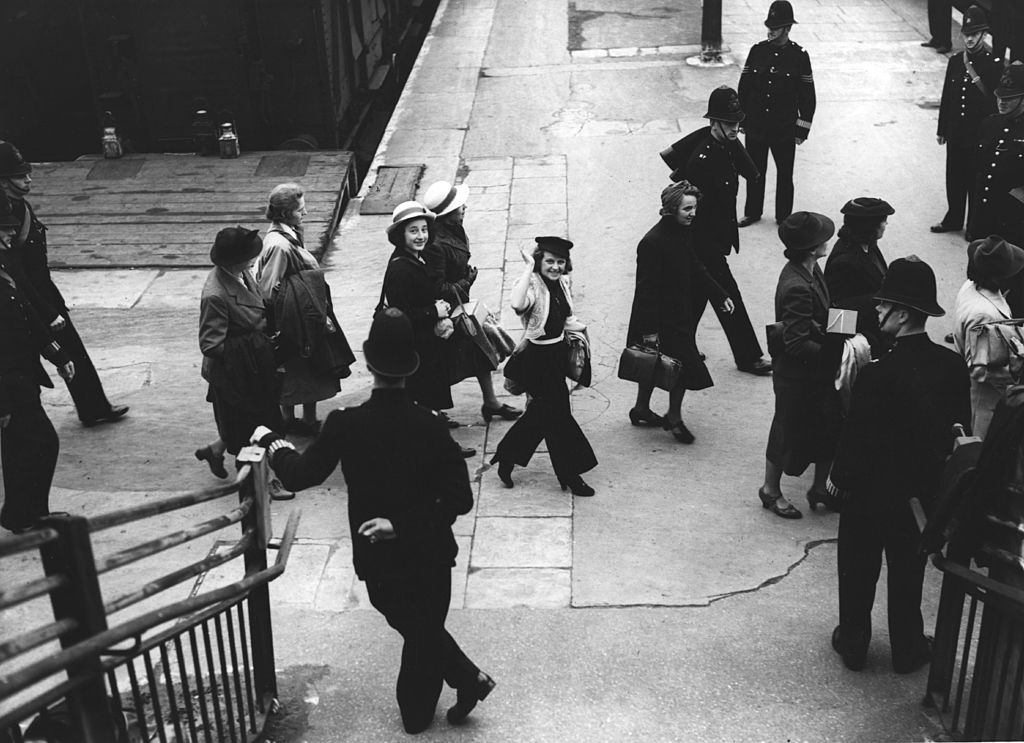

On the morning of Sunday 12th May 1940, a fleet of motor cars roared from Scotland Yard, London’s police headquarters. Many of the officers dispatched to make the day’s arrests had been unaware of their task until they arrived at work that morning. By the end of the day, around two thousand individuals had been taken into custody to be handed to the military authorities. These individuals were not dangerous criminals, however, but refugees, mostly Jewish, many of whom had come to Britain fleeing Nazi oppression. The day’s arrests were reminiscent of the roundups they had narrowly avoided at home in Germany and Austria. Now they were being interned by their supposed liberators, subject to a collective trauma: to be imprisoned by one’s liberator is to endure an injustice of chronology.

In recent months rumors had abounded that a fifth column—a neologism to Britain at the time, now universally understood to refer to traitors living within their country of asylum—had assisted the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. Tabloid newspapers had stoked national paranoia with claims that a similar network of spies lurked in Britain. Hysteria had overcome logic. Most refugees spoke thickly accented English, were unaccustomed to British social norms and would make ineffectual spies. Fifth Columnists were far likelier to come from the ranks of British fascists. As the politician Herbert Delaunay Hughes wrote, pseudonymously, at the time: “It is lamentable how quickly people seem to have forgotten who exactly the refugees are and how it is that they came to this country.”

A widespread ignorance of the true numbers of foreigners to whom Britain had offered asylum hastened the change in public attitudes. In 1940 one poll asked British citizens to estimate the number of refugees who had come to Britain from Nazi Germany in the previous six years. Respondents put the number at anywhere between two and four million. The true figure was just 73,500.

The recent German occupation of France meant an invasion attempt seemed not only plausible but imminent. While many British citizens acknowledged there was injustice in a mass internment policy, they felt that it was nevertheless an appropriate, justifiable measure. On 11th May 1940, one day after he became prime minister, Winston Churchill authorized the arrest of thousands of so-called “enemy aliens.” When Hitler learned of Churchill’s internment policy, he reportedly gloated: “The enemies of Germany are now the enemies of Britain too. Where are those much-vaunted democratic liberties of which the English boast?”

