Donald Trump read the names off a teleprompter. It was July 2021, and the former President was speaking at the conservative advocacy group Turning Point Action’s confab in Phoenix, where candidates vying for the GOP nomination for Arizona governor hoped to grab his attention. Insiders expected Trump to endorse Matt Salmon, a former congressman with whom he was known to golf.

Trump took a moment to recognize the candidates who had shown up. First was Salmon, who drew tepid applause. Then he mentioned Kari Lake. Thousands of fans rose to their feet and began chanting her name. Trump was visibly shocked. “Whoa!” he said, searching for Lake in the audience. “This could be a big night for you.”

After Trump finished his speech, he approached one of his confidants backstage with a question: Who is Kari Lake?

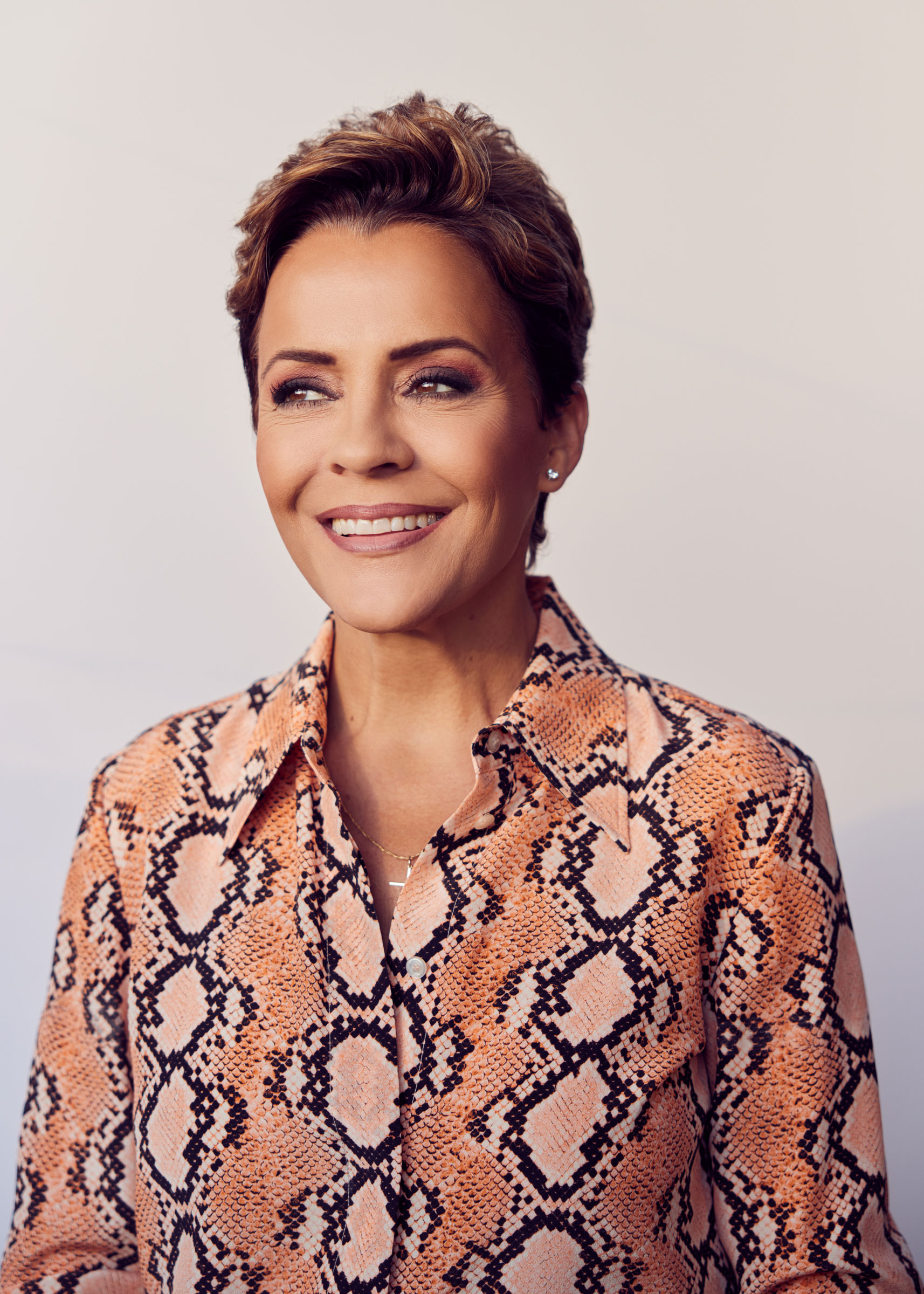

An anchor for Fox 10 Phoenix until last year, Lake has been a fixture in Arizona homes for more than a quarter of a century. Since then, she’s parlayed what may matter most in today’s Republican Party—the ability to captivate an audience—into a startling political ascent. Polls show her locked in a dead heat with Democrat Katie Hobbs in the race to lead a key battleground state. The prospect of a Lake victory electrifies the right and terrifies the left.

