Five months after the Democratic nominee in one of the nation’s most competitive Senate races suffered a stroke, there’s still a lot to learn about his recovery.

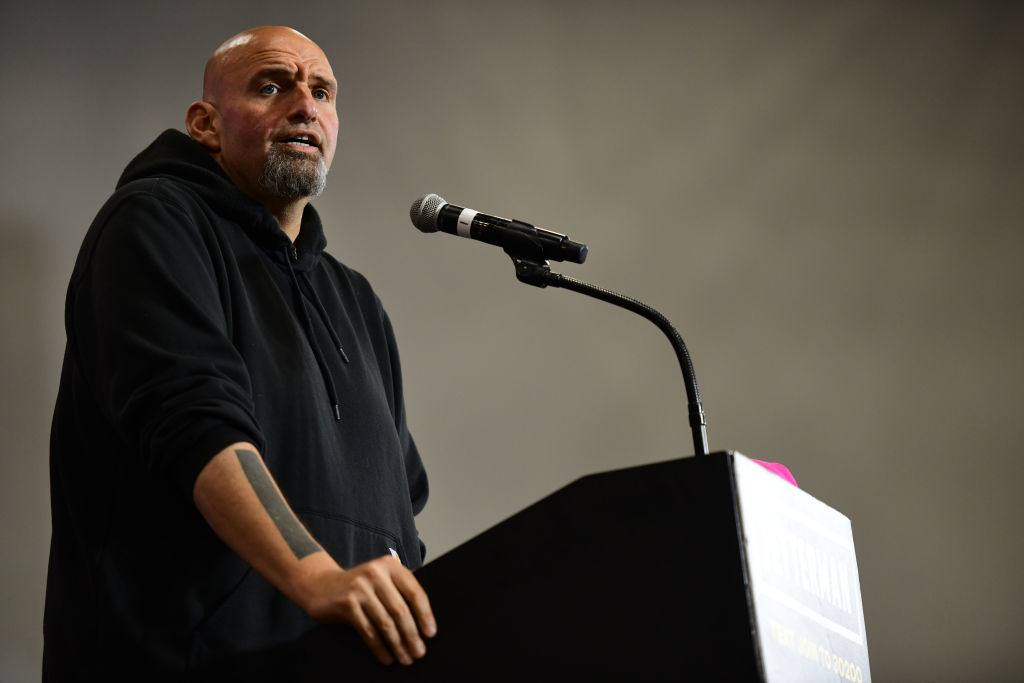

In the final weeks of the Pennsylvania Senate campaign, a key Republican attack against the state’s lieutenant governor, John Fetterman, has centered on his use of closed-captioning technology, which translates audio into text on a screen in real-time. He relied on the technology during an interview conducted Friday with NBC News, his first in-person, on-camera sit-down since his stroke in May.

“I sometimes will hear things in a way that’s not perfectly clear,” Fetterman said. “So I use captioning so I’m able to see what you’re saying.”

Fetterman also plans to use closed captioning for his upcoming debate with opponent Dr. Mehmet Oz, which is raising questions about Fetterman’s recovery.

Here’s we know so far.

What do we know about Fetterman’s health?

Fetterman suffered a stroke in May, just before winning Pennsylvania’s Democratic primary for Senate. In June, his campaign released a letter from his cardiologist that said that “he should be able to campaign and serve in the U.S. Senate without a problem.” He has not released information from his medical team since then.

Fetterman said earlier this year that his stroke was caused by a clot. The type of stroke in which a blood clot blocks blood flow to the brain is called an ischemic stroke—the most common kind of stroke and one of the leading causes of disability in America, according to a February report from the American Heart Association. Ischemic strokes can cause a variety of long-term conditions depending on which part of the brain connects to the clogged artery. According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, a stroke in the left hemisphere of the cerebrum can cause aphasia: difficulty finding the right words or understanding what others are saying, or both.

Does Fetterman have aphasia?

