Jameesha Harris, a councilwoman in New Bern, N.C., bought a gun and obtained a concealed-carry license to protect herself and her children against a spate of death threats from constituents. Deanna Spikula, the top election administrator in Washoe County, Nev., resigned after receiving a battery of menacing emails, including one warning her to “count the votes correctly as if your life depends on it, because it does.” After speaking out against book bans, Amanda Jones, a librarian in Livingston Parish, La., received a death threat from a man in Texas who saw a photo of her posted in a right-wing Facebook group.

Across the U.S., there has been a surge of harassment, attacks, and violent threats targeting civic and public officials and their families. America is a nation shaped by violent acts and founded on principles that protect free speech, even when it is ugly or incendiary. Yet the specter of politically motivated violence today has become alarmingly pervasive, and the fear it engenders is upending the political landscape, according to more than two-dozen interviews with analysts and public officials.

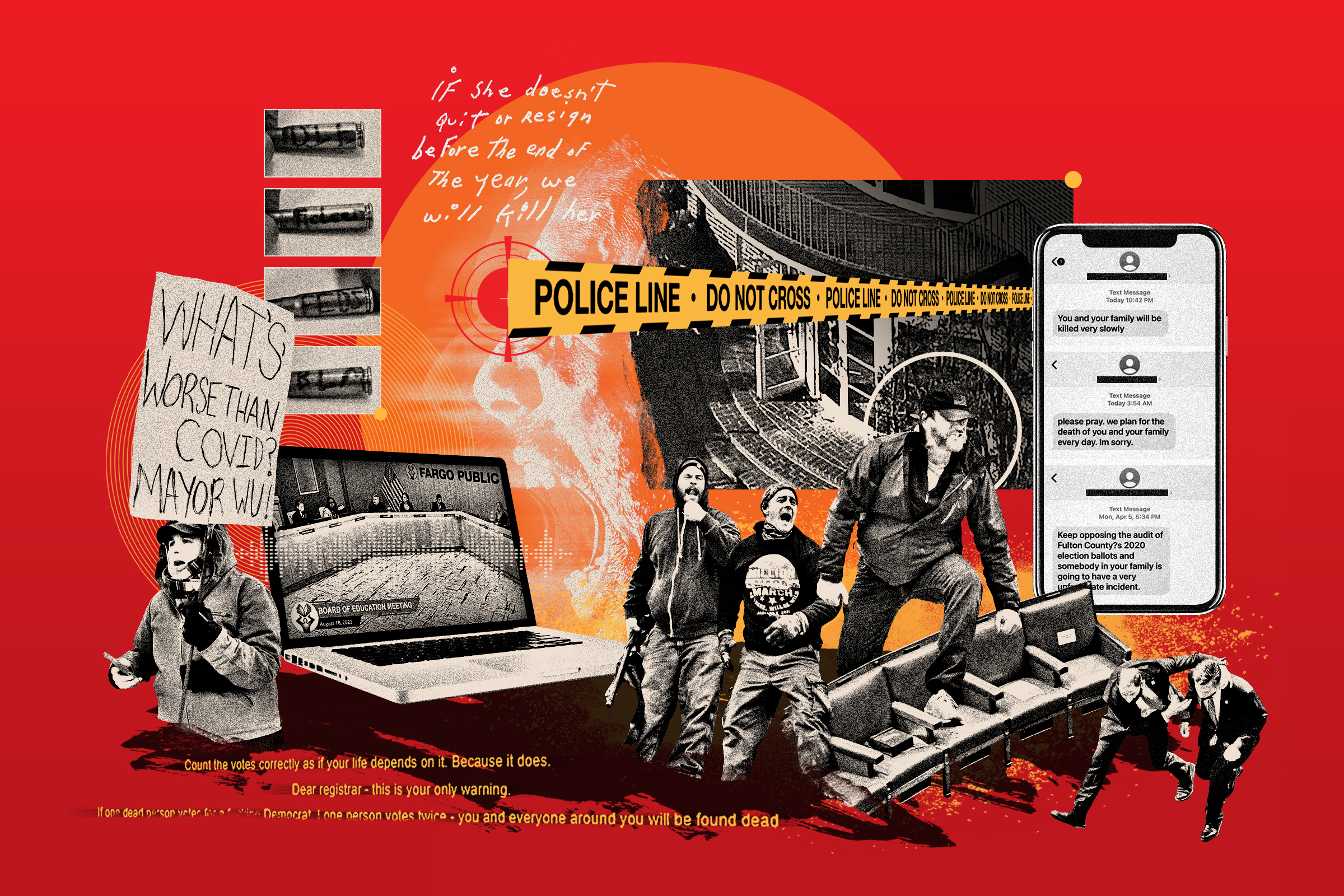

For the past year, TIME has tracked violent threats, harassment, and attacks targeting public officials and their families. News reports, public records, and interviews with experts and officials at all levels of government paint a portrait of a nation whose most basic institutions—election offices, city councils, municipal health departments, school boards, even public-library systems—are being hollowed out by relentless intimidation.

Some episodes of searing violence have made national headlines, from the insurrection in the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 to block certification of the presidential election to the Oct. 28 break-in at Nancy Pelosi’s San Francisco home, in which an intruder who allegedly threatened to break the kneecaps of the 82-year-old House Speaker hit her husband in the head with a hammer, according to prosecutors. There were more than 9,600 recorded threats against members of Congress last year, a jump of nearly tenfold from 2016, according to Capitol Police records.

But prominent politicians are far from the only targets. Threats against federal judges have spiked 400% in the past six years, to more than 4,200 in 2021. Of 583 local health departments surveyed by Johns Hopkins University researchers, 57% reported that staff had been targeted with personal threats, doxing, vandalism, and other forms of harassment during the pandemic. The U.S. Justice Department was forced to create separate task forces to combat the intimidation of public officials—one focused on threats to education workers, the other on threats to election administrators. So far, more than 100 of the latter have “met the threshold for a federal criminal investigation,” according to a statement from the agency.

“Local leadership is becoming a full-contact sport,” says Clarence Anthony, who served as the mayor of South Bay, Fla., for 24 years. Officials are dealing with angry neighbors “turning up at their front door, on their front lawns, attacking their children, attacking their family members when they go to the grocery store. They didn’t expect this as a part of the role. They didn’t sign up for this.”

Anthony is now the executive director of the National League of Cities, an advocacy network for more than 2,700 municipal governments. In a survey it published last November, 87% of local officials reported a rise in attacks, and 81% said they had personally experienced harassment, threats, or physical violence. “This is serious,” Anthony says. “It’s a real trend, and it’s disrupting America’s local government system.”

