Polls suggest Republicans may have a very good Election Day, possibly ending the night with control of both the House and Senate. If that happens, inflation is likely to be a major reason why, as months of rising prices have Americans stressed about the future. The cost of just about everything from food to energy to clothing is increasing—costs were up 6.2% in September from a year earlier, according to the Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation gauge, the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The reasons for these rising prices aren’t simple, but in advance of the 2022 midterm elections, politicians of all stripes are talking about inflation and placing the blame for it on their opponents. “Liberals spent trillions on a wasteful spending bill, and now we face record inflation,” the narrator says in an ad that the conservative American Action Network is running in contested House districts. “When corporations take advantage of a crisis, that’s price gouging, and it’s wrong,” Sen. Mark Kelly, a Democrat from Arizona, said in a campaign ad this summer.

Though some of these claims may explain part of why inflation is so high, none of them are the whole truth.

A bit of Econ 101 here: inflation is a supply-and-demand problem that happens when there is too much money chasing too few goods. But the reason for that phenomenon can be hard to pinpoint, and is usually due to the interplay of multiple factors.

Politicians have put forth lots of explanations for why, exactly, there is too much money chasing too few goods in the economy. Here, we fact check three of the most common claims heard on the campaign trail.

Claim #1: Inflation is Biden’s fault

Republicans like to argue that the spending bills shepherded through Congress by the Biden administration are the main reason there’s inflation. “This economy that Senator Masto has voted for—all of these Biden bills—has made our state absolutely unaffordable,” Nevada Senate candidate Adam Laxalt said in a recent town hall hosted by Sean Hannity.

This and other Republican claims about spending by Democrats generally refer to the American Rescue Plan, a $1.9 trillion pandemic relief bill passed in March 2021, and to the Inflation Reduction Act, passed in August 2022. Among other things, the American Rescue Plan sent up to $1,400 to people who qualified, expanded the child tax credit, and sent money to state and local governments. The Inflation Reduction Act levies some taxes on corporations and offers tax breaks to spur demand for clean energy; it also funds more IRS enforcement.

The biggest problem with arguing inflation is Biden’s fault because he gave too much money to consumers, of course, is that his predecessor also approved stimulus checks. In 2020, Congress passed and President Donald J. Trump signed the $2.2 trillion CARES Act and the $892 billion coronavirus aid package, both of which also sent stimulus checks to families.

Setting that aside, the series of stimulus bills Congress passed since the pandemic started in 2020 certainly put more money into the economy and likely did contribute some to inflation. But it would be a vast exaggeration to suggest that sending $1,400 checks to U.S. families could have led to the degree of inflation in the economy right now.

Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found that fiscal support measures in the U.S., including the bills passed in 2020, raised inflation by about 3 percentage points. But they also found that the stimulus checks caused U.S. disposable income to surge and then drop back down, and that those peaks came in mid-2020—when the first stimulus checks were sent out—and early 2021.

Some economists are even skeptical that the stimulus measures contributed as much as three percentage points to inflation. Research shows that most consumers saved the money they received from 2020 stimulus payments or used it to pay off debts.

And while U.S. inflation was previously running higher than inflation elsewhere, which might suggest that stimulus payments had a role, that’s no longer true. In September, inflation in the European Union was 10.9%, higher than that in the U.S., even though Europe did not issue stimulus checks to the degree that the U.S. did.

“This blaming Biden for inflation is just silly – inflation is a global phenomenon,” says Robert Kaufmann, a Boston University professor who studies energy and economics.

The simplest explanation for inflation, he says, is this: when COVID-19 began, businesses who were worried about the possibility of a long recession drastically cut production. Oil companies stopped searching for new drilling spots, factories canceled orders for parts, and consumer-facing businesses laid off workers.

But consumer spending barely slowed and companies couldn’t ramp up as quickly as needed. An energy company that stops drilling for oil can’t just restart by flipping a switch. And factories that source parts from around the world found getting orders filled took much longer, and that their suppliers had started working with other companies.

