A sudden and surprising spike in European exports of washing machines, refrigerators and even electric breast pumps to Russia’s neighbors is raising concerns among officials the trade boom may be helping Vladimir Putin’s war machine in Ukraine.

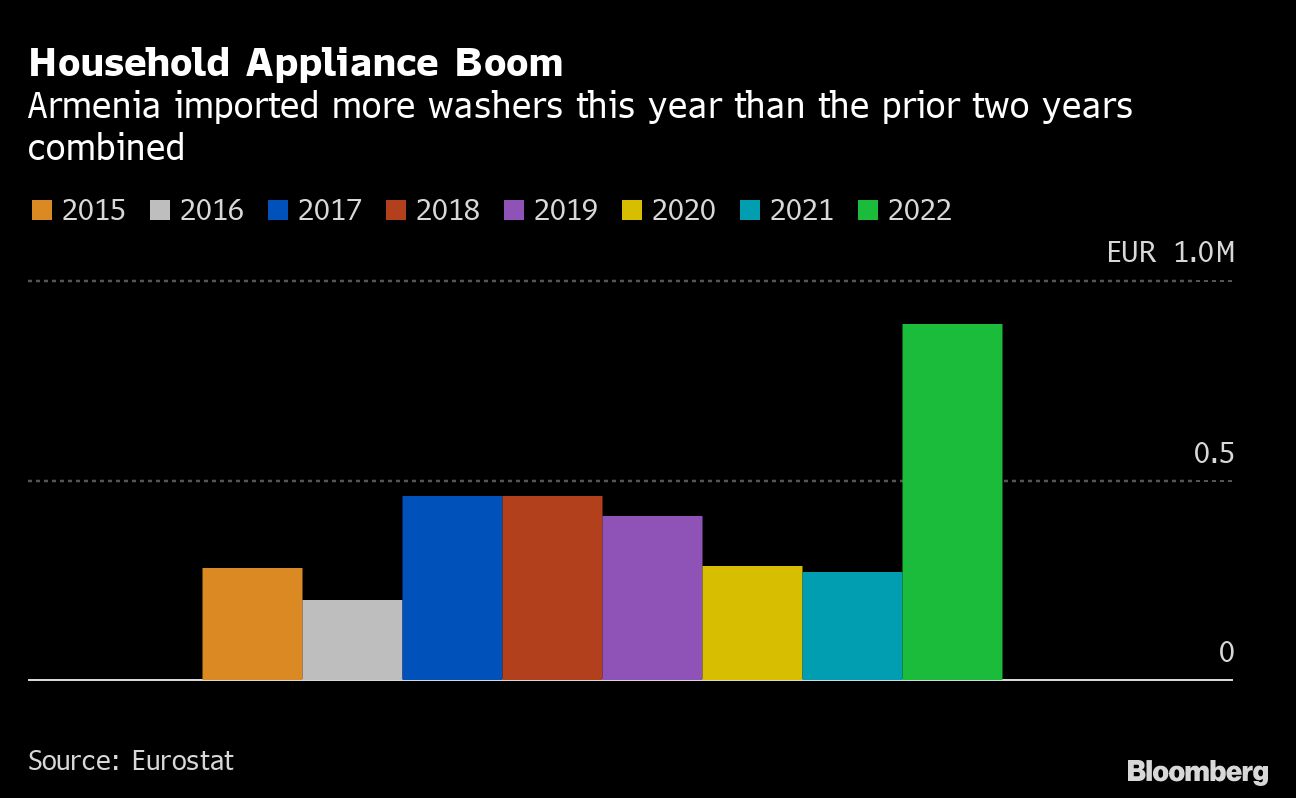

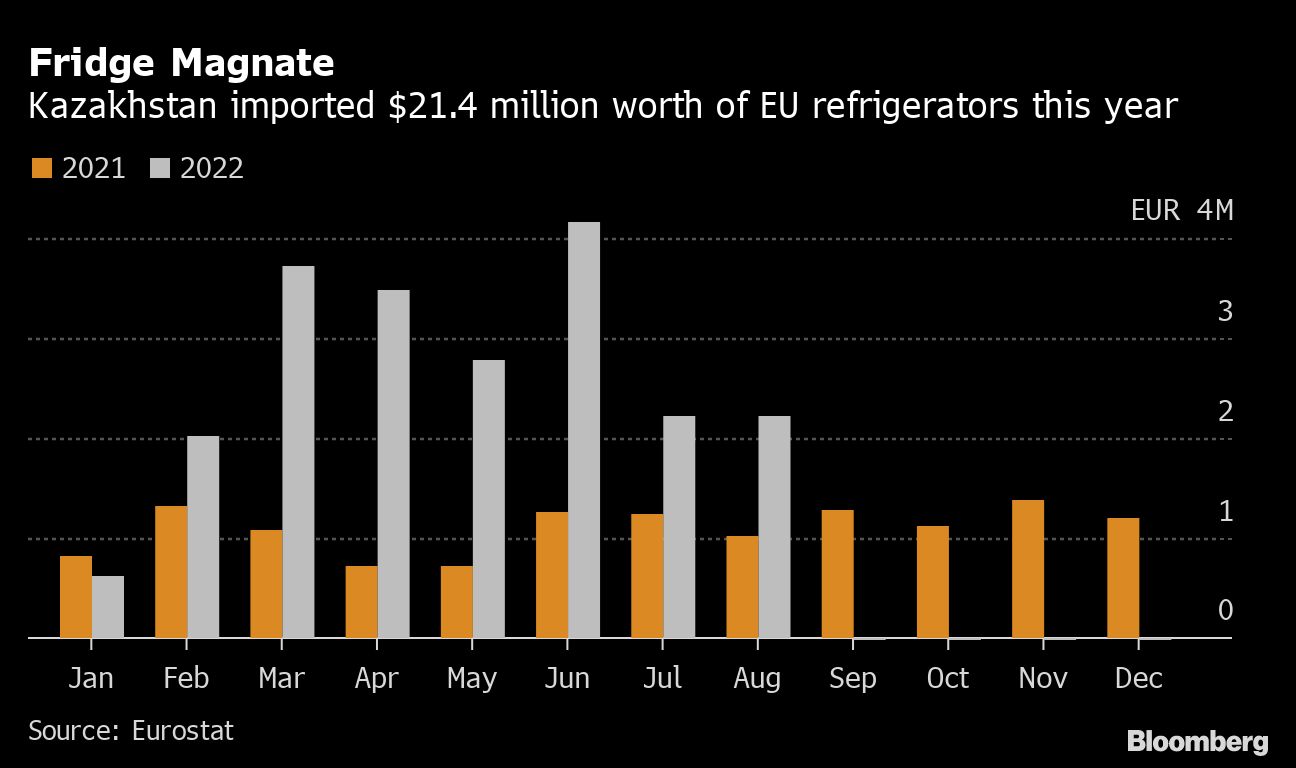

Armenia imported more washing machines from the European Union during the first eight months of the year than the past two years combined, according to data compiled by Bloomberg from the EU’s Eurostat database. Kazakhstan imported $21.4 million worth of European refrigerators through August, more than triple the amount for the same period last year.