Status and class, those twin armaments of privilege, provided no protection. Nazism had pushed a wave of luminaries toward Britain. Now these Oxbridge dons, surgeons, dentists, lawyers, and celebrated artists were taken into custody. The police arrested Emil Goldmann, a 67-year-old professor from the University of Vienna, in the grounds of Eton College. At Cambridge University, dozens of staff and students were detained in the Guildhall, including Prince Frederick of Prussia, a grandson of Queen Victoria (who, while interned, received food packages from the luxury department store Fortnum & Mason allegedly paid for by the British royal family). That year’s Cambridge law finals nearly had to be cancelled because one of the interned professors had locked away the exam papers, and taken the key.

Many internees were first transferred to transit camps, where conditions ranged from comfortable to, in the case of Warth Mills, an abandoned, decaying cotton mill in the north of England, uninhabitable. On arrival, British soldiers took valuables from the internees— money, wristwatches, cigarettes, writing paper and typewriters—distributing these items among themselves in full view of the looted. Doctors watched, bewildered, as the soldiers pocketed their stethoscopes. Academics argued that they should be allowed to keep their textbooks. Artists pleaded to keep their drawing paper.

For some, this ransacking crowned a brief period that had transformed their view of Britain, and their place within it. At Warth Mills two thousand internees shared a single bathtub, and eighteen water taps. There was no sewerage system in place, and the lavatories amounted to sixty buckets housed outside, beneath an oblong tent. Dr Simon Isaac, a former professor at the University of Frankfurt who had overseen makeshift hospitals on the Russian Front during WWI, wrote that he had never seen a place less fit for the accommodation of human beings. The indignities of isolation from friends and relatives, meagre food rations, lice, and inadequate sanitary arrangements led many internees to draw parallels between the mill and the Nazi detention camps from which they had fled. According to an official Ministry of Information report, two men, both of whom had previously been incarcerated in Nazi camps, died by suicide.

