This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Not long after the Gulf nation of Qatar was awarded the rights to host the 2022 World Cup soccer championships, Surendra Tamang hatched a plan to go.

He had heard that Qatar was recruiting many other Nepali laborers to work in Doha building the stadiums and related infrastructure projects. So in 2015 he took out a loan to cover the recruitment agency’s fees and applied for a construction job. He figured he would work up until the World Cup, sending his earnings back home while putting enough aside to buy a ticket to the final match. Only then would he go back to Nepal, triumphant, rich (or at least richer than his neighbors), and with a World Cup T-shirt featuring Argentina’s Lionel Messi, his favorite player.

Instead, in October 2021, he was sent home with a mysterious, crippling ailment that his employers dismissed as gastritis—chronic indigestion—and claimed had nothing to do with the arduous conditions at his work site. By the time he arrived at a Kathmandu hospital in debilitating pain, both his kidneys had given out, wrecked by working long hours of hard labor in punishing heat, according to his doctor. “I used to have dreams,” Tamang says from his hospital bed at the dialysis clinic of Nepal’s National Kidney Center. Now 31 and with no potential kidney donors on the horizon, he will likely be on dialysis for the rest of his life, forced to watch the World Cup on his phone.

Every four years, for four weeks, World Cup host countries open their doors to millions of fans, investing national pride in ever more fantastic stadiums purpose-built for the world’s most popular sport. Qatar has spent more than $200 billion on construction that offers a preview of future technologies, from outdoor air-conditioning to retractable roofs. But these games also offer a sobering preview of another future, one in which the kinds of record-breaking heat waves that roasted Asia, Europe, and North America this summer are no longer extreme events but seasonal norms brought about by a changing climate. Those rising temperatures will change the future of work, making outdoor labor increasingly dangerous to human health in the hottest parts of the year, across most of the globe.

Read More: Climate-Proof Towns Are Popping Up Across the U.S. But Not Everyone Can Afford To Live There

This year, the World Cup will start on Nov. 20, five months later than usual, to spare players and fans the worst of the region’s blisteringly hot summer. But preparations for the tournament—a building boom in one of the hottest places on the planet—took more than a decade. To make it happen, Qatar relied on a global supply chain of laborers willing to work in any conditions—a desperation fueled in part by the impacts of climate change. Qatar’s 2 million-strong foreign workforce, which makes up more than two-thirds of the population, is largely recruited from Nepal, India, and Bangladesh. Thousands of those workers have died over the past decade, many because of poor working conditions made more perilous by excessive heat.

Doha’s daily high temperatures are now 1.4°F warmer in summer, on average, than when the World Cup was announced 12 years ago. The Middle East is one of the fastest-warming places on the planet, but the rest of the world is not far behind. By 2100, temperatures could rise to the point that just going outside for a few hours in some parts of the Middle East, Africa, and Asia will exceed the “upper limit for survivability, even with idealized conditions of perfect health, total inactivity, full shade, absence of clothing, and unlimited drinking water,” according to a 2020 study in Science Advances. Construction work under those conditions will be impossible.

In contemporary Qatar, however, workers can still be protected from the effects of excessive heat. That so many were not over the past decade is a stain on the country’s legacy. But it is also a learning opportunity. The World Cup spotlight forced drastic changes in labor regulations that, since their implementation last year, have made Qatar a world leader in heat protection and a useful laboratory for a better understanding of what works—and does not work—in an era of climate change. Already the U.N.’s International Labor Organization (ILO) calculates that the increase in heat stress will lead to global productivity losses equivalent to 80 million full-time jobs by 2030. Meanwhile, recent heat waves have catalyzed international campaigns to get heat recognized as an occupational hazard, and labor activists as well as government entities are pushing for stronger regulations and laws to protect outdoor workers, whether they’re building stadiums, harvesting crops, or sweeping streets. Qatar could end up providing the template.

