This article is part of The D.C. Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

It has to be said from the start and repeatedly: political violence is never acceptable. It also must be said that leveraging an accusation that such violence has transpired should not be done lightly. Getting it wrong is a huge, huge risk.

Which takes us to the South Florida city of Hialeah, where someone attacked a man allegedly wearing a campaign T-shirt for Republican Sen. Marco Rubio and donning a hat promoting Gov. Ron DeSantis. The police report describes a confrontation between the 27-year-old victim and at least one other person. An arrest for aggravated battery and causing great bodily harm, a second-degree felony, has been made.

But here’s where things might get dicey: Rubio is alleging the attack was for the victim’s political beliefs.

Rubio first made the assertion on Twitter midday Monday, posting photographs of a bloodied individual in a Rubio shirt on a stretcher, in an ambulance, and in the hospital. The conservative echo chamber picked it up, snowballing into Fox News’ scripts within hours.

“Last night one of our canvassers wearing my T-shirt and a Desantis hat was brutally attacked by 4 animals who told him Republicans weren’t allowed in their neighborhood in #Hialeah #Florida,” Rubio tweeted. “He suffered internal bleeding, a broken jaw & will need facial reconstructive surgery.”

It didn’t take long for Twitter users to identify the victim as Christopher Monzon, an activist who might not exactly be Gen Z’s Rosa Parks. The self-described “Cuban Confederate” was a member of the League of the South, a group the Southern Poverty Law Center has called a white supremacist group. He is also a failed city council candidate who joined the protesters at 2017’s deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Va.. He pleaded no contest to aggravated assault and served probation for allegedly using a flagpole flying a Confederate flag weeks after Charlottesville to attack people who were demonstrating in support of removing Confederate leaders’ names from streets in Hollywood, Fla. The Miami-Dade Republican Committee on Monday confirmed the attack victim was one of its former executive committee members. So did the Miami Springs Republican Club.

Monzon told The New York Times for a June story that he was on a “path to de-radicalization.”

Still, members of the Vice City Proud Boys were reportedly standing guard at the hospital on Monday against reporters who wanted to talk with him. The group has effectively taken over the Miami-Dade GOP.

Again, political violence of any stripe is never acceptable. But within hours, Rubio seemed to start walking it back, perhaps realizing this might not be the story of a doe-eyed idealist innocently passing out campaign fliers. Monzon was attacked in a Miami suburb that is largely Cuban American, conservative, and working class. (Credit to my Miami-based buddy Marc Caputo, who is among the best political writers in the state, for his reporting on Monday on the locale, which added context about the attack.)

