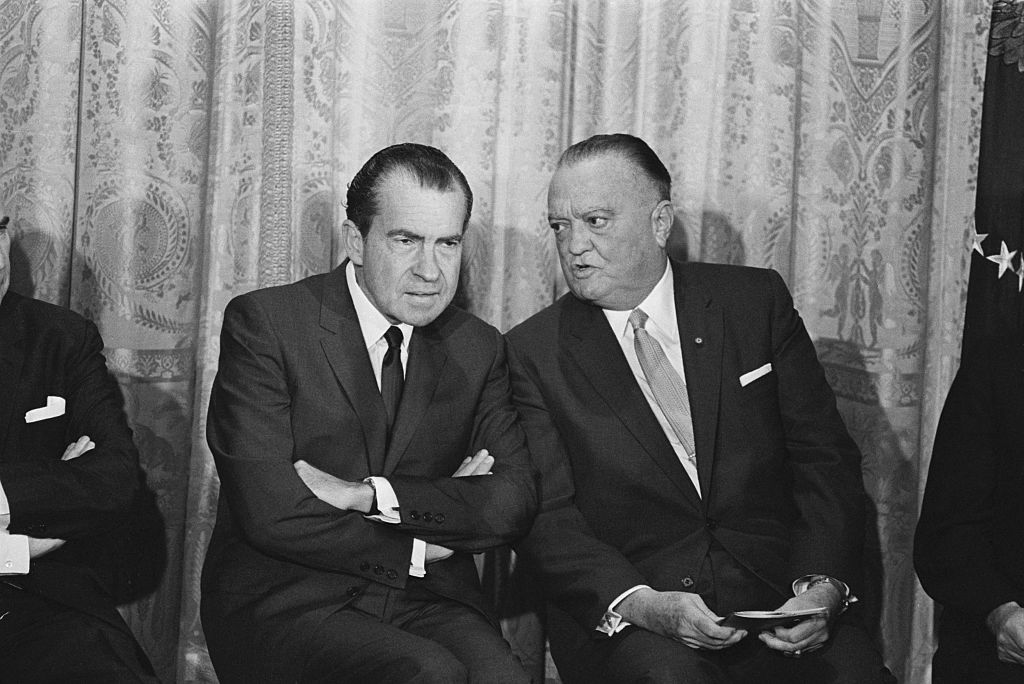

Richard Nixon initially planned to follow the Johnson model: praise Hoover and win FBI favors in return. Once in office, though, he found that the aging Hoover was still a formidable adversary. In 1970, Hoover rejected Nixon’s plan to expand surveillance of anti-war and civil-rights protesters, arguing that it was illegal and, in any case, the FBI was already doing enough. The following year, he refused to step up the FBI’s investigation into Pentagon Papers leaker Daniel Ellsberg—an act of defiance that helped to prod Nixon to establish his own dirty-tricks squad, known as the Plumbers. By late 1971, Nixon had decided he wanted to fire Hoover and went so far as to plan out a script for a breakfast meeting in which he would praise his old friend and try to talk Hoover into retiring. They had the meeting but Hoover refused to step down. Instead, he left with Nixon’s approval to expand the FBI’s overseas offices.

Appalled at Hoover’s obstinance, Nixon staffer Tom Huston complained that “at some point, Hoover has to be told who is President.” But Nixon thought “that if Hoover had decided not to cooperate, it would matter little what I had decided or approved,” as he later wrote in his memoir. It was an extraordinary admission—and one that today’s less powerful FBI directors might look upon with a touch of envy.

Hoover was arguably—and strangely—the virtuous one in those encounters with Nixon: a guardian of the law, a protector of civil liberties, a bulwark against the president’s attempts to politicize and undermine the federal bureaucracy. Hoover was acting out of self-interest but there was principle involved too. Though he abused his power countless times, in matters that have rightly earned our national outrage and censure, Hoover believed that he was acting in the country’s best interest—and in the best interests of career government servants often bullied and harangued by elected politicians.

When Hoover died abruptly in May 1972, Nixon thought that his knotty problem had been solved. Instead, Hoover’s death contributed to Nixon’s downfall. To replace Hoover as director, Nixon appointed an FBI outsider named L. Patrick Gray, and asked of Gray what Trump would later ask of Comey: “to assure [the FBI’s] complete loyalty to the Administration,” in the words of Nixon aide John Ehrlichman. He did not count on Gray’s second-in-command, a Hoover-era stalwart named W. Mark Felt, who had come up through the ranks marinated in Hoover’s ideas and methods—and who had a few ambitions of his own. Outraged at Nixon’s choice of an outsider for FBI director, Felt began leaking details of the Watergate burglary investigation to newspapers including The Washington Post, which soon dubbed him Deep Throat.

During the Trump era, the Watergate saga has once again been held up as a national morality tale. Trump supporters have framed the episode as a witch hunt, in which Deep State conspirators, colluding with craven liberals and an irresponsible press, drove an admirable president from office. Trump’s critics see just the opposite in Watergate: a shattering constitutional crisis, driven by presidential misdeeds, in which justice won out in the end.

Today’s views of the FBI tend to follow the same partisan trends. In 2022, Democrats mostly like the FBI, especially its willingness to go head to head against Trump. Among Republicans, by contrast, the Bureau’s approval rating is at an all-time low. The reasons are not hard to fathom. With Trump’s legal and political future hanging in the balance, many people regard the FBI as an instrumental force, either supporting or undermining their broader political agenda.

But the new partisan divide gets us no closer to resolving the fundamental tensions that have long shaped the FBI’s history: How much power should an FBI director have? Should the FBI be insulated from the White House or responsive to it? At what point does a bureaucracy become too autonomous—and therefore undemocratic? What should be the limits of federal and police surveillance?

During the Hoover era, the answers to those questions were determined by the actions of one singularly powerful man. Nobody thinks we should go back to that model, with its inevitable and outrageous abuses of power. But it did have one virtue: even presidents knew they could not push the FBI around. Today, we want better solutions, but we still need to think seriously about how to protect the FBI’s independence.

Adapted from Gage’s G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com