If elected, Lake, 53, would oversee Arizona’s next election—a source of profound anxiety for Democrats and some Republicans, who worry that Lake would subvert the will of the voters in 2024. Lake has said Joe Biden “lost the election and shouldn’t be in the White House,” and claimed that she wouldn’t have certified Biden’s Arizona victory in 2020. Liz Cheney, the Republican vice chair of the House panel investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, is among those who have cast Lake as a threat to American democracy.

“That’s total bull—t,” Lake told me when I raised these concerns with her. “I will certify the 2024 election. You know why? Because we’re going to have election integrity bills that are passed that shore up our election laws, that remove loopholes from cheating. By the 2024 election, we’re going to have honest elections in Arizona, full stop.”

Such a declaration is unlikely to appease her detractors, who fear that her definition of “honest elections” will only be ones that Republicans win.

Lake’s mark on the state as governor wouldn’t stop there. She would have a major say over the future of abortion access in Arizona. She has vowed to root out “woke teaching” from schools and block vaccine mandates of any kind, measures that Arizona political analysts suspect would be supported in the state legislature. And she’s planning to engage the Biden administration in a series of legal fights—on everything from education to the border—with the goal of engineering favorable rulings from a conservative Supreme Court.

Yet even if Lake suffers a narrow loss, her growing profile and connection with crowds suggests she’ll remain a force within the GOP. Pundits are already speculating that Trump could tap her as a running mate in 2024. In other words, she could be the future of the Republican Party.

It’s easy to see why when Lake takes the stage at a chic Scottsdale sports bar in mid-October. Although she regularly draws huge crowds, Lake still acts surprised over how many people show up to see her. “Are they offering two-for-one drinks, or what?” she says to the hundreds packed shoulder-to-shoulder.

It never takes long for Lake to take aim at her favorite target. “Raise your hand if you’re with the fake news,” she says, to big belly laughs. “They don’t want to ask about inflation. They don’t want to ask about security at the border. They don’t want to ask about crime. They don’t want to ask about the struggles families are facing.”

For the next 55 minutes, Lake—garbed in a shiny pink blouse, her hair styled in a perfect pixie cut, a gold cross hanging below her neck—dazzles the crowd with personal asides, punchlines, and provocations. She whips them up by deriding schools for incorporating trans issues into the curriculum. And she paints her entry into politics as part of a last stand to save America from irreversible decline. “I walked away from my paycheck, which was beautiful and large, because I realized what good is a paycheck, what good is all of that, if you don’t have a country to enjoy it in? If our children, if our babies, aren’t free?”

It was a vivid exhibition of Lake’s knack for retail politics and the credibility she has with the GOP base that comes from rebelling against the “fake news” from within.

Paul and Jenna Wyer, a couple in their 40s from Scottsdale, hung on to Lake’s every word. They disagree with her on perhaps the most divisive social issue—they support abortion rights, she does not—but they don’t see that as a dealbreaker. “We watched her on TV,” Jenna tells me. “A lot of her values are at the core of our own values as a family.”

Republican Steve May, a former member of the Arizona House, has a piercing memory of Lake. In 1999, May defied the military’s “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” policy. When he sat down with Lake for an interview, she asked how he was handling the attention. He said he found it unsettling that “people would come up to me at the grocery store, the airport, and just start a conversation as if they knew me and we had a prior relationship.”

“Steve, they do have a relationship with you,” Lake told him, according to May. “You have been in their living room. You just don’t have a relationship with them.”

It’s a moment that May believes provides insight into Lake’s campaign. “That’s the belief and experience that she hopes will elect her governor: familiarity,” he says. “She knows this is her superpower.”

Lake was born in Rock Island, Illinois in 1969, but grew up in eastern Iowa. She was the youngest of nine children, with eight sisters and one brother. When she was seven years old, her parents divorced and had a custody battle. Her father won, which Lake attributes to the fact that he had a more stable job situation.

