When Quentin James saw a chart tallying some of his party’s Senate spending this year, he was dismayed.

The chart listed the combined spending of the Democratic Senate campaign arm—the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC)—and the Senate Majority PAC, which is affiliated with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer. It included spending in six battleground races through the end of September. James noticed the long blue bar dominating the top of the graph, representing the money spent to support John Fetterman, the Democrats’ nominee locked in one of the most high-profile races in the country in Pennsylvania.

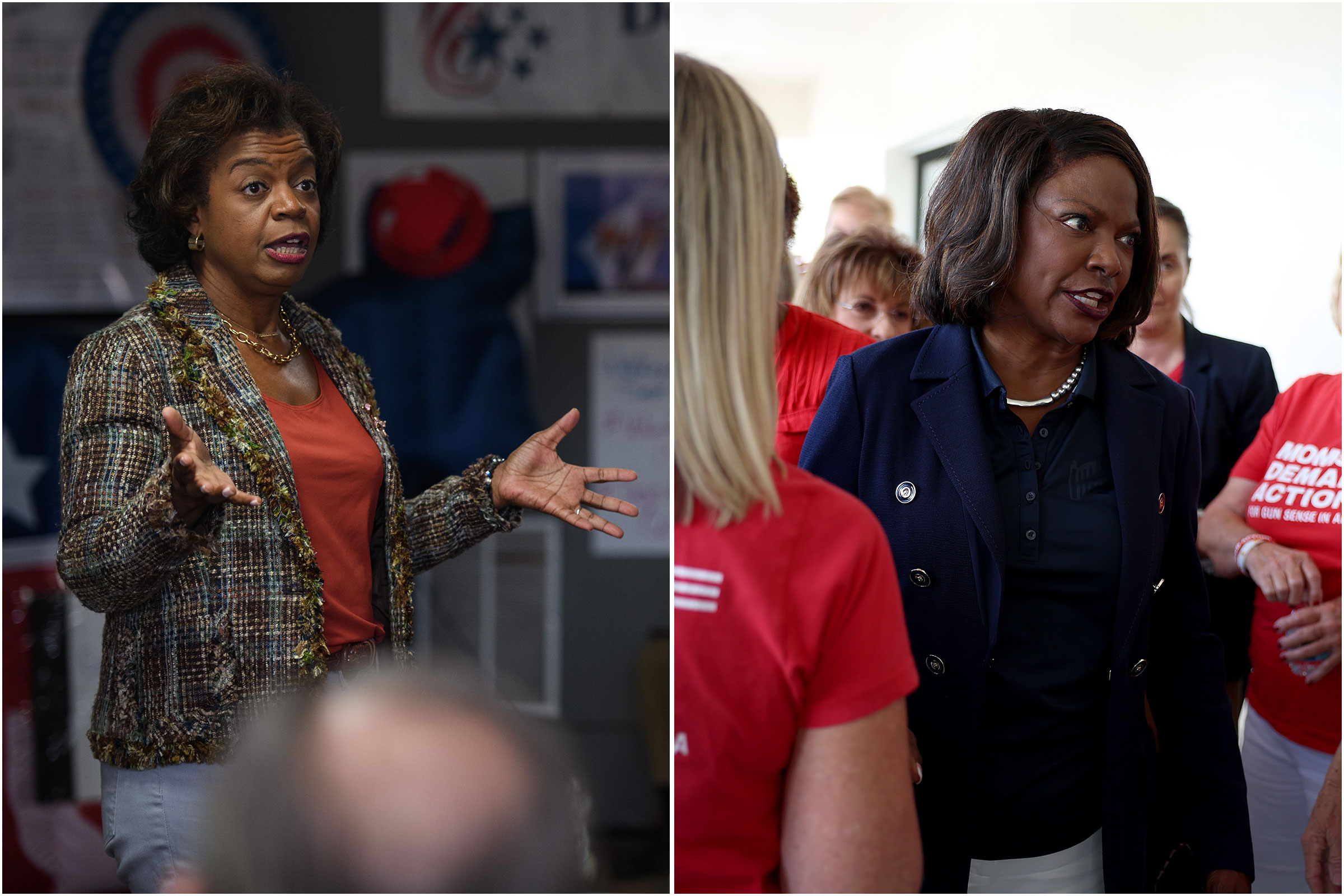

Another observation stood out: The two candidates at the bottom of the chart—Rep. Val Demings and Cheri Beasley—were both Black women.

“We understand there have to be decisions made to maximize resources,” says James, the founder and president of The Collective PAC, which works to elect Black Democratic candidates. “But it just seems as though Black candidates, Black woman candidates, always get the short end of the stick.”

Beasley and Demings are both running for Senate in states Donald Trump won twice: North Carolina and Florida. If either wins, they will be the first Black senator from their state. But as Election Day approaches, they both look like underdogs, leading some to suggest that the Democratic Party should have done more to support its Black women candidates.

The DSCC says the chart James saw provides an incomplete picture of its spending. Outside of direct contributions, the committee has fundraised for Beasley and Demings through events and emails. And James says he later learned more about spending by the Senate Majority PAC in North Carolina that wasn’t included on the graphic, making him more comfortable with its investment in Beasley’s race. Nonetheless, he and others remain frustrated about the party’s efforts on behalf of female Black candidates on the whole.