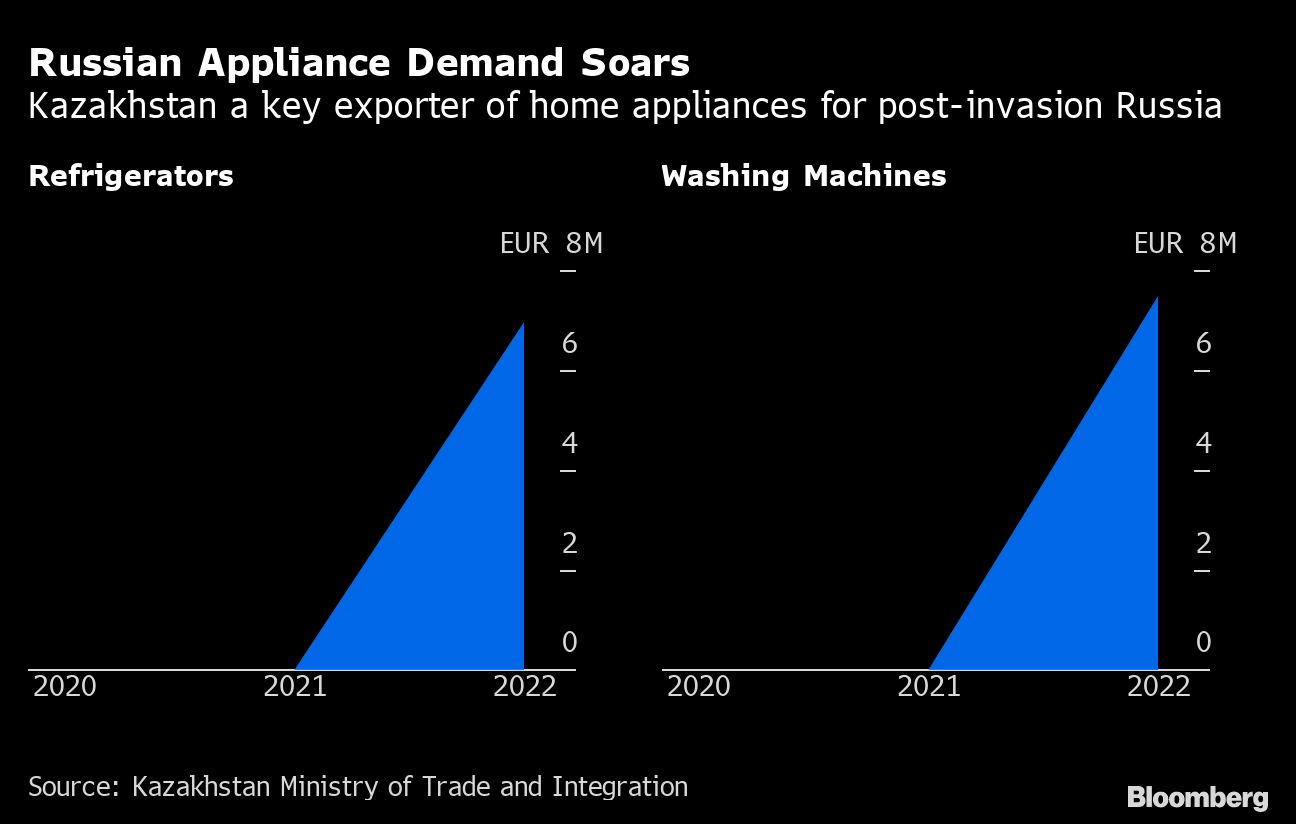

Kazakh government data meantime show a jump in refrigerators, washing machines and electric breast pumps being shipped into Russia.

Some trade via Eurasian states into Russia may be opportunistic businesses making up for shortfalls of imports from elsewhere, or for Russian companies to break up the appliances and use components and semiconductors in civilian manufacturing.

But European officials familiar with the figures say they worry at least some of the goods and their components may be finding their way into military use, and are closely tracking the rise in exports to countries on Russia’s periphery.

Officials in Europe have already said publicly they have seen parts from refrigerators and washing machines showing up in Russian military equipment such as tanks since its invasion of Ukraine. People familiar with the assessments said it was quite possible that components and microchips from other household goods were being used for military purposes, too, even if mostly in relatively low-grade equipment.