Larry Lake was a high school teacher and football coach. He often brought his young daughter with him to practices. Because they lived in a rural school district, Lake went to the same school where her father taught, North Scott Senior High in Eldridge, Iowa. She ended up taking one of his social studies classes. She got a B.

Her mother, Sheila Lake, was a nurse. While Lake describes her as an “amazing human,” she says she’s glad her father raised her. “Obviously, a mother’s really important in those first few years of a child’s life, in that nurturing phase, and then after that, I believe fathers are actually almost more important.” She describes women who grew up without fathers as often “searching for somebody to define them,” but that “when you have a strong father in your life as a girl, you don’t need somebody else to define you. Your father helped define you.”

At 16, Lake graduated from high school early after amassing enough credits, and enrolled at the University of Iowa. During her first two years, she thought she would become an elementary school teacher, but she had no major, and worked various part-time jobs to pay her tuition, including at a pizza joint and a computer store. She was also, at one point, a janitor at a drug treatment center. After her sophomore year, she took two years off of school, working at first as a radio sales agent, and later as a receptionist, while she lived with an older sister and her sister’s husband in Minneapolis.

Her brother-in-law watched the local news every night, something Lake had never done much of before. She was transfixed. “I started watching it, and I’m like, this looks like a great job,” she says. “You’re in the middle of everything.”

She returned to Iowa City a year later and became a communications major, with the goal of getting into broadcasting. “When I went back, I was on a mission, and I had a passion, and I knew exactly what I wanted to do,” she says.

After graduating in 1992, she worked as a production assistant at KWQC, in Davenport, Iowa, before joining another station in Rock Island for two years. After that, NBC’s Channel 12 in Phoenix hired her as a weekend weather anchor.

Lake worked at NBC for four years, until she left for a one-year stint in Albany, New York. In 1999, she returned to Phoenix as Fox 10’s evening anchor, taking the lead role at 5 and 9 p.m. Lake and her co-host John Hook soon became one of the the most watched local news programs in Arizona’s largest market, working side by side for 22 years.

For most of Lake’s time in the newsroom, she wasn’t known to be outspoken about politics, which made her decision to run for office all the more surprising to her former colleagues. “It was such a shock to me,” says Diana Pike, Lake’s HR manager for nearly two decades.

Lake says she registered as a Republican the day she turned 18 but kept her views out of her work. “If you’re a good journalist,” she says, “you don’t push your opinion.”

She says she grew embittered with her party during the George W. Bush Administration, and donated to John Kerry’s campaign in 2004 and Barack Obama’s in 2008, both in protest of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, and registered as a Democrat for a four-year-stretch. “I was thinking which of these candidates is going to end the war,” she explains. “I’d covered John McCain for 20 years, and I didn’t think it was going to be him. So I took a shot on our first Black president.”

According to Lake, Trump’s message first resonated with her when he delivered his campaign launch speech in June of 2015. “The media went crazy,” Lake says. “I went, wait a minute, why are they going crazy? He’s actually speaking the language of a lot of American people.”

There were few outward signs at the time of Lake’s conversion to MAGA faithful. In 2016, she floated what she called a “humane and fair” proposal on social media that would give amnesty to millions of immigrants who came to the U.S. illegally. (Her campaign says she was only asking her followers their thoughts on the idea, not endorsing it.)

But Lake’s social media posts would start to demonstrate a right-ward shift in the years ahead. In April 2018, she faced a backlash for tweeting that the pro-public education movement “Red for Ed” was conspiring to legalize marijuana. Lake later apologized on air.

Several of Lake’s Fox colleagues say they first noticed a change in her thinking after she returned from a June 2019 trip to Washington to interview Stephanie Grisham, an Arizona native who was serving as Melania Trump’s communications director. While there, she also scored an interview with the President.

“She was more pro-Trump when she came back from that assignment,” says a former colleague, who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss Lake with reporters.

From then on, Lake’s former colleagues say, she began challenging the producers over their political coverage, pressing them over what she argued was their covering one side of the story, or ignoring Trump’s side. “Oftentimes, those things would be some ridiculous conspiracy theories and things like that,” one of them adds.

In July 2019, she faced scrutiny for joining Parler, a social media platform known for its right-wing audience. “Sounds like this is the only social media site that is actually putting the First Amendment first,” she wrote on her first post. “Bravo!” Later that month, she was caught on a hot mic dismissing the controversy and the potential for blowback from a local weekly newspaper, the Phoenix New Times. “F–k them,” she said. “That’s a rag for selling marijuana.”