Fetterman’s campaign said in June that he did not have aphasia, and his communications director Joe Calvello told TIME in October that’s still the case. Calvello did not respond to a follow-up question about the differences between that condition and Fetterman’s.

Fetterman’s need to use closed-captioning technology mirrors some of the challenges faced by the estimated one-third of stroke survivors dealing with aphasia. Some aphasia patients might struggle to speak in complete sentences, while others might use incorrect words. During the 32-minute NBC interview, Fetterman mispronounced and confused several words before correcting himself. He often paused to read questions before answering. He repeatedly dodged inquiries about why he will not release his complete medical records.

Maria Town, the president and CEO of the American Association of People with Disabilities, says Fetterman’s use of caption technology doesn’t mean he wouldn’t be able to do the job of being a Senator. “People use captions all the time,” Town says. “It doesn’t have anything to do with with competence.”

“Concepts like competency, or fitness—these are extremely flawed concepts for many marginalized communities, including people with disabilities,” she added.

Dr. Kevin Sheth, the founding chief of the Division of Neurocritical Care and Emergency Neurology at the Yale School of Medicine, also says that just because Fetterman is experiencing difficulties with speech, that doesn’t mean he is having other cognitive issues. “If you have a blockage in the blood vessels that supplies the part of the brain that plays an influential role in language, then you’re going to have trouble with language,” Sheth says. “If it’s the parts of your brain that control your strength and coordination in your limbs, then you’re going to have weakness or paralysis. The deficits that you have depend on the part of the brain that’s downstream from where the blockage in the blood supply was.”

How does closed-captioning technology help him?

In his NBC interview, Fetterman blamed his challenges on “auditory processing issues” and indicated that he struggled to understand what he was hearing shortly after his stroke, but that his ability to do so has improved since then. Captioning, Fetterman said, helps him be precise.

Oz’s campaign manager suggested Fetterman wouldn’t be able to use closed-captioning on the Senate floor. But according to Senate rules, Fetterman would likely be able to use the technology without a vote if he needed it. A 1997 resolution allows individuals with disabilities to bring necessary supporting aids and services onto the floor. The Sergeant at Arms could allow an accommodation as long as it doesn’t create significant cost or difficulty for Senate operations. Senate Chamber regulations also authorize the Sergeant at Arms to allow on the floor any “mechanical equipment and/or devices . . . necessary and proper in the conduct of official Senate business and which by their presence shall not in any way distract, interrupt, or inconvenience the business or Members of the Senate.” Tim Johnson, for example, former Senator from South Dakota, used a mechanical wheelchair on the floor without Senate action.

Asked by NBC if he would need similar accommodations in the Senate, Fetterman replied, “I don’t think it’s going to have an impact. I feel like I’m going to get better and better every day and by January, I’m going to be much better and Dr. Oz is still going to be a fraud.”

Is Fetterman’s stroke recovery typical?

“As we’ve said over and over again, John is healthy and he also still has a lingering auditory processing issue that his doctors expect will go away,” Calvello wrote in a statement Thursday. “The whole point of the NBC News interview was to show how John is conducting this campaign and doing his interviews.”

Scientists and doctors are still working to understand stroke recovery, which varies considerably from patient to patient. Outcomes can range from full recovery to permanent disability, and many factors—such as physical therapy, rehabilitation, and lifestyle changes—can affect the process. But in general, recovery tends to follow a particular pattern. “If I draw a graph, I would draw one of those curves where you get steep recovery early, and then over time, the slope can still be there, but it starts to flatten out,” says Sheth. “The recovery between month 14 and 15 might be pretty small, whereas the recovery between two weeks and four weeks might be much bigger.”

When it comes to aphasia in particular, some research indicates that the bulk of improvement happens in the first three months, though survivors can continue to see slow improvement for years, just as they can with all symptoms after a stroke. “If a person at five months has a certain amount of deficits, it’s not like those deficits are going to disappear the next week,” Sheth says. “It’s gonna take some time.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Mini Racker at mini.racker@time.com