Both Beasley and Demings quickly cleared their primary fields, but faced early pessimism about the viability of their candidacies. Throughout the year, they have managed to remain within striking distance of their opponents thanks to what Democrats widely regard as sparkling biographies and strong campaigns. Beasley, previously chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, lost her bid to keep that post in 2020 by fewer than 500 votes, and previously won two statewide elections. Demings, a former Orlando police chief who was on President Biden’s V.P. shortlist, has made the Florida Senate contest surprisingly competitive.

Both campaigns have posted eye-popping fundraising numbers. According to FEC records, Demings raised more than $70 million for her Senate bid as of mid-October, while her opponent, Sen. Marco Rubio, raised slightly more than half of that. In North Carolina, Beasley raised $34 million; her opponent, Rep. Ted Budd, brought in about a third of that. Both women have proven that Black women candidates are more than just viable in swing states or those trending red; they can be among the party’s strongest.

“We know that candidates of color and especially Black women are competitive at the highest level,” said Jessica Knight Henry, the DSCC’s deputy executive director and chief diversity and inclusion officer, in a statement to TIME.“The strength of these candidates and Democrats’ commitment to their campaigns has put Republicans on defense across the Senate map, and helped position Democrats to protect and expand our Senate majority.”

But with days to go until Election Day, both races remain Republicans’ to lose. Demings has trailed Rubio in nearly every public poll, often by more than a couple points. Beasley’s race appears much closer—a poll conducted this week found her running neck-and-neck with Republican nominee Ted Budd—but she has trailed in most recent surveys as well.

Black leaders argue that the polls have been wrong before. But they also warn that if both women lose next week, the Democratic Party will face a reckoning.

“The Democratic Party has an opportunity to help them get over the hurdle,” says Rashad Robinson, a spokesman for the Color of Change PAC.

Further adding to the criticism is the case of Georgia, which Democrats managed to flip in 2020, providing Biden with the electoral votes he needed to become President and electing Democrats in two pivotal Senate runoff elections. The work of activists like Stacey Abrams, who is now making her second bid for governor, and other Black women in registering and turning out Black voters was widely seen as central to the state turning blue.

Robinson says the Democratic Party takes Black women for granted, repeatedly asking them “to vote and raise their voices, but then be excluded from opportunities to actually lead.”

“The Democratic Party has to understand that Black folks, Black women are not going to be okay simply being the foot soldiers to drive white candidates into power,” he says.

The lack of money has been what’s most discouraging for Black leaders. With some of the party’s mega-donors largely sitting out the midterms and Democratic Senate incumbents facing difficult races in Nevada and Georgia, other priorities have eclipsed the races where Black women are running.

Still, despite the scarcity, groups affiliated with the party have invested millions in North Carolina. EMILY’s list, an abortion rights group that backs female candidates, poured in almost three million dollars in September. An SMP spokesperson shared that the PAC has spent more than $22 million in total in North Carolina, including $15 million on TV, starting with a seven-figure ad in May countering a Republican attack. The investment continued with more than eight million dollars in the final month of the campaign.

There has been no comparable spending in Florida. The Miami Herald reported last month on the frustrations of some strategists who believed that a cash influx could have helped Demings close the gap there—especially in August, when Democrats’ prospects looked rosier and more outside groups were considering investing. It never materialized.

If Beasley and Demings lose, Democrats will have to grapple with why, and what might make a difference for Black women who hope to make history in future elections. The same is true in the Georgia governor’s race, although few suggest more money would make a difference there. Abrams and her leadership committee alone have brought in over $100 million. The Democratic Governors Association was her largest donor this year, contributing nearly six million dollars.

But Abrams is still trailing in the polls. Black leaders feel that she deserved more—if not money, then belief. While Abrams has often faced harsher media coverage than her fellow Georgia Democrat, Senator Raphael Warnock, much of the chatter about Georgia in Democratic circles has focused on the Senate contest. It’s a feedback loop; the polls drive interest, which drive the polls.

In the final weeks of the campaign, Abrams has drawn big name supporters including former President Barack Obama and First Lady Jill Biden. But in the eyes of some who have been watching her campaign for months, the effort feels half-hearted, especially in light of Democratic leaders for years hailing Black women as “the backbone” of the party.

“The party raises money from individuals,” says Glynda Carr, co-Founder and president of Higher Heights, which works to grow Black women’s political power. “There are thought leaders, stakeholders, and partners that helped create the echo chamber around where we’re going to make decisions. You can’t go, ‘Oh, the [Democratic National Committee] didn’t do this, the [Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee] didn’t do this.’ That is all interconnected.”

That interconnectedness makes it difficult to say who should be held accountable if all three candidates come up short this year. Abrams’ and Demings’ campaigns declined to comment for this story. Beasley’s campaign did not respond to requests for comment about whether the party had done enough to support her. She did address the question while speaking to reporters in early October, after five polls found her even with, or within one point of, Budd.

“I feel really good about the support we’re seeing nationally and here in North Carolina,” she said.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Mini Racker at mini.racker@time.com