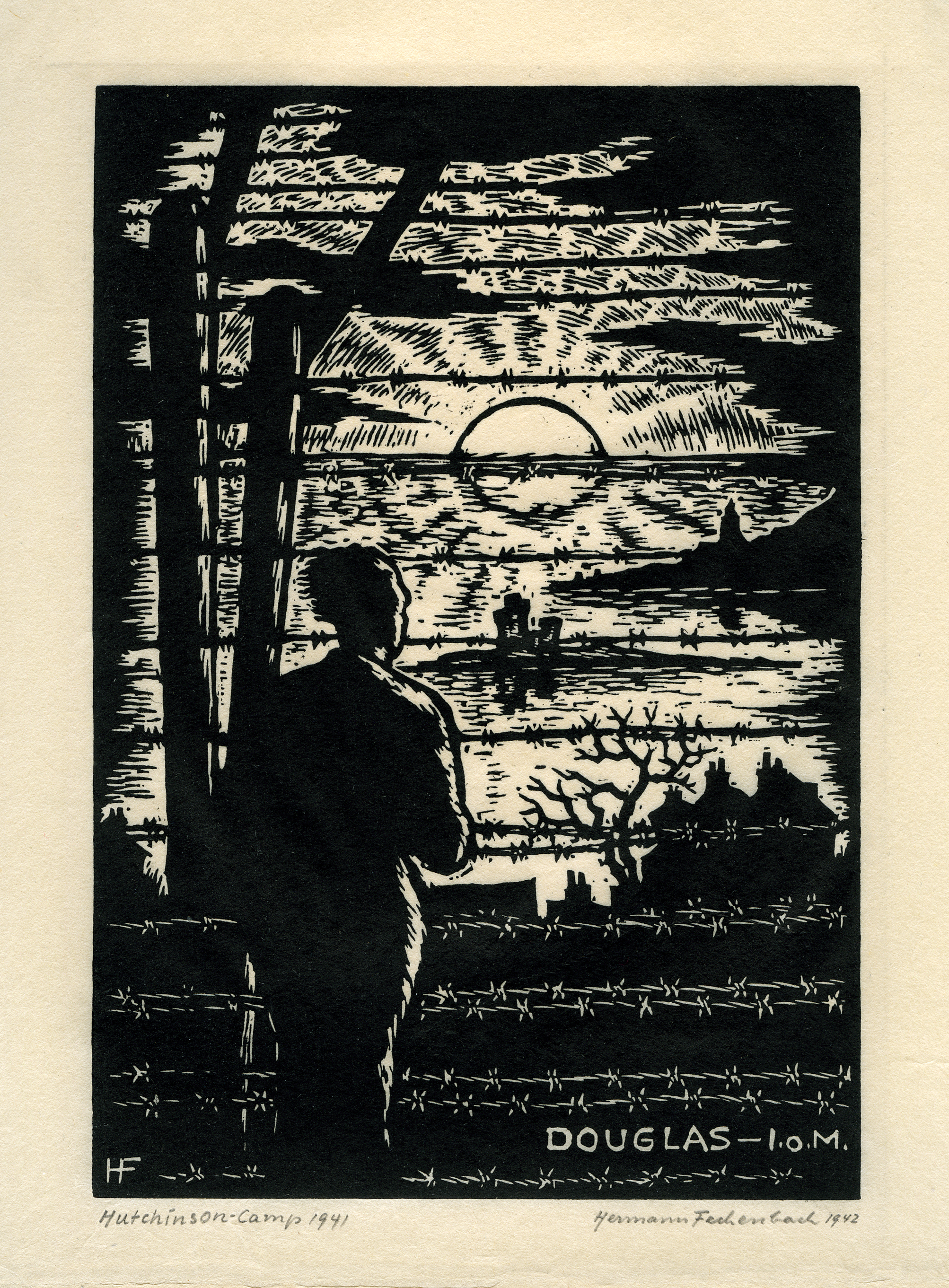

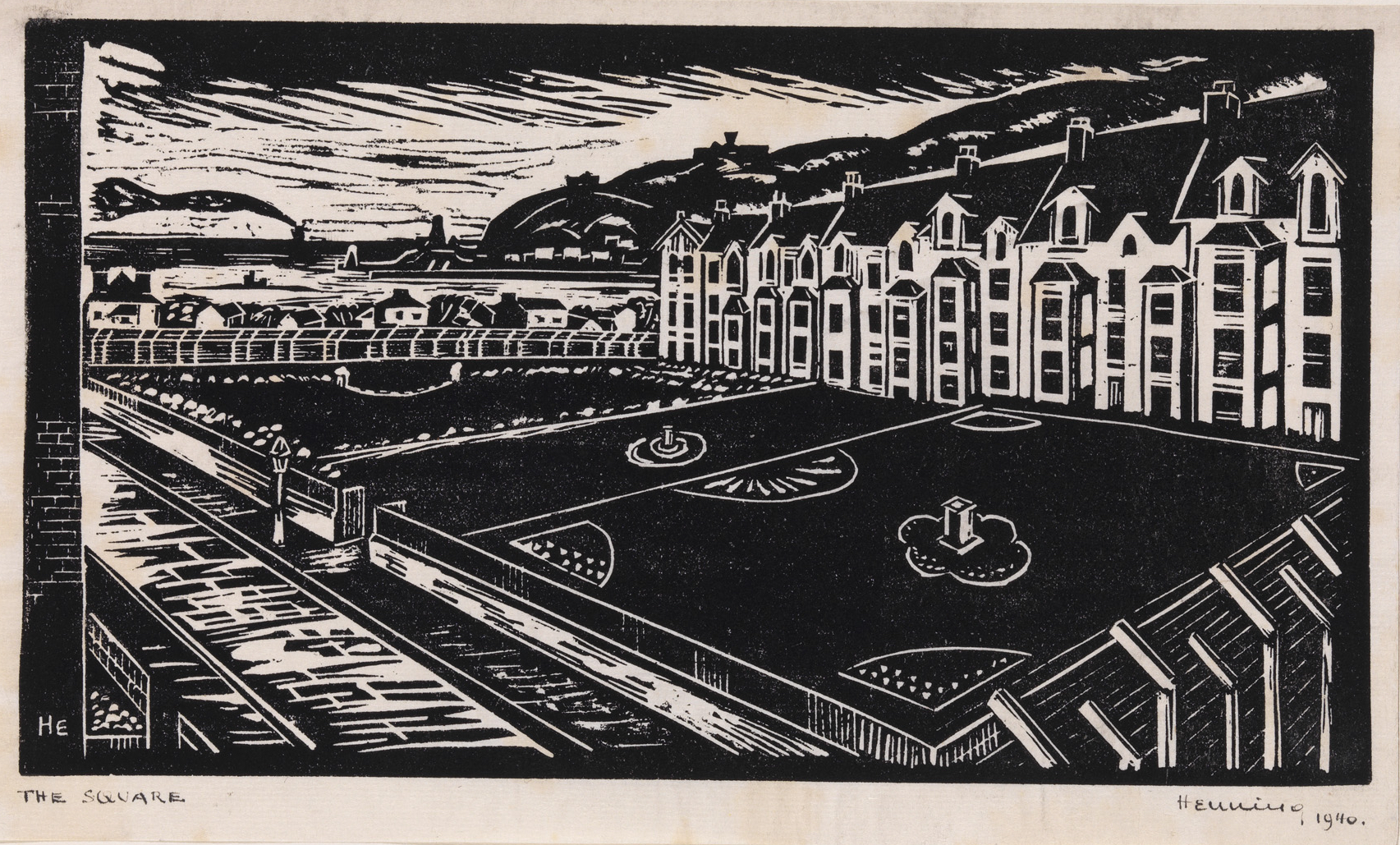

Internees were soon transferred to one of the permanent camps, ten of which were situated on the Isle of Man. One of these camps, ‘P’ Camp, or ‘Hutchinson’, opened on 13th July 1940. In Hutchinson around 1,200 internees were packed in requisitioned boarding houses that bordered a picturesque square, with views leading down to the harbour. For some there was a frisson of an unexpected holiday. The older men better understood the precariousness and uncertainty of their situation—imprisoned without charge or trial, subject to the outrageous accusation of being a member of the regime that precipitated their exile, and with no idea how long they would be held. These were holiday homes, but this was no holiday.

Through happenstance, Hutchinson became home to a dazzling array of luminaries, Nobel-prize-winning professors, lauded composers, award-winning journalists and feted international lawyers—including one who claimed to count the Vatican among his clients. There was Heinrich Fraenkel, journalist and chess-setter for the New Statesman, who was busy writing the book, ‘Help Us Germans To Beat The Nazis’, for Victor Gollancz, from his bed inside the camp. There was the archaeologist Professor Gerhard Bersu, a world expert on Vikings, the music critic Rudolf Kastner who claimed to have discovered the American violinist Yehudi Menuhin, and Walter Neurath, a book publisher who later founded the publishing company Thames & Hudson with the wife of his Hutchinson colleague, Wilhelm Feuchtwang.

The camp’s population included fashion designers such as Otto Haas-Heye, whose designs defined German women’s style in the 1920s, and Harald Marenholtz, a friend to Pablo Picasso, Christian Dior, and Gabrielle ‘Coco’ Chanel, whose clientele at his Mayfair fashion house included Her Royal Highness the Princess Margaret, the Royal Ballet dancer Margot Fonteyn, and the Hollywood actor Vivien Leigh. There were architects, such as Carl Franck, who helped changed the silhouette of the British city, and doctors, such as the eye surgeon Oskar Fehr, who via his pioneering operation to fix a detached retina, changed the course of medicine. And among the camp’s considerable contingent of Oxford and Cambridge academics were world experts in law, philosophy, and history.