Many of these episodes of harassment fall under constitutionally protected free speech, leaving it to officials with limited resources to comb through angry threats to decipher which ones endanger their safety. They also disproportionately target officials who are women or people of color, analysts say. Several public officials told TIME the spike in violent threats has strained state and local budgets, forcing steps like hiring armed guards for their homes, installing bulletproof glass in local government offices, investing in trauma counseling for staff, and devoting time and resources to things like active-shooter trainings and monitoring emails and phone calls for menacing messages that might have to be reported to law enforcement.

Most of these threats are not made by deranged individuals or habitual criminals. They’re made by ordinary Americans acting in an environment in which the political discourse has been coarsened to the point that threats of violence have become commonplace, experts say. About one in three Americans now say they believe violence against the government can sometimes be justified, including 40% of Republicans and 23% of Democrats, according to a Washington Post-University of Maryland poll earlier this year. “Violent political sentiments used to be held by fringe groups that were disavowed by major political parties,” says Rachel Kleinfeld, who studies polarization and violence at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “Now, violent viewpoints are held by mainstream members of the right, and are growing in acceptance on the left.”

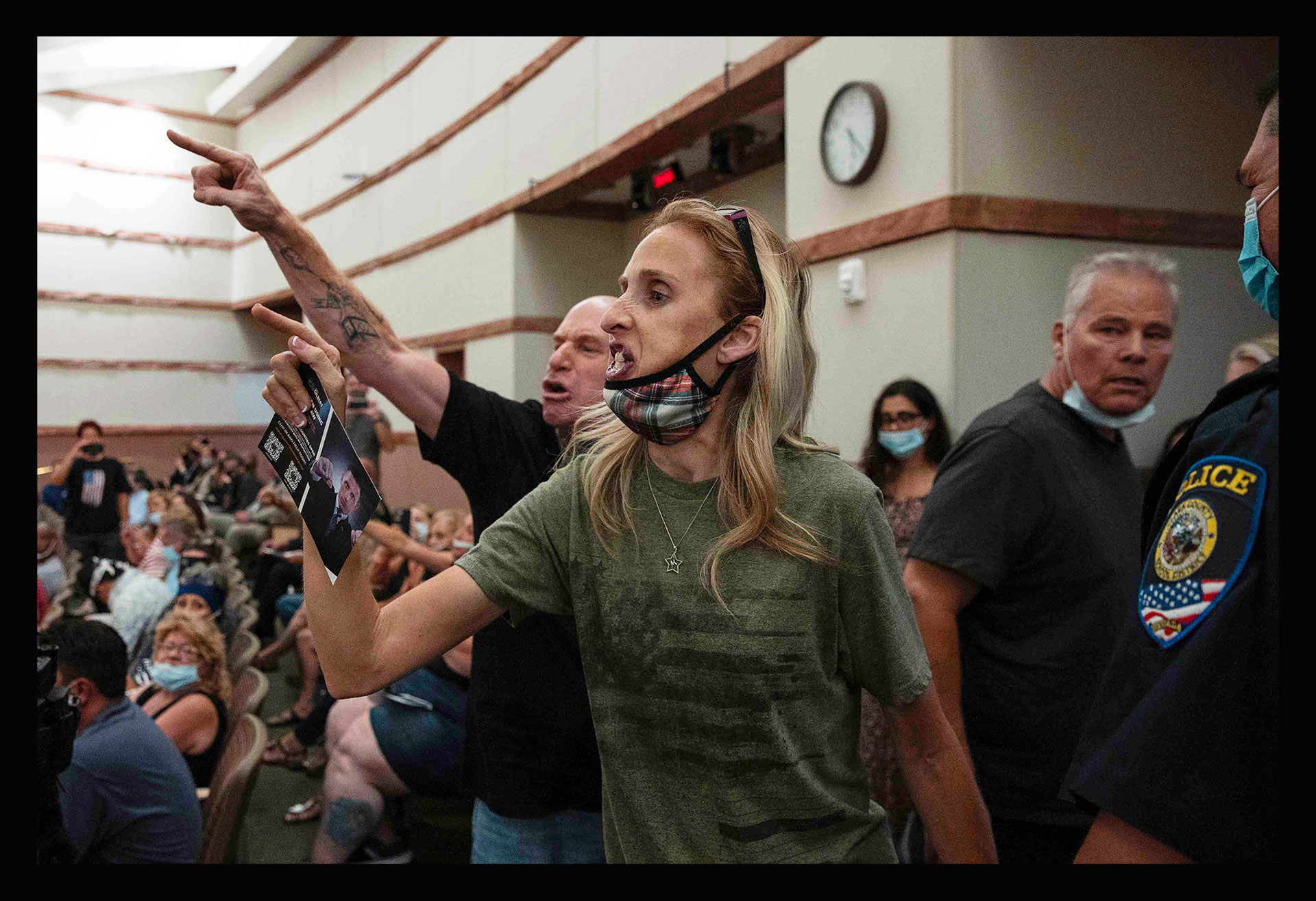

As Americans’ acceptance of violence as a political tool has jumped, previously unremarkable events and bureaucratic decisions have increasingly triggered threats and harassment, officials tell TIME. A significant number are fueled by social-media outrage that has fanned ongoing anger at America’s election infrastructure, which supporters of former President Trump falsely claim cost him the 2020 election due to widespread voter fraud. The fear and anxiety that fueled COVID-19 conspiracies has led to attacks on healthcare workers. Local school officials have increasingly come under threat for allegedly pushing “critical race theory” or inappropriate books, as well as issues related to transgender equity.

The onslaught has prompted many local and state officials to leave their positions or opt against running for re-election rather than weather ongoing abuse or risk future threats. A survey of U.S. mayors conducted last fall found that one in three had thought about leaving their jobs due to these threats, while 70% said they knew someone who had chosen not to run for office because of the same issues. “At some point, you just have to take care of yourself,” Anisa Herrera, the nonpartisan elections administrator in Gillespie County, Texas, told a local newspaper after she and her deputies resigned in August, citing persistent death threats, stalking, and harassment. “The life commitment I have given to this job is not sustainable,” she wrote in her resignation letter.

While the vast majority of Americans who make these threats won’t act on it, experts say, the prospect of becoming a target still carries significant costs. “It’s reducing the space for a community to have a discussion about fundamental freedoms,” says Shannon Hiller, the executive director of the Bridging Divides Initiative, a nonpartisan research group based at Princeton University that tracks political violence. “If people feel like they are nervous to even show up as a council member because depending on what they say their family gets threatened, it can have a real impact.” In a recent analysis of 400 threats targeting local officials, Hiller’s group found 40% were related to elections, 30% related to education, and 29% related to health and COVID-19 issues.