Surendra Tamang arrived in Qatar in the late spring of 2015. Despite the vivid descriptions by friends recently returned from the Gulf, he was unprepared for Doha’s furnace-like heat. One of his first tasks at the Doha Oasis construction site, the luxury residential and entertainment complex in downtown Doha that was his place of employment for six years, was in scaffolding—an assignment that required a heavy harness and a hard hat, which sent rivulets of sweat cascading down his body within minutes of going outside. When the summer reached its zenith and temperatures approached 112°F (44.4°C), he and his fellow laborers worked on, taking a break only for a few hours at lunch to avoid the hottest part of the day. As the years passed, he grew accustomed to the bloody noses, headaches, muscle cramps, and vomiting that accompanied work in Qatar’s May-through-September summer season. He regularly fought off dizziness and witnessed several colleagues collapse from heat exhaustion. He did too, a few times. TIME reached out to Tamang’s employer, Redco Construction Al Mana, as well as the Doha Oasis, but received no response.

Summers in Qatar are not just hot, they are also humid, a dangerous combination. The only way the human body can cope with heat is by producing sweat that cools as it evaporates. The higher the humidity, the less evaporation, leading to a rise in core temperature, and eventually organ failure. Scientists use an index called the wet-bulb globe temperature, or WBGT, to assess the impact of heat and humidity. Developed by the U.S. Marines in the 1950s, it combines temperature, humidity, and solar-radiation measurements into a single number expressed as a temperature. A WBGT above 95°F (35°C) is considered to be the “threshold of survivability.” A reading of 90.5°F (32.5°C) is considered the redline for heat injury for any kind of activity. That’s the equivalent of 93°F at 50% humidity—a typical late summer afternoon in Qatar.

Read More: Inside Facebook’s African Sweatshop

In 2007, Qatar banned outdoor work between 11:30 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. during the summer; as a result, construction companies divided the work into early-morning and late-afternoon shifts. Tamang got the morning shift, starting his day at 4 a.m. so he could eat breakfast and prepare his lunch at the company-run worker colony—where up to 70,000 workers employed by various contractors eat, sleep, and spend their time off—before taking a shuttle bus to the work site an hour and a half away. Still, the early start gave him no relief—the temperature was slightly lower, but the humidity surpassed 70% in the morning hours, driving the WBGT even higher.

At Tamang’s construction site, workers were doing heavy physical labor in heat conditions that even the Marines would consider dangerous. Like most of his co-workers, Tamang pushed through the headaches and dizzy spells, worried that if he took too many breaks, his employer would dock his pay or send him back to Nepal. He knew he needed to stay hydrated, but the bottles of cold water sold nearby cost the same as a Coca-Cola, so he opted for soda. When he was working on high scaffolding, he tried not to drink anything at all, so he wouldn’t have to climb down to use the toilets.

Over time, Tamang’s increasingly frequent dizzy spells, bouts of nausea, muscle weakness, and fatigue got to the point where work became impossible. He went to the construction company’s doctor, who gave him medicine for gastritis and told him to avoid spicy foods. Still, his symptoms persisted, and the company eventually moved him to desk work in an air-conditioned office, but by then it was too late. At follow-up appointments, company doctors warned him about his blood pressure, but he says no one ever tested for kidney disease. His employer ordered him back to his dormitory for two weeks without pay, to regain his strength. When he didn’t recover, the construction company terminated his contract and sent him back to Nepal.

Tamang had been sending the bulk of his $400-a-month salary home to his family, part of a $10 billion river of remittances that flows into Nepal every year from Nepali migrant workers employed abroad; it accounts for nearly a third of the nation’s GDP. For farming communities like Tamang’s, the transfers have become an essential buffer against the floods and drought caused by climate change that are making agriculture increasingly unreliable.