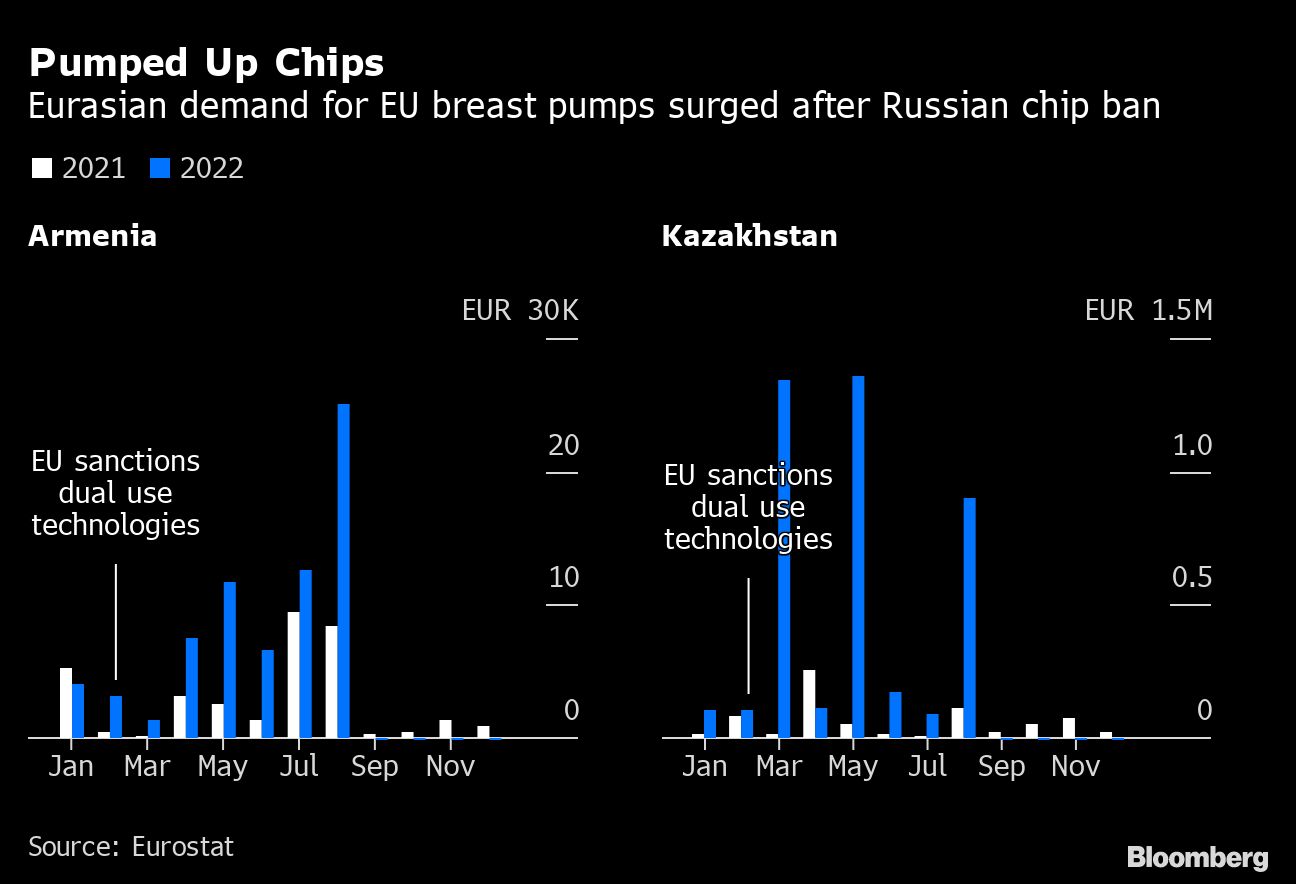

The trade data show for example that EU exports of electric breast pumps to Armenia nearly tripled in the first half of 2022 versus the prior year, despite a 4.3% drop in the Armenian birth rate. Likewise, Kazakhstan’s demand for breast pumps from the EU soared 633% in the first half of 2022 even though the national birth rate fell 8.4% during the same period.

Putin’s war has seen Russia hit by sanctions on almost every sector of its economy, depriving it of imports including chips and other components it has long relied on for basic military equipment like radios and guns through to more sophisticated weapons including missile systems, fighter jets and submarines.

Authorities in Moscow stopped publishing trade figures after the invasion of Ukraine. Still, Russian demand for electric breast pumps from Kazakhstan more than doubled during the first eight months of the year versus all of 2021, according to Kazakhstan government data. The country also shipped $7.5 million worth of washing machines to Russia so far in 2022 — versus nearly zero the previous two years. Its exports of refrigerators to Russia have surged ten-fold versus the prior year.

“Even highly sophisticated Russian weapons systems are often built with run of the mill microelectronic components found in a range of commercial goods,” said James Byrne, director of Open Source Intelligence and Analysis Research at the Royal United Services Institute, a UK think tank. “It’s entirely possible that Russia’s military industrial complex is importing commercial off-the shelf goods to cannibalize for parts.”