These factors alone would have created some inflation, but then Russia invaded Ukraine, a big supplier of wheat, and global oil markets panicked about the supply of crude oil because Russia is both a big supplier and a member of OPEC Plus. Crude oil is the main ingredient in diesel and gasoline and heating oil, so “that quickly translates to higher prices,” Kaufmann says. Energy costs grew 19.8% over the year ending in September.

Read more: Inflation is Going To Get Worse. Blame a Lack of Diesel

Of course, Kaufmann’s explanation covers why there were fewer goods in the economy; it doesn’t address why there was more money chasing them. But even if government spending did play a role in putting more money into the economy, economists say that impact was dwarfed by U.S. monetary policy, which Biden does not control. The Federal Reserve Board dropped interest rates to near zero at the beginning of the pandemic and did not begin raising them again until early 2022. That meant that everyone from consumers to companies were paying much less to borrow money, says Robert Taylor, a Stanford economist.

“The Fed got behind the curve,” says Taylor, who is known for coming up with the Taylor Rule in 1993, which basically argues that the Fed should raise interest rates by one-half percentage point for each percentage point that inflation has risen higher than the Fed’s target rate. For months, interest rates were too low when compared to inflation, he argues.

Fed policy is out of the hands of politicians in that the Fed is an independent agency, although its staff can be called to testify before Congress. “We are strongly committed to bringing inflation back down, and we are moving expeditiously to do so,” Fed Chair Jerome Powell testified to a Senate committee in June, just as the Fed was approving its highest interest rate hike since 1994.

Claim #2: Tax cuts will ease inflation

If there’s one thing that polls show, it’s that voters hate inflation. Which is why politicians trying to win in November are rushing to propose policies that will tackle inflation. A perennial favorite is proposing tax cuts. In Wisconsin, for example both Republican Sen. Ron Johnson and his Democratic opponent, Mandela Barnes, say they support tax cuts to fight inflation; while Republican Zach Nunn, a candidate for an Iowa House seat, wants to replicate the big income tax cuts his state passed this year in Washington. (Iowa is transitioning to a flat tax of 3.9%, which lowers tax rates for its highest earners).

As former UK Prime Minister Liz Truss learned very quickly during her recent 44 days in office, big tax cuts might be politically appealing but are a terrible idea in an economy suffering from high inflation. That’s because tax cuts put more money into the pockets of consumers and businesses, funneling more money into an economy that already has too much money chasing too few goods.

Read more: Liz Truss Has Resigned. Here’s How She Lost Control

“This idea of tax cuts to fight inflation is absurd,” says Benjamin R. Page, a senior fellow at the Tax Policy Center, a research group from the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution.

“It will exacerbate the problem.” What’s more, it’s hypocritical to argue that stimulus spending puts too much money into the economy, but that tax cuts do not, says Page. Tax cuts are essentially stimulus spending in a different format.

In the UK, for example, the Bank of England’s chief economist, Huw Pill, warned last month that the bank would have to make “significant” increases to interest rates to offset Truss’ proposed tax cuts because the tax cuts would “act as a stimulus to demand in the economy.”

In fact, politicians who are serious about combating inflation might do better to raise taxes, Page says. That would decrease the amount of money circulating in the economy, but obviously, it’s not an appealing prospect for politicians in an election year. “Inflation is very unpopular,” says Page, of the Tax Policy Center, “but almost any policy to fight inflation is also very unpopular.”

Claim #3: The main cause of inflation is corporate greed

This has become a big talking point for Democratic candidates as they have realized that their other messaging on inflation wasn’t working. Instead of avoiding the issue entirely, Democrats are blaming corporations for using inflation as a cover to increase their prices and earn more profits.

“It’s gross, and deeply unpatriotic, for the big corporations to be rolling around in cash while charging us record high prices for gas and groceries,” John Fetterman, the Democratic candidate for Pennsylvania’s U.S. Senate seat, wrote in an August opinion piece.