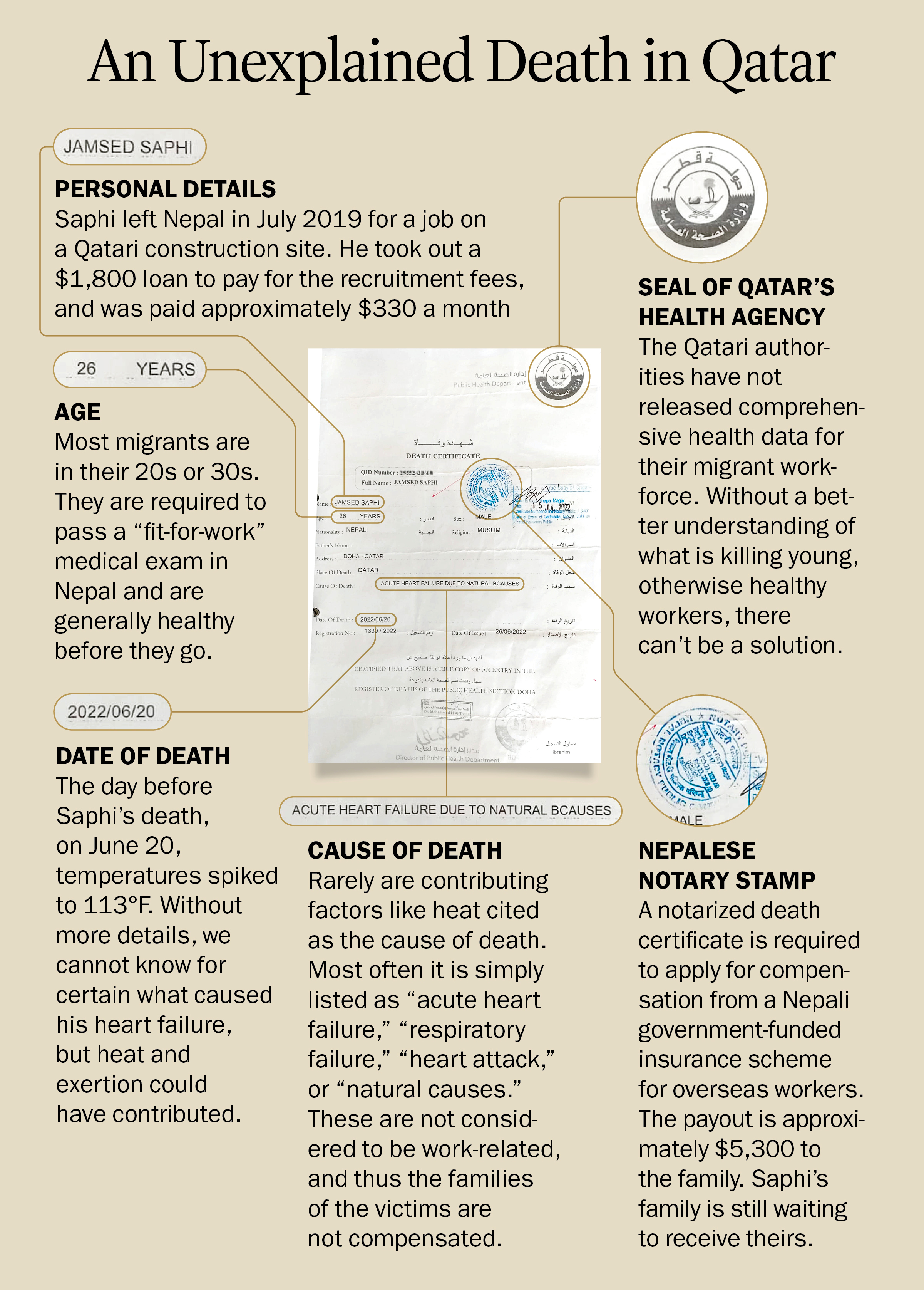

In June 2022, Indrajit Mandal, a 22-year-old rice farmer in the southern Nepali village of Nagarain, paid a recruiter the equivalent of $1,200 to secure a job in Qatar. (Nepal outlaws recruitment fees for foreign labor contracts; the recruiter says he took only a “small commission.”) “People are coming back from Qatar with kidney disease and heart attacks,” says Indrajit. “But I am ignoring this because we have no choice.” His uncle Kripal Mandal, who had been working construction in Qatar for 12 years, died this year of a heart attack at age 40, and Indrajit suspects it was caused by chronic exposure to extreme heat. Death certificates for deceased migrant workers in Qatar frequently cite “cardiac arrest” as the cause, suggesting their deaths were not work-related. But the reality is that most of these people are young and healthy; indeed, all workers must pass a basic “fit for work” health screening before obtaining a Qatari work visa. And so the high rate of cardiovascular disease listed as the cause of death among migrant workers in the country points to some other cause of the problem.

According to a 2019 study in Cardiology that analyzed more than 1,300 Nepali migrant-worker deaths in Qatar from 2009 to 2017, nearly half were attributed on death certificates to cardiovascular disease, a rate that far exceeds the 15% global norm for men in a similar age bracket. When the figures were broken down by season, death rates due to heart attack went down to 22% in the winter and leaped to 58% in the summer. Many of the deaths occurred during periods when the WBGT exceeded 87°F (31°C), leading the authors to conclude that at least 200 men likely died from heat injuries sustained by working, even though the cause was listed as cardiac arrest. Qatar’s labor law requires employers to pay compensation only if a death is work related, which is usually, narrowly interpreted as taking place at the work site. A heart attack that occurs in worker accommodations at the end of a strenuous day, as happened with Indrajit’s uncle, doesn’t qualify. But even relatively lower levels of heat stress can cause severe problems over time, especially if accompanied by chronic dehydration.