But Lake’s disillusionment with journalism peaked during the pandemic. She was isolated at home with her family. Fox 10 was limiting the number of people allowed into the office. Her husband, Jeff Halperin, a videographer who used to work at NBC’s Phoenix affiliate, set up a studio in their house, with a sophisticated lighting display and a state-of-the-art camera. Lake’s co-anchor, Hook, worked from the newsroom.

Even though more than 1 million Americans have died from the virus, Lake believes the wall-to-wall Covid coverage early in the pandemic was tantamount to fear mongering. “I don’t know how anybody is still a journalist after coming through Covid, to be honest,” she says. “You couldn’t question anything about Covid. That’s where I had a problem. I just felt like, wow, this has ceased being journalism. It is pure propaganda.”

In one instance, Lake wanted to do a segment on a patient who recovered from Covid after taking ivermectin, a drug mostly used to treat animals that Trump and other right-wing media figures had promoted as a possible treatment but whose efficacy had not been established. The station killed the story, according to both her best friend Lisa Dale and her sister Jill Stringham. (Fox 10 Phoenix declined to comment for this report.)

Stringham recalls Lake saying, “I can’t do this anymore. It’s killing me inside. It’s eating away my soul.”

Lake had been raised Catholic. She and Jeff—whose mother was Colombian and father was Jewish—raised their kids in the faith, but were put off by the Church’s child abuse scandals. “So we just kind of raised them Christian and believed in God and Jesus and all that, but we weren’t overly active in the church,” Lake says.

That changed during the pandemic when Dale introduced her to a nearby Evangelical church. “Our Catholic Church was closed,” Lake says with frustration evident in her voice. “It was by appointment only. And we really felt that we needed to be in church. We were struggling as a people.” Lake recalls stepping through the doors of Scottsdale Bible Church for the first time and feeling a jolt to her system. “It was like an epiphany for me that I had never experienced before in my faith journey.”

By December of 2020, Lake had reached a breaking point. She told Dale she was planning to leave Fox 10.

“You can’t quit,” Dale told her, ticking off all the objections: “How much time do you have left on your contract? How much money have you saved? Are you going to have to live in my house?” According to Dale, Lake said, “I can’t look at myself in the mirror while I’m putting on my makeup and feel proud about what I do anymore.”

The next day, Dale and Lake went to church, and the pastor delivered a sermon that might as well have been speaking directly to Lake.

“What you do for work is important,” he told his flock, per Dale’s recollection, “but it shouldn’t control or change who you are. God doesn’t want his children to be miserable in a dead-end job that doesn’t make them happy.”

When they got in the car afterwards, Dale turned to Lake. “Kari, you need to quit.” Lake’s eyes pierced hers. “I know,” she said.

In March of 2021, Lake resigned by posting on social media a two-and-a-half minute video that her husband filmed of her, shot in soft focus and with a gauzy tone. “In the last few years, I haven’t felt proud to be a member of the media,” Lake says in the clip. By the next morning, it went viral, and calls for her to run for office soon followed, from users on social media, people on the street, and GOP operatives.

Lake had already begun to weigh jobs in the private sector, including as a media consultant or as a virtual reality specialist. She also had offers to join conservative media outlets, she says. But now she began to consider politics. So she contacted some Arizona politicos for their advice, such as Sal Diccicio, a Phoenix city council member, and Kelli Ward, the chairwoman of the Arizona Republican Party. “What’s the first step?” Lake recalls asking them.

Meanwhile, she began to surround herself with other political vets, like Tom Van Flein, a former chief of staff for Rep. Paul Gosar who was part of Sarah Palin’s inner circle when she was running for vice president, and Sam Stone, who was Diccicio’s chief of staff.

“I was kind of contemplating running for the U.S. Senate or running for governor,” she says, but she chose the latter because she didn’t want to leave Arizona. She also had little interest in being one vote in a larger body. She wanted executive authority.

“I realized during Covid—I think the whole country realized—just how powerful our governors are,” she says. “They had the power to do right, or they could really mess our lives up. Unfortunately, too many of them messed our lives up and shut our schools down, masked our children, closed our businesses, shut our churches down, quarantined healthy people. It was coming from governors.”

In May of 2021, Lake drove two hours north to Pine, Arizona, to celebrate Stringham’s birthday. Midway through dinner, Lake told her sister that she figured out what she was going to do next—run for office. Stringham recalls asking her which office, assuming she would say either state senator or representative.

