In a region where at least 15 nations criminalize homosexuality and in those that don’t, there’s a “don’t ask, don’t tell culture,” queer Arab communities may have been forced into the shadows but they undeniably exist.

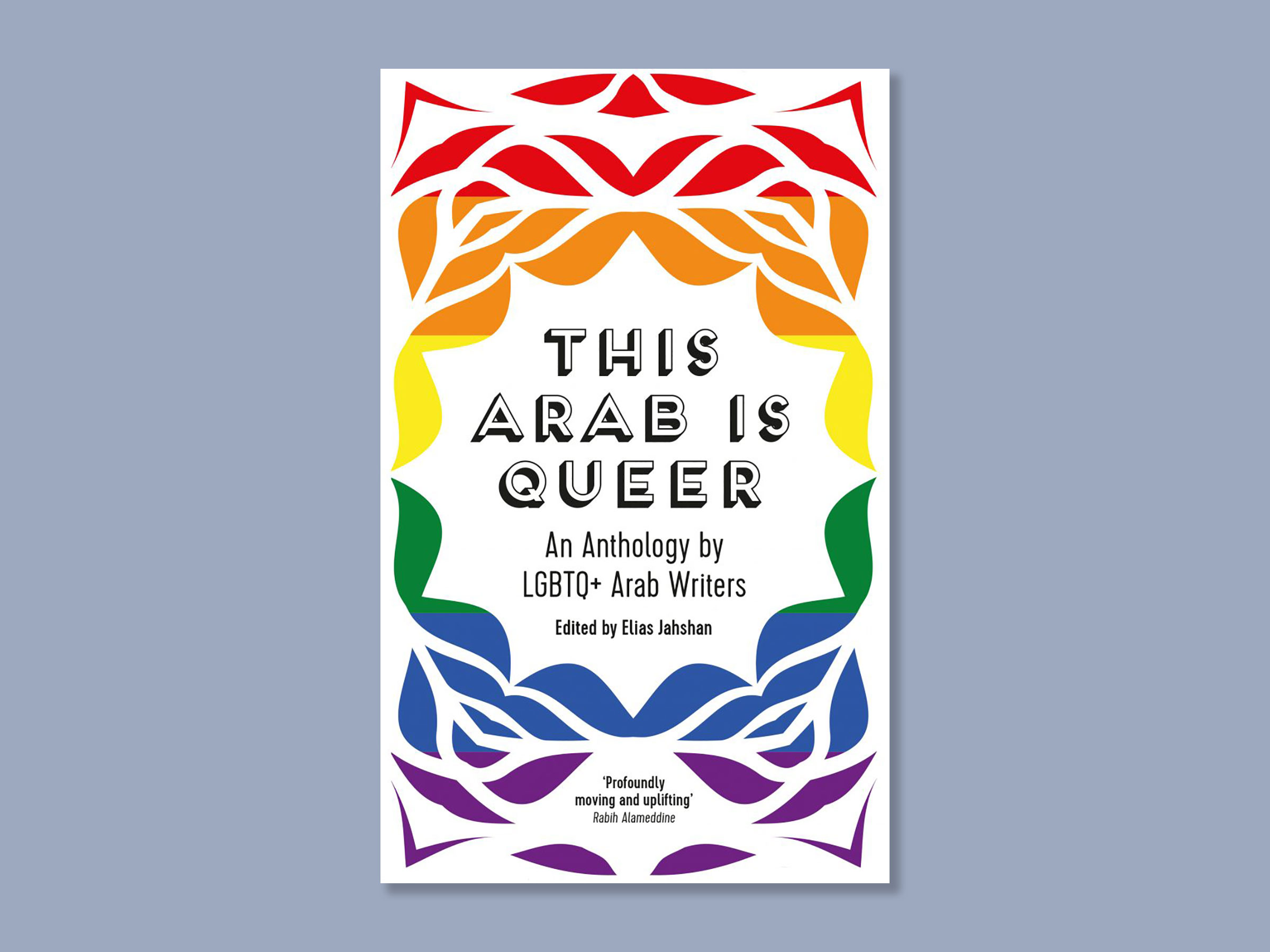

That’s why Tuesday’s U.S. debut of This Arab is Queer, a new anthology edited by Elias Jahshan, an Australian journalist of Palestinian and Lebanese descent living in London, is so groundbreaking. Jahshan asked 18 writers who were born or raised in the Arab region or who are from the diaspora to ruminate on this intersection of their identity.

“I wanted to show that we have agency and can tell our stories in our own way. We don’t need people speaking over us all the time,” says Jahshan.

His decision to platform queer Arab experiences was sparked after his time as Editor of the Star Observer—Australia’s longest-running LGBTQ+ media outlet—from 2013 to 2016. During his tenure, Jahshan says the Western media landscape was dominated by atrocities committed by Islamic State across Iraq and Syria.

Jahshan, who was raised in a Christian household, says he found “a lot of underlying Islamophobia and racism” in the reporting of how those perceived to be gay were hurled from rooftops and stoned for engaging in what the extremist group referred to as “sexual deviance.” Not only did the reports lack nuance, Jahshan says, but the gruesome killings were weaponized as an inaccurate stereotype of the queer Arab experience. “Whenever I tell people I’m gay and I support free Palestine, instantly I’m told why don’t you try being gay [there] and see if Hamas throw you off a rooftop,” says Jahshan.