When nephrologist Dr. Rishi Kumar Kafle launched Kathmandu’s National Kidney Center 25 years ago, he expected to serve older patients suffering from the kind of kidney problems that accompany age and chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension. But over the years, his patient numbers increased, and their average age went down. Most of his younger patients had one thing in common: recent employment abroad. Today, he estimates that returnees from the Gulf countries make up 10% of his caseload. “These young men coming back from the Gulf don’t have diabetes; they are not hypertensive. They are healthy. Then suddenly they develop kidney failure. It means that there is something in the Gulf which makes certain young people sick.” A number of factors are at play, he says: continuous dehydration, bad diet, stress, and excessive use of painkillers to dull the aches and pains of hard labor. But the main underlying issue is heat.

The solutions are fairly simple: hydration, rest breaks, and respite from the sun. Trials with sugarcane workers in Nicaragua have shown that when laborers are allowed to take frequent water breaks in the shade, incidents of kidney damage go down dramatically and productivity goes up, according to a 2020 study published in the journal Occupational and Environmental Medicine. “Water. Rest. Shade. It’s not rocket science. It’s not expensive. And it saves lives,” says Jason Glaser, a lead author of the study and the director of La Isla Network, the nonprofit occupational-health organization that pioneered the worker-safety plan.

Read More: Extreme Heat Makes It Hard for Kids to Be Active. But Exercise Is Crucial In a Warming World

Three years after Qatar started construction on the World Cup stadiums in 2011, the International Trade Union Confederation published an exposé warning that some 4,000 migrant workers would likely die before the opening match as a result of the country’s exploitative labor practices. The projections were based on a tally of migrant worker deaths in 2012 and 2013 released by the Indian and Nepali embassies, and was supported by similar reports from Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, which described squalid dormitories, grueling work hours, unpaid wages, and dangerous health-and-safety practices in the country. A February 2021 investigation by the Guardian tallied more than 6,500 worker deaths in Qatar since the awarding of the World Cup, firmly laying the responsibility at the feet of FIFA, the international soccer federation that governs the event.

But Qatar’s building boom goes far beyond the World Cup.