The demonization of government all the way down to the local level doesn’t just have a chilling effect for people inclined to public service. It’s also a sign of what experts have termed “partisan moral disengagement,” with a growing number of Americans seeing people they disagree with politically “as evil, less than human, and a serious threat to the nation,” says Lilliana Mason, a political scientist at John Hopkins who focuses on political polarization. Nor do Americans expect the situation to improve. In an August CBS News/YouGov poll, 64% of respondents said they believed that political violence will increase going forward.

To better understand how the threat of violence against public officials is transforming America, TIME collected 50 case studies—one from each state—since the attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Together, they show the scope and severity of a crisis that is eating away at the foundation of democracy.

Alabama

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Alabama’s chief health officer, Dr. Scott Harris, was issued a bulletproof vest “just in case.” He faced so many threats that law enforcement stationed themselves outside his home for protection and began escorting him to his office. Every one of his colleagues, Harris says, has had threats against themselves or their families. It has forced the department to hold tense huddles every time they need to release new public guidance in order to think through the “political implications of even normal, administrative, annual things.”

“It’s new to see this kind of vitriol. I don’t think anyone’s ever experienced anything like that in our profession,” Harris told TIME. “I’m just a doctor who came into public health. Now I had to have people with weapons sitting right outside my office—that’s just surreal.”

Alaska

Christopher Constant, an openly gay assembly member in Anchorage, was used to occasional harassment. But things took a more serious turn last year, when Constant says he was targeted for backing COVID-19 health measures and denouncing the actions of the Jan. 6 rioters, he told South Florida Gay News. He started getting openly threatening phone calls and explicit threats, which he says he forwarded to the police. At one point, he found a game camera—usually used for hunting—mounted on a tree and pointed at his house, according to information he submitted to the NLC.

Arizona

“I am a hunter—and I think you should be hunted,” said a voicemail message left in September 2021 for Arizona Secretary of State and Democratic gubernatorial candidate Katie Hobbs. “You will never be safe in Arizona again.”

“You’re a traitor to this country,” another voicemail on Aug. 2 warned. “You better put your f—–g affairs in order, cause your days are extremely numbered. America’s coming for you, and you will pay with your life.”

One caller told Hobbs she would “hang for treason.” Another just repeated: “Die you b–ch, die!” These threats, which Hobbs’s office shared with TIME, have also come to her Phoenix campaign office, which was broken into on Oct. 26, according to the city’s police, and to her home, where protesters have gathered. In July, the FBI arrested a man who had sent Hobbs a bomb threat, and whose search history included queries for “how to kill,” according to a federal indictment. (He pleaded not guilty and was released without bail.)

Arkansas

In Oct. 2021, a 43-year-old man was arrested in Paris, Ark., for allegedly threatening the lives of two county judges in Illinois who were presiding over a civil case he was involved in. “He indicated he was going to kill the judges and bury them in the ground, and told us we should take him seriously,” Chris Covelli of the Lake County, Ill., sheriff’s office told a local news site.

California

In mid-October, 45-year-old Randell Graham was arrested for allegedly threatening Conejo Valley Unified school district superintendent Mark McLaughlin. In voicemails, Graham told McLaughlin there was a “hit” on him and threatened, “We’re going to put a bullet through your skull,” according to the Ventura County Star. Graham has pleaded not guilty.

Two weeks earlier, the executive director of the California School Boards Association had sent in a letter to Gov. Gavin Newsom warning that the wave of threats targeting school officials in the state would lead to serious injury or death. ”I’ve watched in horror as school board members have been accosted, verbally abused, physically assaulted, and subjected to death threats against themselves and their family members,” Vernon Billy wrote.

Colorado

Joan Lopez, the clerk and recorder in charge of elections in Arapahoe County, Colo., is still receiving violent threats connected to the 2020 election two years later. “Some have an aggressive tone and make references to ‘treason’ or a coming civil war,” she says. “Even scarier, a few have been very specific and mention individuals such as me, by name.” Lopez recently received a handwritten letter, which TIME viewed, in which the writer called her a “c-nt” and claimed to know where Lopez lived.

As the midterm elections draw near, staff in her office are on edge. “On one hand, it is frustrating because we work very hard to be transparent and educate the public about how the system works,” Lopez says. “On the other hand, it is frightening. Most of these messages turn out to be nothing, but as the saying goes, you never know.”

Connecticut

A 42-year-old man was arrested and charged with second-degree threatening and second-degree harassment in September for sending threats to state Rep. Tammy Nuccio, a Republican, after a campaign sign was mistakenly delivered to his home. Nuccio told local media that despite the man’s initial apology, she left town when aides discovered an additional threatening voice message and said she was worried about him attending her upcoming public appearances. “The threat directed toward me from a constituent was extremely frightening to both my family and myself,” Nuccio said. “Our home lives have been irreparably impacted.”

Delaware

In Feb. 2021, 19-year-old Samuel Gulick pleaded guilty to fire-bombing a Planned Parenthood facility in Newark, Del., attacking it with a Molotov cocktail and spray-painting the phrase “Deus Vult”—Latin for “God’s Will”—in red paint. Gulick had posted right-wing memes and threats against abortion providers on his social media, according to the FBI, comparing those who support access to abortion to Nazis.

“Attacking and terrorizing law-abiding citizens to achieve personal political goals is a heinous act,” L.C. Cheeks, Jr., one of the special agents in charge of the investigation, said in a Justice Department statement when Gulick was sentenced to 26 months in prison in March 2022.

A year after the attack, the Planned Parenthood facility was still getting threats, CEO Ruth Lytle-Barnaby said in a radio interview. According to a report by the National Abortion Federation, assaults directed at abortion clinics and their staff increased 128% last year.

Florida

After becoming a member of the Brevard County School Board, Jennifer Jenkins, a Democrat, supported the district’s move to impose mask mandates in defiance of Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis’s executive order banning them. In response, Jenkins says her car was followed, her phone number was posted online to encourage harassment, and protestors gathered outside her house, where someone burned “FU” into her lawn with weed killer. “We’re coming for you,” the protesters yelled, according to Jenkins. “We are going to make you beg for mercy. If you thought Jan. 6 was bad, wait until you see what we have for you!”

Unlike many other local officials, Jenkins went public with the threats she and her family have endured. “Unfortunately it takes one person to terrorize you,” she said in a television interview. “And when there’s no consequences for it, it becomes the norm and it becomes acceptable.”