“She goes ‘Governor,’” Stringham recalls. “I think I might have dropped my fork.”

When the Lake campaign launched in June of 2021, local pundits brushed her off. She may have been well known throughout the state—“I probably had $10 million in name ID or more,” Lake says—but she had nowhere near the war chest of her opponents. And she was a first-time candidate.

Her bid for the GOP nomination shifted from longshot to frontrunner status on July 24, 2021, when Turning Point Action held its Phoenix summit with Trump. Once the former president stepped off the stage, he asked Charlie Kirk, Turning Point’s founder, about the woman who had roused the crowd. “I want to meet with her,” he said, according to Kirk. “What is her story?”

It was exactly the kind of reception that Trump looks for in a candidate. “When President Trump saw how popular she was with the grassroots here in Arizona, arguably one of the most important target states, it was like, how do you deny that?” says Tyler Bowyer, Turning Point Action’s chief operating officer, who helped plan the rally.

Read more: Why Donald Trump Is Making Extremely Local Endorsements

Trump invited Lake and her husband to Trump Tower the next month. At the outset of the conversation, Trump brought up the reaction to her in Phoenix. “That’s not a poll that you hire some pollster to do,” Trump told her, according to Lake. “That’s a real poll. That’s the people telling you who they like.”

The meeting was supposed to last only 20 minutes. It went on for over an hour. By the end, Trump told Lake he was going to support her. It happened to be Lake’s birthday.

Trump blasted out his seal of approval in a statement a month later, far earlier than he had gotten involved in other races in the midterm election cycle. “Few can take on the Fake News Media like Kari,” Trump said. “She has my Complete and Total endorsement.”

Everywhere Lake goes, she has a lavalier mic attached to her. It’s for her husband, who films practically her every move, to capture each conversation she has with journalists. They say it’s a form of self-protection. If Lake thinks a reporter has misrepresented her words, or ambushed her with a loaded question, her team will post the tete-a-tete online. The strategy has helped establish her as one of the MAGA right’s rising stars.

“I’m not afraid of the media because I’ve worked in the media,” she tells me. “I don’t understand why people are afraid of the media. Half of these people—they’re not very smart. I hate to say it. I mean, there are smart people in the media, but the majority of them aren’t very smart. So it’s not hard to outsmart them. I think people running for office should just remember that.”

Lake has shown herself adept at manufacturing feisty clashes with reporters.

A few weeks before the primary, her husband filmed a CNN reporter approaching Lake outside an event, asking if she had a moment to chat. “I’ll do an interview,” Lake says, “but only if you agree to air it on CNN+,” referring to the recently defunct steaming service. “Does that still exist? I didn’t think so, because the people don’t like what you guys are peddling, which is propaganda.”

Lake’s team posted the clip on social media and, within hours, it caught on like wildfire, eventually capturing the attention of Tucker Carlson, who lionized the exchange as offering a blueprint for how Republican politicians should deal with the mainstream press.

In August, Lake won her primary by five percentage points, carrying every single county in the state. That set up a clash with Hobbs, who, in the face of pressure from Trump and his allies, helped to certify Biden’s narrow 2020 win as Arizona’s secretary of state, with Republican Gov. Doug Ducey and a GOP-controlled legislature.

Democrats fear that Hobbs has run a lackluster campaign, marked by her refusal to debate Lake, her absence on the trail, and a past employee suing her over discrimination. News of a registration error in her office this month that could affect up to 6,000 voters added to a perception of a flailing bid.

A stronger candidate could counter Lake more effectively, argue Democratic operatives, who say their focus groups show Lake’s message shouldn’t be resonating with Arizona’s middle-of-the-road voters. “The more people learn about Kari Lake, the more hesitant they are,” says Eric Hyers, a Democratic strategist who has managed multiple gubernatorial campaigns. “You have bomb throwers like Kari Lake win congressional offices all the time, but it’s much tougher for someone who thrives on chaos and who thrives on controversy to get elected governor.”

Hobbs declined multiple requests for an interview, and would only agree to respond to written questions. “Kari Lake is only interested in creating a spectacle,” she wrote to TIME, adding, “Our race for governor isn’t about Democrats vs. Republicans. It’s about sanity vs. chaos.”