More than 3,750 construction projects were completed in 2020, and thousands more are ongoing. Nearly every block beyond central Doha features a newborn edifice swaddled in scaffolding; construction cranes compete with skyscrapers as the dominant feature of the city skyline. While the frenetic pace of development may have been galvanized by the awarding of the World Cup, not all of it is directed toward hosting games or catering to fans. Ever since the launch, in 2008, of the Qatar National Vision 2030, the government has worked to transform the gas-rich nation into a business and transportation hub for the region, diversifying the economy away from fossil fuels and building the city-state into a modern metropolis with the addition of hundreds of office towers, hotels, residential blocks, entertainment centers, and the necessary infrastructure to keep the city thriving.

The irony is that for all the focus on World Cup stadiums, the most egregious abuses happen at private construction projects like Tamang’s that have little to do with soccer. Qatar’s Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy, in charge of World Cup preparations, employed only 35,000 workers at its peak, accounting for less than 2% of the country’s migrant labor force over the past decade. Some of those non-World Cup-related work sites are well regulated, but others are not. TIME was granted permission to visit one privately run work site, a luxury residential complex that won’t be completed until long after the World Cup is over, accompanied by officials from the Ministry of Labor. The workers, interviewed in the presence of their supervisors, appeared content with the regulations governing heat protections. They complained of the heat—112°F (44°C) at 9 a.m. on the day we visited—but said that they were allowed to take breaks in cooled rest areas when it got too hot; that their supervisors frequently passed out water and reminded them to hydrate; and that if the WBGT index went past a certain point, outside work would stop entirely. Laborers from other sites that TIME was not allowed to visit described the one we did as an exception, not the rule. One Nepali health-and-safety supervisor, who has been employed on Qatari construction sites since 2002, and who asked not to be named for fear of losing his job, says conditions “are improving, but still not fast enough to save lives.”

In May, several labor and human-rights organizations demanded that FIFA set aside $440 million—the same amount it hands out in World Cup prize money—for the welfare of workers who suffered human-rights abuses in Qatar during preparations for the 2022 World Cup. The campaign has received global support, and FIFA told Amnesty it was “considering” the proposal. But even if FIFA agrees to some sort of compensation scheme, differentiating between World Cup workers and those laboring on construction sites that may or may not have been spurred on by the World Cup announcement will be difficult.

According to an assessment released by Building and Wood Worker’s International, a labor union based in Geneva, construction sites run by the Supreme Committee “ensured a higher than industry level of protection … including new methods for monitoring and mitigating the effects of heat stress.” Mahmoud Qutub, the Supreme Committee’s executive director for workers’ welfare and labor rights, says every World Cup work site offered cooled rest areas and mandatory hydration breaks. They also closed during the hottest part of the day in summer, and laborers were given specially designed cooling suits. They were also allowed to take breaks whenever they felt the need. These health-and-safety protocols, Qutub says, reduced “workplace-related” fatalities among the overall World Cup construction effort to only three across 10 years, none due to heat. While those numbers are backed by the U.N., they reflect an overly strict definition of work-related. The Supreme Committee’s own annual reports cite 36 non-work-related deaths caused by “respiratory failure,” “heart attack,” “natural causes,” a shuttle-bus accident on the way to a work site, and one case of suicide. That said, even if those deaths are included, World Cup construction-site fatality rates are far lower than Qatar’s work-site fatality rate as a whole, demonstrating that workers can be protected when it is made a priority.

In 2019, the government made it a priority. Hounded by condemnations from the press, international labor unions, and human-rights groups, Qatar brought in representatives from the ILO and other experts to undertake a comprehensive study of the country’s labor conditions, with the goal of implementing reforms. They spent several summer weeks on Qatari work sites monitoring labor conditions. Some workers agreed to ingest electronic devices that could record body temperatures and dehydration levels, to help researchers understand the impacts of high heat and humidity, and tested mitigation efforts like cooling suits, hydration solutions, work-rest ratios, and air-conditioned break rooms.