Georgia

After Georgia’s Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger refuted Trump’s false claims of widespread voter fraud in the state’s 2020 presidential election, his family had to leave their home and go into hiding. The property had been burglarized and people who identified themselves to police as members of the far-right Oath Keepers militia were found outside their home, the Raffenspergers told Reuters.

Well into 2021, the family of Georgia’s top election official was still getting targeted threats. Tricia Raffensperger received a series of text messages in April of that year warning that a family member was “going to have a very unfortunate incident,” that they planned “for the death of you and your family every day,” and that “you and your family will be killed very slowly,” according to Reuters.

Hawaii

Escalating levels of harassment led Hawaii lawmakers to introduce a bill earlier this year seeking criminal penalties for threatening school officials. In a letter supporting the legislation, Keith Hayashi, the state’s interim superintendent of education, cited the “growing problem of continuous and threatening harassment of educational workers by parents and members of the public.”

“The polarization of society and overt disrespect for our government institutions that are fostered by social media have emboldened certain persons to harass and intimidate school officials with demeaning swear words and threats to their personal safety,” he wrote.

Idaho

In April 2021, 33-year-old Erik Ehrlin was arrested with four firearms, tactical gear, zip ties, duct tape, rubber gloves, a balaclava face mask, high-capacity magazines, a bag of ammunition, and bullets painted with the words “Die McLean.” Lauren McLean is Boise’s mayor.

U.S. Attorney Josh Hurwit said Ehrlin “poses a serious risk of violence to those with political viewpoints that differ from his own radicalized beliefs.” Ehrlin vandalized signs with messages like “Warning(:) Federal Employees Shot on Site,” according to court documents, as well as references to “SAI,” referring to the right-wing extremist group Sovereign Alliance of Idaho. “A search of Ehrlin’s cell phone revealed text messages where he described ways to commit mass violence against those with differing political views than him,” prosecutors said. Ehrlin pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 78 months in prison for unlawful possession of a firearm and assaulting a federal officer when he was arrested.

McLean released a statement about the toll threats and harassment have taken on her and her family. She said she was speaking out because “this trend of violent intimidation has resulted in a wave of officials stepping away from public service,” which she worries is endangering democracy.

“I’m incredibly disheartened to see good people stepping down from public service because of the impacts that threats—very real threats—have on their sense of security, on their families, on their ability to serve their communities and fulfill their duties,” she said. “I understand the decision to leave public office because I still feel intensely the fear, frustration, and helplessness of watching my two children quietly take in news of thwarted threats against me and learning that they, too, were being targeted and tracked online.”

Illinois

In February, State Rep. Deb Conroy shut down her county office after getting multiple death threats. They came after Conroy, a Democrat, proposed legislation that would require state data to be released more quickly to local health departments. The measure was seized on by right-wing groups, who falsely claimed Conroy supported “concentration camps for unvaccinated people,” according to a local news station.

“At least four of our Democratic colleagues have received threats against their lives, their loved ones or their place of worship in recent months,” House Speaker Chris Welch wrote in a Feb. 7 letter to House Republican Leader Jim Durkin. “The situation was made worse when a member of your Republican caucus issued a statement fanning the flames of this vitriol with the same inaccurate information…We’ve all watched this intolerant partisanship worsen each year poisoning our politics, and it is now seeping into the crevasses of our daily lives.”

Indiana

A 26-year-old man from Morocco, Indiana was arrested in May for threatening the state’s Supreme Court justices. “I am serious,” David Wayne Goetz II allegedly wrote in an email. Another message threatened “a bloodbath” and asserted that Goetz had the right to kill every single cop and judge in the country. He was charged with two counts of intimidation.

Iowa

Mark Rissi, a 64-year-old resident of Hiawatha, Iowa, was indicted on Oct. 6 for allegedly leaving death threats in voicemails to Maricopa County, Ariz., election officials and the Office of the Arizona Attorney General. In the messages, Rissi allegedly threatened to hang officials for the “theft of the 2020 election,” according to the Justice Department. “You’re gonna die, you piece of sh-t,” he said, according to the indictment. “We’re going to hang you.” He has pleaded not guilty and has been released without bail.

Kansas

A 31-year-old Kansas man is facing a felony charge for threatening to kill GOP Rep. Jake LaTurner in a June 5 voicemail. Chase Neill was arrested 19 days later after he allegedly continued to make threatening calls. According to prosecutors, Neill indicated he believed he was “obligated by God” to warn “certain public figures,” and had threatened other members of Congress. A trial has been put on hold while the court evaluates his mental state.

Kentucky

On Valentine’s Day this year, 21-year-old Quintez Brown allegedly walked into the Louisville campaign office of Democratic mayoral candidate Craig Greenberg and started firing a 9-mm handgun in what police described as an attempted assassination.

“When we greeted him, he pulled out a gun, aimed directly at me, and began shooting,” Greenberg, a Democrat, told a press conference. One bullet went through Greenberg’s sweater but did not injure him, according to law enforcement.

Brown faces federal charges of “interfering with a federally protected right, and using and discharging a firearm in relation to a crime of violence by shooting at and attempting to kill a candidate for elective office.” Brown had also allegedly conducted internet searches on Republican candidate and Jeffersontown, Ky., Mayor Bill Dieruf, according to prosecutors. The month before the attack, he wrote what he called “A Revolutionary Love Letter,” in which he described America as a nation in a state of “political warfare” and argued “voting and petitioning will not be sufficient for our liberation.” The government argues that the article shows Brown was radicalized to political violence. Through his lawyer, Brown has pleaded not guilty to the charges, which could carry a life sentence.

Louisiana

Amanda Jones, the head of the board of the Louisiana Association for School Librarians, found a death threat in her inbox in July. A month earlier, the middle school librarian had spoken out against censorship and book bans at her local public library in Livingston Parish, especially books about people of color and LGBTQ people. The man who Jones says threatened her was four hours away, in Texas, and had found her after a right-wing Facebook group called “Citizens For a New Louisiana” had posted a photo of her. “It was pretty explicit in the ways that he was going to kill me,” Jones told Education Week. “I was actually petrified.”

Maine

“If you vote for that [expletive] Black [expletive] I’ll kill you,” a man said in a voicemail left for Republican Sen. Susan Collins’s office in May, in an apparent threat over Collins’ vote to confirm Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court.

Earlier this year, someone smashed a window in Collins’s home in Bangor, in a location that suggested to the senator that it had been “studied and chosen,” she told the New York Times in October. “I wouldn’t be surprised if a Senator or House member were killed,” Collins said. “What started with abusive phone calls is now translating into active threats of violence and real violence.”