Two days after the camp’s opening some men emerged from their boarding houses carrying chairs and ladders which they set up around the terraced lawn. They beckoned passers-by, and, when they had a small crowd, began to hold forth on their specialist subject. Soon the lawn became filled with speakers and their various audiences, like, as one observer put it, a scene from Ancient Athens. A listener could wander freely between subjects, from Greek philosophy, industrial uses of synthetic fibres to Shakespeare’s Sonnets.

Bruno Ahrends, an architect who had, during an illustrious career, designed Berlin’s highly influential modernist housing estates, approached the camp commandant, Captain Hubert Daniel, and requested permission to organise a formal schedule of lectures. Daniel offered Ahrends a room on the first floor of the camp’s administration building. Together with his assistant, the young art historian Klaus Hinrichsen, the pair assigned daily lectures, organised theatre and music performances and, arranged lessons and tutorials for the younger internees to prepare them for the exams they would, hopefully, still be able to sit upon their release.

Professional actors and film directors staged productions of, among others, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Of Mice and Men. The backdrops to these plays were built from scavenged components by the set-designer Este Stern, a frequent collaborator of Max Reindhart and Noël Coward. The artists in the camp, including the famous Dadiast Kurt Schwitters, soon established a semi-exclusive Artist’s Café, housed in a laundry room extension. Schwitters converted his attic bedroom into an impromptu studio. And, on the lawn outside, he offered to sketch passers-by, with prices set on a sliding scale: £3 for a head and shoulders; £4 for head, shoulders, and arms; £5 for a half figure. Meanwhile, the journalists published a fortnightly camp newspaper, featuring news, articles, fiction, and illustrations – edited by Leo Freund under the penname Michael Corvin.