The argument also came up in a recent Congressional hearing in which Mike Konczal, the director of Macroeconomic Analysis at the Roosevelt Institute, presented research showing that 40% of price increases in the pandemic recovery were driven by corporate profit (excluding financial corporations), as opposed to higher wages. “We found that markups and profits skyrocketed in 2021 to their highest recorded level in the 1950s,” he said, adding that firms increased markups and profits in 2021 in the fastest annual pace since 1955.

But other economists argue that there is little evidence to suggest that companies could more easily raise prices in the last few years than they could have previously. After all, companies are always focused on delivering value to their shareholders, and will increase prices whenever they think the market allows it. But any company that increases its prices risks losing market share—and revenues—to a competitor who decides not to follow suit.

Not even Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen seems to buy into the corporate greed explanation. In June, when the New York Times’ Andrew Ross Sorkin asked her whether she agreed with comments made by others in the Biden administration that corporate greed was the reason for inflation, Yellen responded that “I see supply and demand as largely driving inflation.”

But even the economists who dispute the claim that inflation is the result of corporate greed say that it’s not unreasonable to suggest that it may be contributing a little bit to higher prices. “I’m not saying the simplistic “corporate greed is driving inflation” narrative is correct (it’s not), but it seems equally ideological to argue that corporate profits have no impact on inflation,” Luke Petach, an economics professor at Belmont University, wrote recently.

There’s no question that this year has been very good for the bottom lines of some companies in inflation-plagued industries. On Oct. 27, Shell said that it made $9.45 billion in the third quarter, its second-highest profit on record. The profits of both Exxon and Chevron hit records earlier this year. The cost of food has also contributed significantly to inflation, growing 11.2% over the year, and companies including Tyson Foods posted record profits in the beginning of the year.

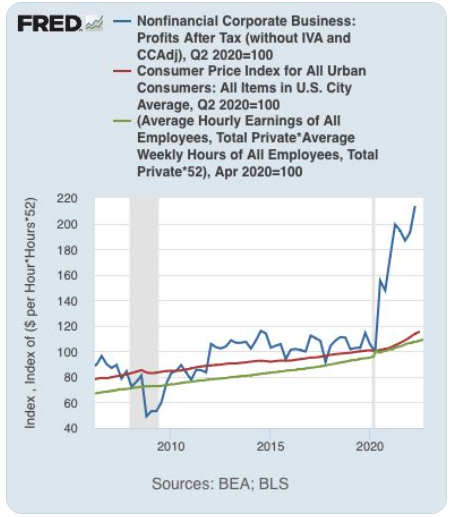

Petach made a chart comparing workers’ earnings, prices, and corporate profits, indexing them all to April 2020. The results are striking, showing corporate profits have more than doubled since 2020, while earnings and prices rose less than 20%.

“When corporate profits are at an all-time high,” he says, “It seems ridiculous to say that it’s having no effect.”

Corporations have more ability to increase prices if they don’t have many competitors, or if they already control so much of the market that most consumers have little choice but to pay higher prices. That’s why some Democrats argue that a decline of competition in the economy could be allowing corporations to hike prices. Even Treasury Secretary Yellen, who seemed skeptical about the claim that corporate greed was driving inflation, followed her answer in June by adding that research suggests many segments of the U.S. economy have less competition than in the past. Research by Konczal, of the Roosevelt Institute, found that companies with more market power were more likely to increase prices before the pandemic—and that they used the pandemic to hike prices even more than they had previously.

Of course, there aren’t a whole lot of easy policy solutions to restricting corporate markups in a free market economy. Though the Biden administration has appointed big names in antitrust enforcement to government positions, it has yet to advance any meaningful policy on the issue.

Besides, in the 1970s, price controls set by the Nixon administration to combat inflation ended in severe shortages and angry consumers. Then and now, politicians eventually came to realize that there’s not much they can do about inflation. Except, of course, for pointing fingers.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com