Maryland

In June 2021, Kristin Mink, a candidate for the Montgomery County council, received violent threats through her campaign website. The person said that they hoped someone would attack Mink with a baseball bat and kill her child. “This should not be normalized,” she wrote on Twitter. “This. Is. Not. Normal. I’ll say it until it’s true.”

Massachusetts

Rachael Rollins, the first Black woman to serve as U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts, has been targeted by a barrage of violent and racist threats. During her confirmation vote in Dec. 2021, the Biden nominee was slammed by Republicans for her decision not to prosecute some low-level crimes as a district attorney. As a result, her office was flooded with vitriol.

“SOMEONE, SOMEWHERE IS PLOTTING TO PUT ONE IN YOUR FACE OR HEAD!!!” read one email turned over to the U.S. Marshals Service for investigation. “You’ll probably die,” read another. While Rollins requested a full security detail, federal officials declined, rejecting the argument that she was in serious danger, according to the Boston Globe.

Michigan

A Wolverine State health official says he was almost run off the road twice in Aug. 2021 by a woman driving more than 70 miles per hour, in an incident that punctuated a torrent of abuse by critics of the state’s COVID-19 restrictions. The incident occurred hours after Adam London, the director of Michigan’s Kent County Health Department, issued a controversial mask mandate for some schools.

“I need help,” he wrote in an email to county commissioners obtained by Michigan Advance. “My team and I are broken. I’m about done.”

Minnesota

Bob Nystrom, the board chair of Brainerd Public Schools in Minnesota, had to start asking the district superintendent to make sure police were stationed nearby during school board meetings after ongoing harassment and threats during the summer and fall of 2021. Amid debates over requiring masks in schools and how to teach about race, threats were directed at him, along with anonymous threats against the entire board, with critics saying they would “break into members’ homes or beat them,” according to a report on education news site The 74 Million.

“In a small town like this, that’s just never happened,” Nystrom told the outlet. “This is scary, that you have to have a police officer in the meeting to protect you.” By Jan. 2022, three board members in Brainerd had quit. Across the entire state, nearly 70 school board members resigned their positions in 2021, three times as many as in a regular year, according to the Minnesota School Boards Association.

Mississippi

In the summer of 2021, Mississippi’s top health official, Dr. Thomas Dobbs, received threatening phone calls after he urged residents of the state to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Many of them mentioned a conspiracy circulating on social media that falsely claimed that Dobbs’s son, who is also a doctor, was getting kickbacks from the World Bank for his father’s public support for vaccination. “I get zero $ from promoting vaccination,” Dr. Thomas Dobbs tweeted. “ALL LIES.”

Missouri

After 14 years leading Franklin County’s health department, Angie Hittson resigned in Dec. 2021. “The daily verbal assaults, threats of violence and even death threats directed at the department, my family and at me personally for following orders I was directed to follow, are not only unbearable, they are unacceptable,” Hittson wrote in her resignation letter, which was posted on a local news site.

Hittson had hoped to serve in the role until her retirement. “Resigning was not an easy decision for me,” she wrote. “It was one I felt I had to make for my own safety and well-being.”

Montana

A 44-year-old man in Bozeman, Mont., was charged with five counts of threats and improper influence in official and political matters in July after allegedly posting menacing messages on social media directed at the city council.

“I wish extreme violence against every #Bozeman elected official. They *all* deserve to dangle from a tree,” Robert Brigham tweeted, according to prosecutors’ charging documents, which said that the defendant had confirmed the messages were his.

Nebraska

In one of the first cases brought by the Justice Department’s task force investigating threats against election officials, 42-year-old Travis Ford of Lincoln, Neb., was sentenced Oct. 6 to 18 months in prison for making online threats towards Colorado’s top elections official.

“Do you feel safe? You shouldn’t. Do you think Soros will/can protect you?” he wrote to Secretary of State Jena Griswold, according to the FBI. “Your security detail is far too thin and incompetent to protect you.”

Expert say this diffusion of violent threats across state lines, often targeting officials across the country, is a new phenomenon that is making it more difficult for law enforcement.

Nevada

“If one dead person votes for a fu–ing Democrat,” one of the menacing emails to Washoe County’s Deanna Spikula read, “you and everyone around you will be found dead.”

Spikula, 48, who worked as registrar of voters, was the target of a barrage of threats after a pro-Trump conspiracy theorist began harassing her at county commissioners’ meetings in February, accusing her of “treason” and demanding to “either fire her or lock her up,” according to Reuters.

Soon after, Spikula resigned. “You start to get that fight-or-flight feeling when you’re on the receiving end of that stuff,” she told the Reno Gazette-Journal in July. “When I’d get a notification that my doorbell detected a visitor, I’d be sitting there on the phone trying to see what I can see and checking on my kids and everything else.”

New Hampshire

In Sept. 2021, New Hampshire’s Executive Council in Concord had to cancel a meeting in which they intended to debate whether to accept $27 million in federal vaccine aid, citing concerns for the safety of the state employees. The council members were escorted out to their cars by police past an angry crowd. “A few individuals there…were getting very aggressive [with] very open threats, and that’s just not going to be tolerated,” Republican Gov. Chris Sununu said. The following month, nine people were arrested while disrupting another meeting, according to reports.

New Jersey

Last November, a 46-year-old man in Newark, N.J., was charged with threatening to assault and murder a United States judge. “Before the snow starts falling on my head, I’m gonna put a bullet in the Judge’s brain,” Jonathan Williams said, according to prosecutors. He called again, telling an employee in the judge’s chamber: “You’ll see! You’ll lose your job when I kill your boss.” The next day, security guards stopped him from entering the law offices when he said he was “going to blow the judge’s brains out.”

New Mexico

After the 2020 election, Maggie Toulouse Oliver, New Mexico’s Secretary of State and top election official, had her photo and home address posted on a website called “Enemies of the People.” She received so many threats she had to leave her home for weeks, remaining under state police protection.

“In New Mexico, the conspiracies about our voting and election systems have gripped a certain portion of the electorate and have caused people to take action,” she testified before the House Homeland Security Committee in July. “But more recently, especially since our June 2022 primary election, my office has experienced pointed threats serious enough to be referred to law enforcement.”

New York

In April, the New York Police Department had to provide security for the city’s health commissioner, Ashwin Vasan, after more than two dozen people gathered outside his home to protest the decision to keep school mask mandates in place for children under 5. The group was “banging on the doors of my health commissioner even though his children are inside, yelling and screaming, threatening his life,” Mayor Eric Adams said at a press conference.

“I never thought I would experience the nature and scale of vitriol I have faced online and in-person,” Vasan, an epidemiologist, said on Twitter.

