For Amazonian land activist Erasmo Theofilo, this year’s Brazilian presidential election is the most important in the country’s history. But he could not vote during the first round on October 2 because he and his family were in hiding from assassins.

Since Jair Bolsonaro came to power in 2019, this is the fourth time that Theofilo, his wife Nathalha, and their four small children have had to go into protection programs to avoid assassination. Two of their colleagues have been murdered, bullets have been fired at their home, their children have been threatened, and local businessmen who want to use the land for cattle ranching have reportedly put a price on their heads.

On the other side of the country in São Paulo—Brazil’s biggest and richest city—Ana Mirtes woke up on election day ready to vote for former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. But she gave up when she realized her 10-year-old son would not eat that day if she spent the family’s money on a bus ride to the polling station. They are among the 33 million Brazilians who are hungry, many of whom had to choose between voting or eating. Under Bolsonaro, Brazil is back on the global Hunger Map.

These two stories may seem disparate, but they are connected by more than a struggle for survival.

São Paulo is the largest constituency in the country, giving its voters great influence in deciding the outcome of the elections, whose second and decisive round takes place on October 30. These elections in turn will affect the lives of forest defenders like Erasmo, hungry families like Mirtes’s, and the future of the Amazon rainforest. Which makes Brazil’s elections an international concern as well, because the Amazon plays a critical role in the fight to preserve a livable global climate.

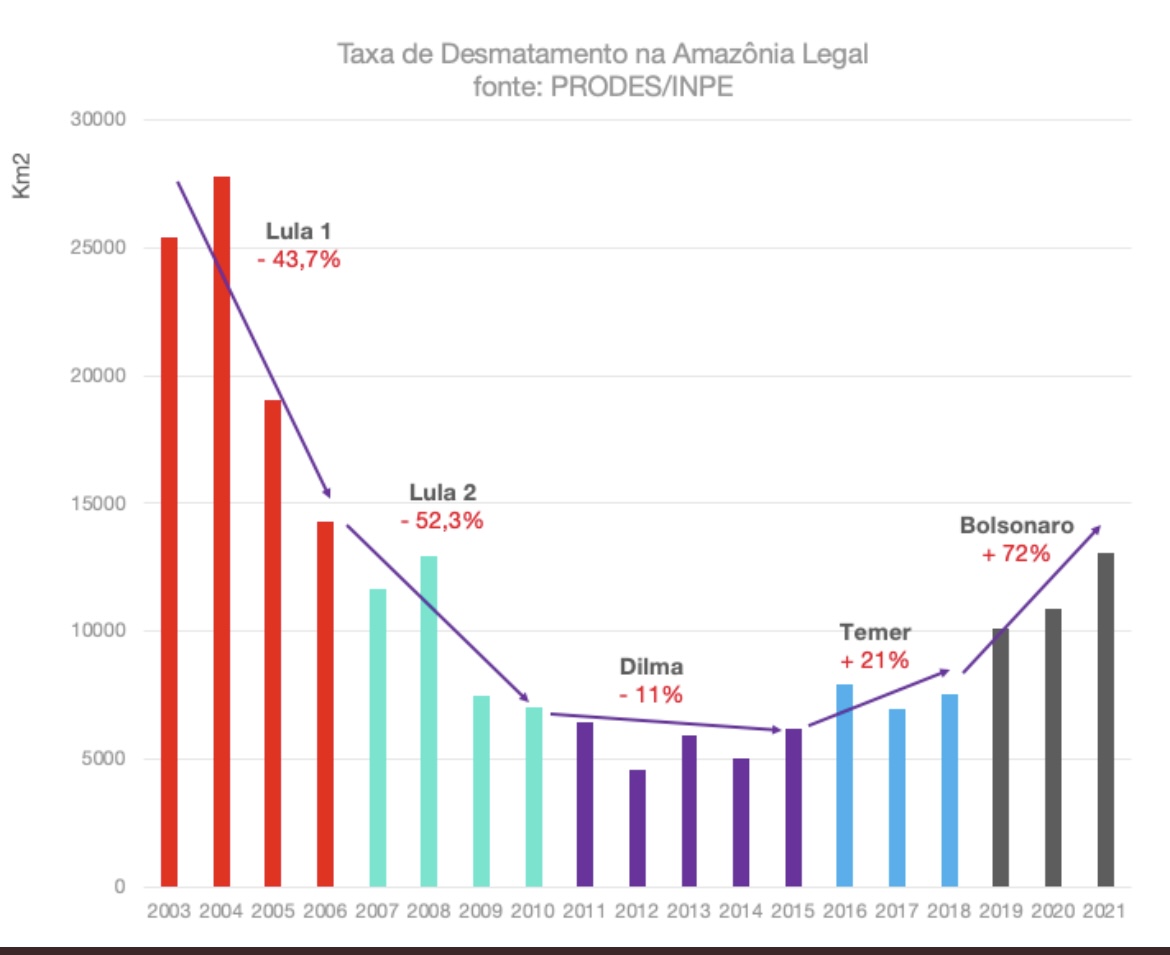

Under Bolsonaro, an ardent admirer of former President Donald Trump, deforestation of the world’s biggest rainforest has hit the highest rate in 15 years. On August 19, 2019, Ana Mirtes and the entire population of Sao Paulo saw “day turn to night” in the gigantic metropolis as a result of a cloud of ash from the fires in the Amazon. It was a sign that what happens in the forest has repercussions more than a thousand miles away.