In 2019, he reached out to contributors in the region and across the diaspora to help him set the record straight.

Below, TIME speaks to some of these brave contributors.

Khalid Abdel-Hadi

In his essay, “My Kali – Digitising a Queer Arab Future,” Khalid Abdel-Hadi, a Jordanian artist and the founder of a pan-Arab queer magazine My Kali, shares a harrowing account of being outed as gay by national media in 2007, when he was 16.

As a teenager, full of exuberance and curiosity, Abdel-Hadi posed shirtless for the first cover of the digital magazine, which was intended only for the eyes of his underground community; the magazine was saved as a PDF file on a CD and handed to those who attended an event, in typical 2000s digital fashion.

Abdel-Hadi says the image was hijacked by a Jordanian news outlet with a bigoted agenda. Many other publications followed suit with negative headlines and inaccurate reporting, he said in the essay, making him the face of a downtrodden community and an easy target.

“I acknowledged my orientation early on and I was very upfront about communicating with my family, specifically my mother. But then I was forced to deal with the public,” Abdel-Hadi recalls.

While five nations in the Arab region proscribe the death penalty for same-sex relations, homosexuality is not criminalized in Jordan. Despite this, it remains stigmatized and hidden in conservative Jordanian society, says Abdel-Hadi.

“I didn’t like the fact that they were trying to get me back into the closet or shame me, or to try to use me as a scarecrow toward others in the LGBTQ community,” says Abdel-Hadi of the press coverage at the time. He adds that the “horrific” experience made him even more determined to push forward with his digital magazine, which has now built a community of over 17,300 followers on Instagram.

Amna Ali

Jahshan is determined to show the full breadth of Arab identity, which is why the book calls on Black queer Arabs to share their experiences. ”It was really important to show the full diversity of the LGBTQ community,” he says.

One such voice belongs to Amna Ali, a Toronto-based writer who was born and raised in the United Arab Emirates to a Somali father and a Yemeni mother. In her essay, “My Intersectionality Was My Biggest Bully,” Ali reflects on her childhood as Black, queer, and Arab in a region that can be as homophobic as it is anti-Black.

The essay opens with a vivid description of Ali being beaten by her brother when she was 16, which she wrote was not an isolated incident. That episode was motivated by “honor” after her brother discovered messages she and her high school girlfriend had exchanged.

“I cried a lot [when] writing but it was very therapeutic. I was at a place where I was able to hold myself while I felt the pain,” Ali says of her creative process. She adds that she didn’t tell anyone about the abuse for years because she felt pressure to preserve her family’s standing in the community.

Read More: I Once Hid My Middle Eastern Identity. Being Cast in the Musical The Band’s Visit Changed That

In her essay, Ali recalled that her mother held her after the beating but did not speak to her about it because she disapproved of Amna’s queerness.

Ali never saw her mother as a victim of patriarchy, calling her “a proud carrier of the flame of oppression” in the essay, but she says her mindset has shifted as of late: “My father was this educated man who made the money who made sure that she needed him always… And my mother was a practically illiterate Yemeni woman whose father did not allow her to go to school past fourth grade.”

When Ali moved to Canada at the end of December 2021, a nation that fares relatively well on the global stage when it comes to LGBTQ+ rights, she says she finally felt safe and began to purge her emotions. “Boy, was I angry. I screamed and cried and punched my pillow so much,” she says, adding that she has now learned to be her own protector.

Zeyn Joukhadar

Another rare and impactful voice in the anthology belongs to Zeyn Joukhadar, a Syrian American trans author with a background as a semi-professional singer. His essay, “Catching the Light: Reclaiming Opera as a Trans Arab,” explores the beautiful journey he undertook to rediscover opera singing as a bass, rather than a soprano, when his voice changed.

“Music was a way for me to engage with my body that felt joyful even if it was difficult,” Joukhadar recalls. “Hearing my own voice when I was was a soprano was jarring. I knew there was something off about it but I didn’t understand why.”

While struggling to exist in the wrong body and learning more about his gender identity, Joukhadar says he experienced a sensation known as dissociation, which he says many trans people are familiar with. He describes this state of being as a shutdown in feelings—both physical and emotional—as a response to pain.

“It’s hard to have human relationships when you are so far away from your own feelings, your own body, and feel so separated from other people,” he says, adding that his transition is what broke the dissociation. This is why he advocates for trans people to receive life-saving medical care, including gender-affirming surgery.

Joukhadar says being trans and Arab are the same thing to him: “Both of them exist in my body at the same time, I cannot separate them out.” But he adds that being trans and racialized is a very different experience than being trans and white; Joukhadar has learned to find comfort in communities with other trans people of color.

If Jahshan’s anthology succeeds at one thing in particular, it’s that it shines a light on parts of the Arab world and its diaspora we don’t hear as much from. “We’re taking ownership of our stories and leading them rather than having people interpret them for their own gain,” he says.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Armani Syed at armani.syed@time.com