North Carolina

Many of the local officials who spoke to TIME would not go public with accounts of their threats, saying they did not want to draw any more attention to themselves or their families. Several said they had spent money on additional security for their homes, and had considered moving but realized their addresses would remain public. “I acquired a concealed carry license and handgun after members of my community threatened my life and posted my address online,” Jameesha Harris, a councilwoman in New Bern, N.C., told the NLC last year, before losing re-election. “I have to protect myself, my family and my kids.”

North Dakota

School board members in Fargo were inundated by threats in August after their decision to stop saying the Pledge of Allegiance at meetings drew right-wing outrage. Nyamal Dei, the only Black board member, played one of the many threatening voicemails she had been sent at an Aug. 18 board meeting.

Much of the harassment came from afar: Only 19% of the messages board member Greg Clark received were from Fargo residents, he said. Of those that did come from Fargo, nearly half supported the board’s decision, Clark added. Yet board members said they felt compelled to reverse its decision in an effort to stop the threats.

“I’d like to apologize to those good people of Fargo for what I am about to do,” Clark said at the August meeting. “In a few minutes I’m going to vote to reinstate the Pledge of Allegiance here, having been directly influenced by people I was not elected to represent. But I hope you’ll forgive me…The disruptions and the threats must end so that we can have a successful start to our school year.” In the end, Dei was the only one who voted against the reinstatement of the Pledge.

Ohio

On Aug. 11, a man wearing body armor and carrying an AR-15 rifle allegedly tried to break into an FBI office in Cincinnati. He fired a nail gun at law enforcement before fleeing the scene. After a six-hour standoff with police, he was eventually shot and killed, according to authorities.

Ricky Walter Shiffer, 42, had previously posted on Truth Social about his desire to “kill” FBI agents after the agency’s search of Trump’s residence at Mar-a-Lago to retrieve sensitive documents, according to court filings. “The divide between violent rhetoric online and real-world violence is closing,” Brian Murphy, a former head of the DHS intelligence branch, told TIME after the incident.

Oklahoma

Angry over public-safety guidelines for masks and vaccinations, James Scott Moore, 53, allegedly threatened to blow up the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration office in Oklahoma City on Jan. 13. Local police received a tip that Moore was planning to rent a truck, fill it with gasoline, blow up the building, and then take his own life, according to investigators. Police say that when he was arrested at his home shortly after issuing the threat, he was armed with two handguns. He has pleaded not guilty.