This is also how the election in Brazil should be understood. The poll results here will not just shape national politics, but the health of the rainforest, which has a powerful knock-on effect on regional weather systems and the global climate. Without a healthy Amazon, whose trees absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, it will be extremely difficult to stop the planet from heating to a dangerous level. The signs are not encouraging. Recent scientific research has shown that parts of the forest already emit more carbon than they absorb, creating a climate foe from what used to be a climate friend. This, of course, is not the fault of the forest.

More than two billion trees have been cut down or burned in the Amazon under Bolsonaro’s watch, according to calculations by two of Brazil’s most prestigious forest research groups, Imazon and MapBiomass. That is 15 trees destroyed every second and with each one goes a far far greater population of other living beings, such as insects, termites, fungus, moss and lichen—that are vital for the healthy functioning of nature and the chemical composition of our atmosphere.

The power of nature is not measured by the number of individuals, but by their collective interaction. Everyone depends on everyone else. The whole is more vibrant and important than the sum of its parts. Thus, it is not trees that fall, but interconnected worlds. And each time, one of these tree-worlds is eradicated, the forest moves a little closer to a point of no return, when it can no longer regenerate and thus permanently degrades into a dry savannah.

Carlos Nobre, who is one of Brazil’s leading climate scientists, has warned that this tipping point is likely to be reached when the Amazon is between 20% and 25% cleared. Today, the level is estimated at between 17% and 20%. Four more years of Bolsonaro could be enough to push it over the edge.

The run-up to the election vividly highlighted this danger. September was the worst month for forest fires since 2010, as land grabbers and farmers rushed to take advantage of the permissive regulation under Bolsonaro before a possible change of power.

From my home in Altamira, the blazes could be seen across the river, and even when they were out of sight, the haze made the moon glow like an ember.

Read More: Why Is the Amazon Disappearing?

September also saw seven indigenous people murdered in different parts of Brazil, another horrendougly high toll that was in keeping with a central objective of this extreme-rightist government to remove obstacles to the exploitation of indigenous lands and nature reserves.

This is why the stakes are so high for the run-off on 30 October. Lula took 48.4% of the votes cast in the first round, falling a little short of an outright win. He goes into the run-off as favorite with a six million-vote lead over the incumbent. But polls suggest Bolsonaro is closing the gap and it will be a tough contest.

Forest leaders remember that Lula built large hydroelectric dams in the Amazon and his party profited from kick-backs from construction firms. But there is no comparison between this and the far deadlier threat posed by Bolsonaro, who deliberately delayed vaccinations against Covid-19 in Brazil and undermined measures to control the virus, leading to the death of 685,000 Brazilians. Among the many political forces from the left and right that have coalesced around Lula for the second round, this election is not just a contest of democracy versus authoritarianism; it is a choice between life and death.

The next Senate and Chamber of Deputies will have more of Bolsonaro’s supporters—and enemies of nature and Amazon conservation than ever before. The electorate’s priorities—and the power of Bolsonaro’s campaign machine—were apparent in the results of two candidates who symbolize the extremes of destruction and conservation. On one side was Ricardo Salles, Bolsonaro’s first environment minister who gutted forest protections and encouraged illegal logging and mining. On the other was Marina Silva, Lula’s first environment minister, who was primarily responsible for the fall in Amazon deforestation rates in the 90s and remains the most internationally renowned Brazilian environmentalist. Both were elected as federal deputies, but Salles had almost triple the votes of Silva.

In the Senate, which has restrained some of the most predatory bills in the last four years, Bolsonaro’s supporters made strong gains. Among the newcomers is Tereza Cristina, the right-wing president’s Minister of Agriculture, who is a champion of aggressively expanding agribusiness. During her tenure at the head of the ministry, she was nicknamed “the muse of poison” because her office approved more than 1,600 pesticides, some of them proven to be carcinogenic.

With both chambers of the legislature now packed with politicians in favor of no-holds-barred resource exploitation, environmentalists feel the only hope for saving the Amazon is a victory for Lula. And even then, it won’t be easy.

As resources grow scarcer and commodity prices rise, the war against nature in Brazil will grow fiercer in the coming years even if Lula wins. iIf Bolsonaro is re-elected, the world may well witness the end to the Amazon as we know it, with catastrophic global consequences, and dire implications for the Amazon’s defenders. As Erasmo’s wife Natalha put it. “If he wins, we will be annihilated.”

This article by Sumauma is published here as part of the global media collaboration Covering Climate Now.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com