At the end, the researchers suggested Qatar’s Ministry of Labor add an extra hour and a half to the daily midday outdoor work ban in summer while expanding the “summer” schedule an additional four weeks—representing a reduction of 586 work hours a year. They advised companies to establish cooled rest areas and implement hydration protocols, and recommended setting a maximum WBGT threshold of 89.7°F (32.1°C), at which point all outdoor work would cease, no matter the time of day or year.

Read More: How Qatar’s New Cool-Tech Gear Helps Workers in Extreme Heat

That’s still too high, according to some heat researchers, but it’s a workable compromise, according to Andreas Flouris, the founder of the University of Thessaly’s FAME laboratory, which Qatar brought in to the country to assess its work environment. “32.1°C keeps workers safe,” says Flouris. “At the same time, it keeps the economy humming, because being unemployed also hurts worker health.” His team also recommended that all outdoor workers undergo annual health screenings so that those with hypertension, diabetes, or other chronic conditions could be identified, diagnosed, and moved to less strenuous positions. Further reforms, suggested by Building and Wood Worker’s International and the ILO, ended the kafala sponsorship system that tied workers to their employers and did not allow them to change jobs or leave the country without permission. Qatar turned those recommendations into law in May 2021. Almost overnight, a country synonymous with worker oppression adopted the world’s most progressive heat-protection strategy. Anecdotally, Qatar’s new policy has been transformative. According to the ILO’s annual report on Qatar, hospital admissions to health clinics for heat-related disorders dropped from 1,520 in the summer of 2020 to 351 in the same season of 2022.

But government data on worker deaths and injuries, both before and after the implementation of the new law, are nonexistent, unavailable to researchers, or so vague as to be useless. Qatar is sitting on a gold mine of data that could be used to establish and refine heat-protection policies for workforces around the world, says Flouris, but so far it is not willing to share it. Doing so would expose past mistakes, to be sure, but it could prevent future deaths. “Qatar has the most amazing natural laboratory you can think of. If you can protect workers there, you can protect them anywhere,” says La Isla Network’s Glaser. “You look like a hero when you own it. Qatar could say, ‘We screwed up. Nobody has been doing this right. We’re gonna take the lead to make sure that what happened here never happens anywhere else.’”

Qatar’s Ministry of Labor shut down more than 450 work sites for violations of its new heat-protection policy this summer. It’s a sign of effective monitoring, but the ministry has no enforcement capacity, so violators are often back in operation within days. Nor does the government have the capacity to inspect every work site on a frequent enough basis to ensure worker safety, says Ambet E. Yuson, the general secretary of Building and Wood Worker’s International.

The most effective way to enforce the new policy would be to empower workers to stand up for the rights it now guarantees. So far, it’s not looking good. Fifty-six migrant laborers were arrested or deported for protesting unpaid wages in August, says Yuson. “If workers that haven’t been paid a salary for seven months are deported for complaining, what does that say about workers being willing to stand up for the proper implementation of heat protections on their work sites?”

Tamang now believes that if he had worked on a World Cup stadium project, instead of a luxury hotel, he probably would have made it to the final. The better health outcomes at sites that adhered to strict heat-protection protocols prove that productivity and protection can go hand in hand, says the Supreme Committee’s Qutub. The question now is whether worker health will continue to be prioritized when the last World Cup fan goes home and the spotlight turns away from Qatar’s migrant labor force.

Tamang is skeptical. Back in his bed at Nepal’s National Kidney Center, he listens to messages from friends who stayed behind in Qatar to work on other construction projects, as he waits for his dialysis appointment to end. “It’s disastrous here,” says a former roommate, complaining of unpaid wages, terrible work conditions, and abusive behavior. “I’m not surprised,” says Tamang. “I was expecting that kind of message.”

—With Reporting by Ramu Sapkota/Janakpur; Sweta Koirala/Kathmandu; and Emily Barone, Leslie Dickstein, Anisha Kohli, and Simmone Shah/New York

Correction, Nov 7

The original version of this story misstated the date of Qatar’s first law banning midday summertime working hours. The ban started in 2007, not 2018.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com