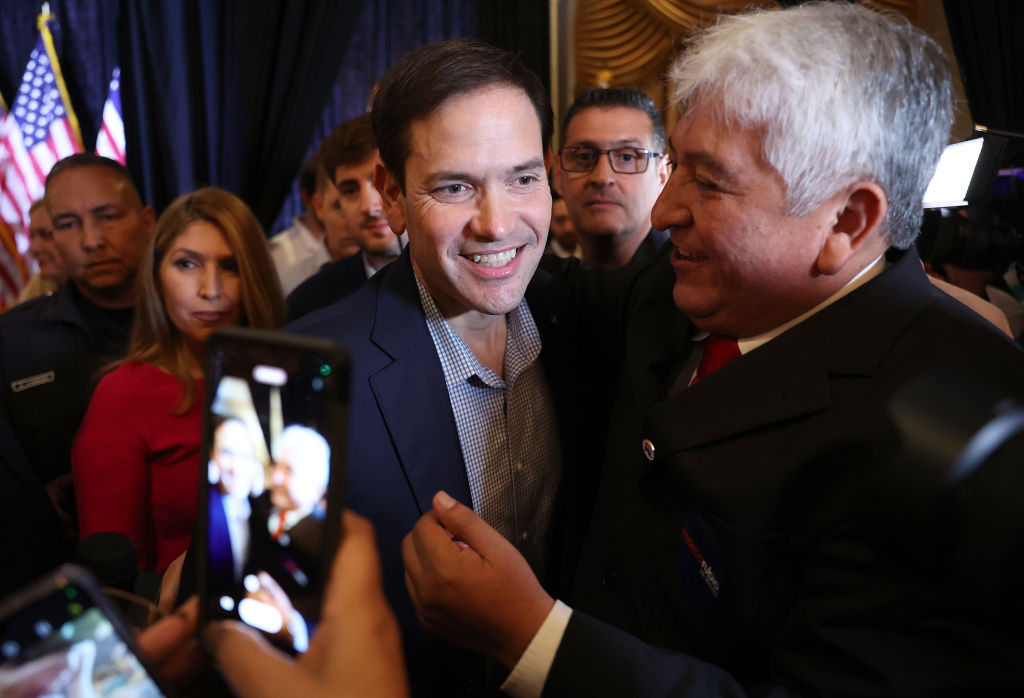

“Sadly, we got the news and we’re still waiting for details. It’s always important to have details,” Rubio said Monday at an event promoting the opening of the early-vote window in Florida. “We’re not like these other people that always jump to conclusions, but we know this: Someone wearing a Rubio T-shirt and a DeSantis hat was walking in a neighborhood not far from here yesterday when four individuals assaulted him, broke his nose, broke his jaw.”

Rubio, locked in one of the handful of Senate races that will determine the balance of power in Washington come January, has stumbled into what might well be his October Surprise. A Hialeah Police Department sergeant who serves as its spokesman said his colleagues would “allow the investigation to reveal that” politics came into play, but there was “no indication that is the case” as yet. The police report mentions just two others involved—not four as Rubio stated—and includes no mention of political motivation. Instead, it says one of the two other parties actually was attacking suspect Javier Lopez—not Monzon.

Read more: In Florida Senate Race, GOP Messaging on Crime Runs Up Against an Ex-Cop Opponent

Monzon absolutely has no obligation to tell his story to the public. But after initially agreeing to interviews, he canceled them. His phone is going to voicemail. Perfectly fine, but it raises some red flags. Rubio’s allies are quietly telling reporters that Monzon was actually working for the Republican Party of Florida, not the campaign proper; it’s a distinction that may matter in courtrooms.

Zooming out, the fact an operative of either party might have been targeted for violence is hardly surprising. Since the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, pollsters have been trying to gauge Americans’ appetite for such conduct. A full two-thirds of Americans expect political violence to increase, according to a recent CBS News poll, up from half in January of last year. Half of Americans from both parties see the other side as an enemy in that same poll. One-in-five Americans actually condone political violence, according to another poll. In other words, this may be our new normal, and that’s not OK in a democracy.

So, giving Rubio the benefit of good-faith that he wasn’t a political craven when he made his statements, he was, however, an extrapolator—if not a gambler. And when a candidate gets over their skis on such allegations, it can become a drag on their campaign. Just ask the staff of Sen. John McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign, which amplified reports of an alleged attack from a Barack Obama supporter; the McCain volunteer later admitted the event was a hoax and got criminal probation.

Again, political violence is indisputably wrong. But so, too, is trying to leverage it as a leg up. Rubio is leading in the polls, although his challenger, Rep. Val Demings, is proving more difficult to vanquish than D.C. expected over the summer. The former Orlando police chief has been a fundraising juggernaut and skilled debater. To have veered into this storyline may be risky for Rubio, especially given independents aren’t exactly sympathetic to Monzon’s strain of conservatism.

Rubio may now find himself spending the next two weeks trying to explain why the Proud Boys were guarding the room of a canvasser who previously used a Confederate flag as a weapon and marched with slavery-enabling apologists—in a campaign against a candidate who may become just the third Black woman elected to the chamber in history. It was a tweet Rubio probably hoped would goose his side. But he now owns it.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the D.C. Brief newsletter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com