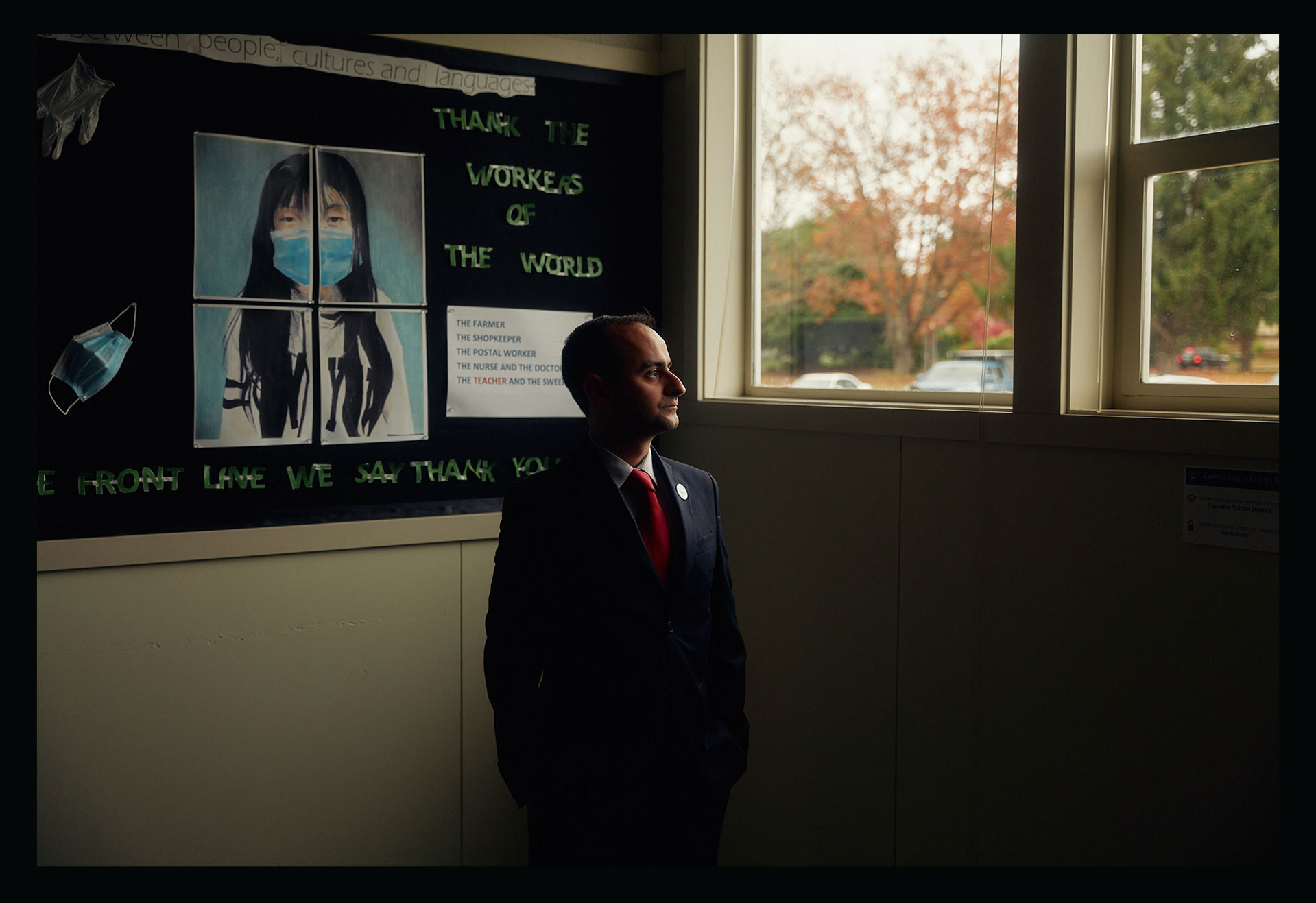

Oregon

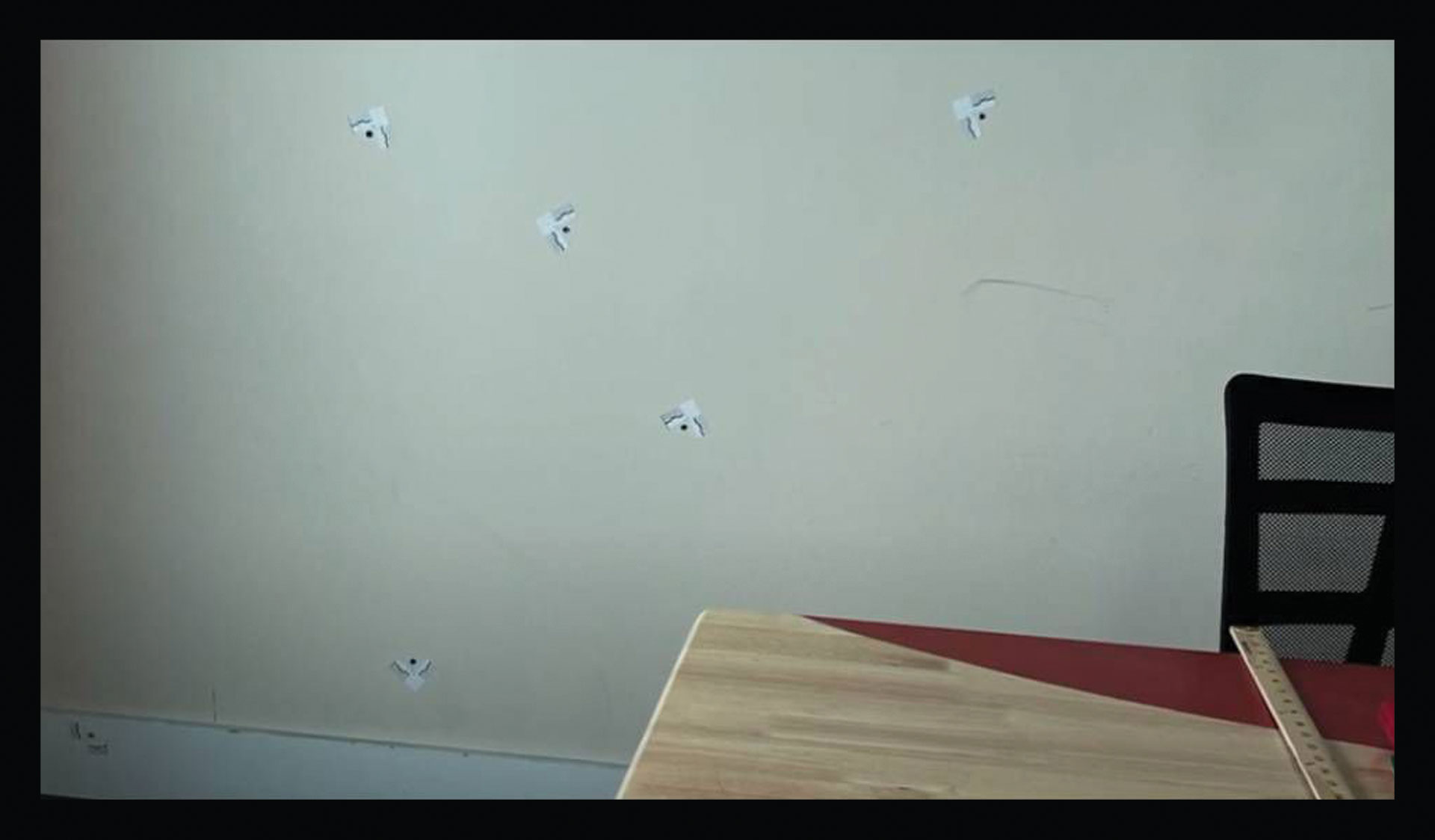

The only thing Sami Al-Abdrabbuh knows about the man who was looking for him is the type of shoes he was wearing. In May 2021, shortly after Al-Abdrabbuh was re-elected to the school board in Corvallis, Ore., a friend texted him that a man had shown up with a campaign flyer asking neighbors where Al-Abdrabbuh lived. “He was talking to them from behind the fence, telling them that he would kill me, and that he would kill them if they would not show him where I was,” Al-Abdrabbuh tells TIME.

Around the same time, he got a text with a photo of one of his lawn signs at a shooting range. The sign had target markets on it and was riddled with bullet holes, he says. “This shouldn’t be what happens in a civilized democracy,” says Al-Abdrabbuh, who believes he was targeted for his defense of pandemic health restrictions and his support for teaching America’s history of racism.

Al-Abdrabbuh says he worries that speaking about the threats he’s experienced will discourage other people from undertaking public service. “Think of it as a building, and we’re chipping away at its pillars,” he says. “If we end up in a situation where we don’t have enough qualified people who want to continue to serve, it’s going to be really dangerous for our democracy and for our community.”

Pennsylvania

In August, a 46-year-old Pennsylvania man was arrested for threatening to murder FBI agents after the search of Mar-a-Lago. “Every single piece of s–t who works for the FBI in any capacity, from the director down to the janitor who cleans their fucking toilets deserves to die. You’ve declared war on us and now it’s open season on YOU,” Adam Bies, 46, wrote on the right-wing app Gab, according to the indictment. “We the people cannot WAIT to water the trees of liberty with your blood,” he wrote in another post. “My only goal is to kill more of them before I drop.”

Bies was echoing violent rhetoric amplified by right-wing commentators and even some lawmakers, who were using terms like “civil war.”

“Republican politicians and media figures are playing with fire,” Kleinfeld, the political violence analyst at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told TIME in August. “Acceptance of violence for political ends in America is approaching the levels seen in Northern Ireland at the height of their Troubles…fanning the flames of violence through incendiary language is the worst possible thing they could be doing.”

Rhode Island

Tiara Mack, the only Black, LGBTQ woman in the Rhode Island Senate, was first inundated with threats in January. She had just sponsored a sex-education bill that drew conservative backlash from parents concerned about “indoctrination.” Letters poured in from around the country, she says.

Then, over the July 4 holiday, the 28-year-old posted what was supposed to be a light-hearted campaign video on TikTok, which showed her twerking upside down on a beach. The video went viral on right-wing media, with commentators like Fox’s Tucker Carlson blasting it. Mack was spammed with hundreds of racist, homophobic, and often violent threats, more of 200 of which she shared with TIME. “Where are you located? I wanna have a little chat face to face with the corruptor of kids,” one of the messages said. “Cause I think women deserve equal rights…and lefts. Take that however you’d like. It’s not a threat, it’s a promise.”

“It was just overwhelming,” says Mack, who says she had to explain to the FBI why threats calling her “groomer” were shorthand for saying she preyed on children. “I still don’t think I’ve been able to fully articulate to white people how dangerous and scary it is to be a queer young person of color in elected office.”