Assessing the final destination and the use for the household goods is complicated. Armenia, Kazakhstan and Russia are all in the Eurasian Economic Union, which means there are no customs borders between them. European companies may not want to ship directly to Russia even if their products are not sanctioned, given the optics of being seen to do business with the country right now. They also may not be aware their goods are being sent onto Russia.

European officials say targeting trade in household appliances is difficult, as those items and their so-called sub-threshold components are often not sanctioned. That’s even as the EU has recently introduced new powers that allow it to sanction entities outside the bloc if they help European companies evade its restrictive measures.

Kazakhstan has vowed to not help Russia circumvent sanctions and there is no evidence the government is aiding Moscow to do so. Officials in both Armenia and Kazakhstan did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said last month the Russian military was using chips from dishwashers and refrigerators in its military hardware because it was running out of semiconductors. The Biden administration made a similar claim earlier this year, citing reports of parts that had been found in captured Russian tanks in Ukraine.

It isn’t clear exactly which components might be salvaged from household goods, although they generally all contain microchips. And without workarounds for foreign parts, Russia could find its ability hindered to check Ukrainian military advances on the ground, shaping the course and outcome of the war.

Read more: Ukraine Has Been Using Elon Musk’s Satellites And Russia Is Not Happy About It

European Commission spokeswoman Miriam Garcia Ferrer said the bloc was watching trade flows to identify where sanctions against Russia might be skirted. The commission also monitors “the items used by the Russian army in Ukraine based on forensic analysis of the debris of the remnants of destroyed Russian weapons,” she said.

She added low key components from washing machines or refrigerators are commercially available in many countries and regions and where the EU can identify items that are being used in Russian weapons it considers extending trade restrictions to them. For example a number of electronic components were sanctioned under the latest measures adopted earlier this month, Garcia Ferrer said.

After more than eight months of high-intensity warfare, Russia has sustained substantial equipment losses. US and European officials also say Moscow has run down its stockpiles of key weapons systems, such as high-precision missiles. Ukraine, by contrast, continues to draw on supplies of modern arms from its allies that, together with other advantages such as a ready supply of motivated recruits, has transformed the balance of forces on the battlefield.

Bloomberg News reported earlier in October that Russia had tried for years to reduce its reliance on imports for a vast array of its military equipment — and an internal review in 2021 found it was falling short on almost every metric.

Read more: Ukraine Wants to Use Russian Assets to Rebuild. Experts Think It’s Risky

The US has pushed since the war broke out to cut off Russia’s supplies of semiconductors. “One of the things I’ve been able to do, and I make no bones about it, because of — with Russia’s activities, we have curtailed their ability to access some of this stuff,” President Joe Biden said on Thursday.

“They’re not able to rebuild those devastating weapon systems to take out those civilians in Ukraine as well,” he said. “Not a joke. It makes a big difference. These things matter, and they matter a great deal.”

Other countries that Russia regards as partners, such as China, have largely remained reluctant to supply it with semiconductors and key components even if they have not signed up to the sanctions imposed by the US, Europe and others.

Still, Russia had long experience in evading sanctions to supply its military during the Soviet era, through smuggling and espionage.

An August study of 27 advanced Russian weapons systems by RUSI found 450 unique foreign made components, a majority of which were manufactured in the US, and most of the rest in Europe and other nations that have imposed sanctions on Russia.

“Common components used in weapons platforms such as microprocessors, analog-to-digital converters, field-programmable gate arrays and micro controllers can also be found in a wide range of commercial goods such as televisions, cars, computers and cameras,” said Byrne, one of the authors of the RUSI report.

At the same time, a global semiconductor shortage “has reportedly caused many firms struggling with their semiconductor supply chain to cannibalize goods for their microelectronics.”

One European official noted that Russian troops were also systematically seizing and looting household appliances in Ukraine. The theft has been widely documented, but it isn’t clear how much has been taken for state use or personal use.

–With assistance from Sara Khojoyan, Jorge Valero, Nariman Gizitdinov and Akayla Gardner.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com