Some internees established a Technical School, and arranged to installation of a speaker system throughout the camp. Codesigned by Dr. Hans Rothfels from St. John’s College, Oxford, and installed by Herman Rahmer, one of the first people to perform with the Theremin instrument, it consisted of 2,700 yards of wire, which fed fifty-three speakers in each house’s dining room, and enabled the broadcast of radio programs from the BBC. The system also enabled the commandant to relay messages from his desk to the entire camp. Captain Daniel warmed to his role and would routinely announce the latest cricket scores to the bewildered internees.

Despite the cultural richness of the camp, depression was rife, as the men waited for news of their loved ones, worried about their businesses, and obsessed over freedom. “Lest this all sounds too rosy a situation,” Klaus Hinrichsen noted, “let me assure you that all these frantic activities were entered into as a means of distraction from the ever-present anger at the injustice… the constant worry about wives and children left without a provider… from the lack of communication and, of course suffering from the cramped living conditions and the lack of freedom.”

In London campaigners such as the MP Eleanor Rathbone, Helen Roeder, secretary of the Artist’s Refugee Committee, and the Quaker Bertha Bracey secured books to open an impromptu library in the camp, where Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca proved to be the most borrowed titles. In government, attitudes to the mass internment policy had begun to shift, hastened by the news of the sinking of the SS Arandora Star, when 650 men, including German, Austrian, and Italian refugees en route to Canadian internment camps, were drowned after a U-boat torpedoed their liner. It was shipping disaster with one of the gravest losses of life of the Second World War. The economist John Maynard Keynes, an adviser to the government, claimed that he had “not met a single soul, inside or outside government departments, who is not furious at what is going on.” Undoing the mess, however, proved time consuming and complex.

In the autumn of 1940, the British government released a white paper outlining several categories under which internees could apply for release. Those who were too young or too old, too infirm, or who already had permits to work in positions of national importance could apply to be freed. Artists, writers, and musicians were not included until later revisions, and had to prove they had achieved distinction in their chosen field. As Helen Roeder, secretary of the Artists’ Refugee Committee, put it: “Do you think [the criteria could] be stretched to include the poor souls who have been too busy being hunted to achieve distinction in the arts?”

In the early months of internment, the fact that so many brilliant men of self-evidently anti-Nazi beliefs had been interned highlighted the absurdity of the situation. As the autumn nights grew longer, however, any sense of perverse delight clotted into dismay and bitterness as, one by one, the camp emptied of celebrated individuals. “The weeks until Christmas and after seemed to be just one endless gloom and depression,” the lawyer-turned-painter Fred Uhlman wrote. “Every day I waited in fear and hope till the names of the released were announced, only to crawl back to my room too miserable to eat.”

By March 1941, 12,500 internees had walked free, representing almost half of those who had been interned the previous summer. Most eminent individuals quickly found a way out of the camps, but many of those without connections were left to languish, some for more than three years. While the internees were relatively comfortable, internment was a near-constant misery for most, one that, as the Oxford academic Paul Jacobstahl wrote, caused a “trauma.” At least fifty-six internees died in internment on the Isle of Man, many to suicide.

After the war few went as far as Tristan Busch, a former internee who described the British policy as a “war crime”, but it is indisputable that the hasty measures heaped unhappiness and anguish upon thousands of people already enduring the ordeal of fleeing their previous lives. Only a single sentence spoken by Sir John Anderson in the House of Commons on 22 August 1940, months before most of Hutchinson’s internees were freed, provided something approaching an apology: “Regrettable and deplorable things have happened,” he said, as if the cruelties of internment had been the result of natural phenomena, and not a series of deliberate choices.

Unlike the wartime internment of Japanese Americans in the United States, which is an episode of ongoing lament, the British internment of so-called ‘enemy aliens’ has been mostly kept separate from the prevailing story Britain tells itself about its wartime character. There has been no attempt to repair the damage by the British authorities in failing to distinguish between refugees and “enemy aliens” ––a dehumanizing term that, in 2021, the U.S. government pledged never again to use. The battle between a nation’s responsibility to help those in need and to maintain national security persists in every age, every generation. But the notion of the refugee who is not who he or she claims to be is an enduring story that can be easily used to justify institutional cruelty or overreach. While the context and detail shifts, the debate remains the same. Each successive generation must answer the question: How far can we go in the rightful defence of our values, before we abandon them along the way?

Adapted from Simon Parkin’s The Island of Extraordinary Captives: A Painter, a Poet, an Heiress, and a Spy in a World War II British Internment Camp

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com