South Carolina

In July, state Rep. Wendell Gilliard received more than a dozen violent threats, including death threats, when the Democrat announced that he intended to file a bill to ban assault-style weapons.

“First, you get the phone calls. The N-word this, the N-word that,” Gilliard told the Charleston City Paper. “Then when you get on Facebook, [they say] if he’s not going to uphold the Constitution, then we ought to do something.” Later he added, “They said things like, ‘If he can’t do his job, we need to take care of him.”

South Dakota

After the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, both Democratic and Republican lawmakers faced a surge in violent threats ahead of Joe Biden’s inauguration. GOP Rep. Dusty Johnson, South Dakota’s sole member of the U.S. House, said he received death threats, including one saying he should be “hung up in the street.”

Johnson said the police department in Mitchell, S.D., was forced to monitor his family’s security. “U.S. Air Marshalls, which do not normally provide security to members of Congress, have been making sure that I’m safe in the airports and on the planes,” he said.

Tennessee

In September, the FBI received a tip that a man was posting TikTok videos about carrying out a violent attack, threatening to “go to war against the government.” The user said he was ready to “grab my rifle and go to DC and take this country back physically.”

“When we do, we will eradicate every m—— that is part of a communist mindset,” Bryan Perry of Clarksville, Tenn., allegedly said. “No mercy. No surrender.” According to authorities, the 37-year-old then linked up with Jonathan O’Dell of Warsaw, Missouri, and made plans to go “hunt” undocumented immigrants on the southern border.

When FBI agents showed up at O’Dell’s house on Oct. 7, a day before they planned to leave, the two men fired at least eight rounds at the agents’ vehicle before being arrested. Both Perry and O’Dell have pleaded not guilty.

Texas

Three months before the 2022 midterm elections, all three people running the election office in Gillespie County, Texas resigned their positions, citing persistent death threats and harassment. “The life commitment I have given to this job is not sustainable,” Anissa Herrera wrote in an Aug. 2 letter to the Gillespie County Elections Commission, citing “threats against election officials and my election staff.” She told local media she had been threatened and stalked.

Sam Taylor, a spokesman for the Texas secretary of state’s office, said in a statement to TIME that threats on election officials “are reprehensible” and should be reported to law enforcement immediately. “Unfortunately, threats like these drive away the very officials our state needs now more than ever to help instill confidence in our election system.”

Utah

Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold got a message in Aug. 2021, warning her that she was being watched as she slept. “You broke the law. STOP USING YOUR TACTICS. STOP NOW. Watch your back. I KNOW WHERE YOU SLEEP, I SEE YOU SLEEPING. BE AFRAID, BE VERRY AFFRAID. I hope you die.”

Eric Pickett, a 42-year-old who worked at a youth treatment center in Utah, allegedly sent Griswold the message after watching online talks in which people pushed election conspiracy theories, according to a report by Reuters. Pickett told the outlet he “didn’t know they would take it as a threat” and thought they would consider it as “somebody just trolling them.”

The officials on the receiving end of such angry messages, however, say they have to take them seriously. “It’s falling on Secretary of States offices to comb through literally thousands of threats,” Griswold later told a local news station in Denver. Long after the resolution of the race, she added, “the lies about the 2020 election are actually growing stronger.”

Vermont

Vermont Secretary of State Jim Condos rattles off the litany of recent violent threats received by his office. “That our time was up, that we’d be hanged or executed by firing squad, that our days were numbered, that we would—excuse me—get ‘effing popped,” he says. “Do it the easy way. Put the gun in your mouth and hold the trigger.” Last summer, a member of Condos’ staff took a leave of three months to receive counseling for PTSD, the Secretary of State told TIME.

Over the past year, Condos has pressured state lawmakers to support measures that would make it easier to charge people for criminal threats and impose steeper penalties when they threaten public officials. “They appear to know just how far they can go without crossing the line,” Condos says. “This misinformation is so insidious that it drives people to make these threats against sworn election officers who are really just doing their jobs.”

Virginia

In April 2021, vice chair of the Loudoun County school board Atoosa Reaser decided to publicly share one of the disturbing threats she had received. “Don’t be surprised when you low-IQ, poorly educated, and morally bankrupt pinko traitors are dragged from your beds in the middle of the night and hanged by the neck until dead by the righteously angry parents of your community,” the message read.

Reaser says such threats, which came in a torrent amid heated debates over COVID-19 measures and transgender and racial-justice issues, were debilitating for board members. “It has an effect on you that you can’t really put into words, when someone describes the way they want to come into your home and end your life, and you start thinking about the people who live with you,” she told a school board meeting that June.

Washington

A 48-year-old man was arrested in July after allegedly yelling racist threats outside the Seattle home of Democratic Rep. Pramila Jayapal. The man, later identified as 49-year-old Brett Forsell, was wearing a Glock pistol in a holster on his waist when the police arrived to arrest him, authorities said.

“In a time of increased political violence, security concerns against any elected official should be taken seriously, as we are doing here,” Casey McNerthney, a spokesman for the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office, told the AP. Forsell has pleaded not guilty.

West Virginia

In August, a West Virginia man who sent a series of emails over seven months threatening to kill Dr. Anthony Fauci and other federal health officials was sentenced to 37 months in prison. According to his plea agreement, Thomas Patrick Connally, Jr., 56, used an encrypted email service to send repeated threats, including one that said Fauci and his family would be “dragged into the street, beaten to death, and set on fire.”

Wisconsin

Retired Wisconsin judge John Roemer was zip-tied to a chair before being shot and killed in his New Lisbon home on June 3. Roemer was one of several people the attacker, Douglas Uhde, intended to target. Uhde, 56, had spoken of “taking care of” a Michigan judge as well, according to authorities, who said they found an apparent hit list in his vehicle, which included Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell and Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat. Police found Uhde with a self-inflicted gunshot wound at the scene of Roemer’s shooting. He died four days later. Wisconsin Attorney General Josh Kaul called the murder a “targeted act” against the judicial system.

Wyoming

In March 2021, a federal grand jury charged a Wyoming man with making death threats to various elected officials, including GOP Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida. “I will [expletive] see that Matt Gaetz gets killed when he gets here,” Christopher Podlesnik, 51, said in a voicemail, according to prosecutors. “You let Gaetz step into the State of Wyoming, not only is he going to be dead…you’re going to be dead,” he said in a message left for Wyoming Republican Sen. John Barrasso.

Podlesnik pleaded guilty to four counts of transmitting threats in interstate commerce and was sentenced to 18 months in prison and fined $10,000.

With reporting by Leslie Dickstein and Julia Zorthian

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Vera Bergengruen at vera.bergengruen@time.com