The issues that divide them are stark. Since the Supreme Court ended federal abortion rights in June, Arizona has been mired in a legal battle over which state law is now in effect: a total ban on the procedure from 1864, or a 15-week ban that Gov. Ducey signed this year. For now, the latter is being enforced. Hobbs has called for restoring Roe v. Wade. She also wants to allow abortions during the third trimester under extraordinary circumstances. Lake, in contrast, has called abortion “the ultimate sin” and, in recent weeks, has been noncommittal on whether she would back a total ban or a 15-week ban when in office. “I’m going to be governor, not emperor,” she says. “I will execute the laws on the books.”

Hobbs has also insisted that Lake would refuse to certify the presidential election in two years if a Democrat won Arizona. “As Donald Trump’s most loyal foot soldier in denying the results of the 2020 election, Kari Lake cannot be in a position of power to certify the 2024 election,” Hobbs says.

It’s a concern shared also among some Arizona Republicans, including Rusty Bowers, the state’s longtime GOP Speaker of the House who stood up against Trump and Rudy Giuliani’s push to have him hold a special session to decertify Biden’s win there. Since then, Bowers has lost a campaign for the state senate.

Bowers says it would be hard for a governor to decertify an election result on their own without both a like-minded secretary of state and an acquiescent legislature. Mark Finchem, the GOP nominee for secretary of state, has also denied that Biden won the election and is currently polling ahead of Democrat Adrian Fontes. Such a trifecta, Bowers posits, could be “a perfect storm depending on who gets the speakership.”

Read more: Conspiracy Theorists Want to Run America’s Elections. These Are the Candidates Standing in Their Way

Lake insists such fears are unfounded, and yet she hasn’t said explicitly that she would certify the election no matter who wins. She says she will work with the legislature to pass an election integrity bill that improves the state’s elections system to the point that she would have no reason not to certify the results in 2024. Arizona was ground zero for 2020 election disputes, and despite a litany of allegations, no evidence of substantial fraud has come to light. A comprehensive investigation by Arizona’s Maricopa County found “100 potentially questionable ballots cast out of 2.1 million.”

Lake and her top aides say they want to harden the state’s voter ID requirements and transition fully to paper ballots. To avoid the possibility of hacking, they say they want to use electronic machines that don’t rely on software to tabulate the votes. And lastly, they want to mandate an annual audit of all elections.

Of course, the devil is always in the details—and those haven’t been fleshed out yet, Lake admits. “I don’t know exactly what it’s going to look like,” she tells me, referring to the elections overhaul she envisions. “But I will guarantee you this: We will have honest elections. That is a top priority.”

Other top priorities include issuing a “Declaration of Invasion” at the southern border, which Lake and her team say would pave the way for Arizona to complete Trump’s border wall in the state, and station Arizona’s national guard troops along the border. Both of those efforts would likely set up legal fights with the federal government and outside groups, which Lake’s team predicts would eventually make it to the Supreme Court. “I hope it does,” Lake says.

The calculated attempt to bring about court battles with the Biden administration may sound like a platform for rabble rousing. It is that, but it’s not only that. Lake’s team is betting that an emboldened six-vote conservative Supreme Court majority will welcome the opportunity to rewrite constitutional law in order to bless aggressive, boundary-pushing conservative policymaking.

A Lake victory would be a jarring setback for Democrats in a state that was one of their biggest triumphs two years ago. Arizona is a battleground for the soul of America. It’s poised on a knife’s edge: an increasingly diverse electorate that just barely went blue in 2020 but that is now fielding hardcore conservatives who stand a good chance of winning.

But even before the votes have been cast, Lake has established herself as a MAGA elite. GOP hopefuls are expected to start seeking her endorsement almost as aggressively as Trump’s, according to Republican insiders.

It’s not the only way that expectations are high. Toward the end of the event in Scottsdale, the moderator gets to a question surely on everyone’s minds: “Are you going to run for President?”

Lake’s answer is at once conventional and unorthodox. She says she’s focused on her current race. But she conveys the message in what has become her trademark manner—by bashing her former colleagues in the press.

“It’s so funny that this question is even being asked,” she says, “because the fake news, when I first got into this, they were calling me incompetent and ‘She doesn’t know what she’s doing.’ Now they’re like, ‘Are you going to run for VP? Are you going to be President?’ It’s like, okay, slow down, everybody.”

The audience is eating it all up. But then, Lake’s tone and body language harden. She points toward the back of the room, her finger aimed at the cameras and the reporters jotting down her every word. “I want to let the fake news know: No, I am not. I’m going to be the governor,” she says. “I’m going to be your worst nightmare for eight years.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com