There’s wide agreement that the protests shaking Iran—led by women and persisting across the nation for more than six weeks now—are different than those that have come before. But the forces the regime is sending to confront the protestors appear to be different, too. Perhaps tellingly.

As Iranians circulate videos and photos of the confrontations, they point out what some describe as evidence of a state security apparatus showing signs of disquiet, if not disarray. That security apparatus remains brutally lethal, so far killing at least 230 people and injuring thousands. But it’s also grown motley. Along with plainclothes thugs who snatch women from public streets, it includes uniformed men hiding behind ski masks and small children in body armor.

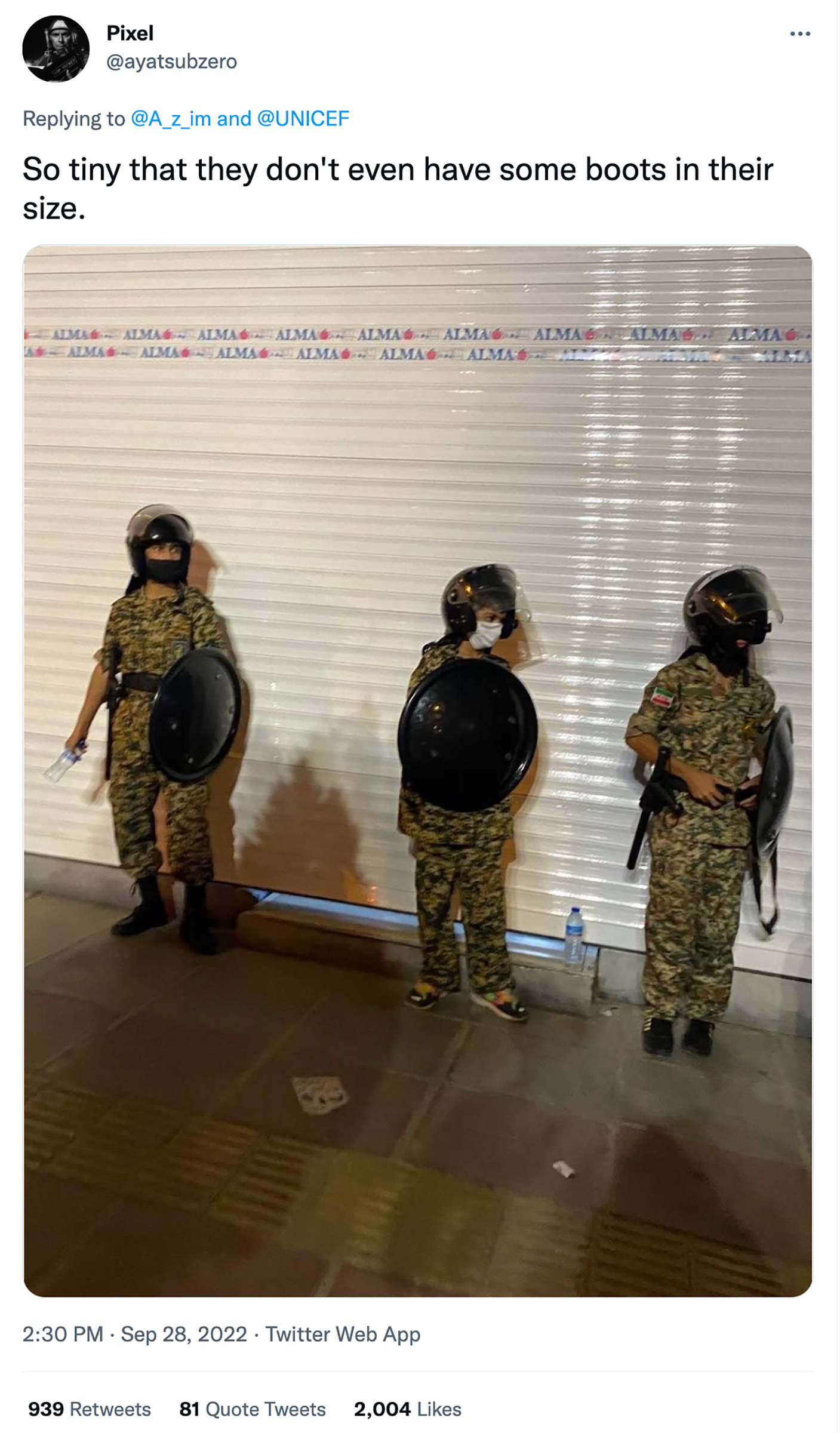

Images of children in riot gear popped up days after 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died in the custody of Tehran’s “morality police” on Sept. 16. It was her death that set off spontaneous protests in at least 80 cities, immediately stretching thin the forces available to confront them. The kids—whom some Iranians commenting in social media describe as wards of the state—appeared to have been posted on urban streets to fill a gap, a dubious show of “presence” while adult police scramble from one protest outbreak to the next.

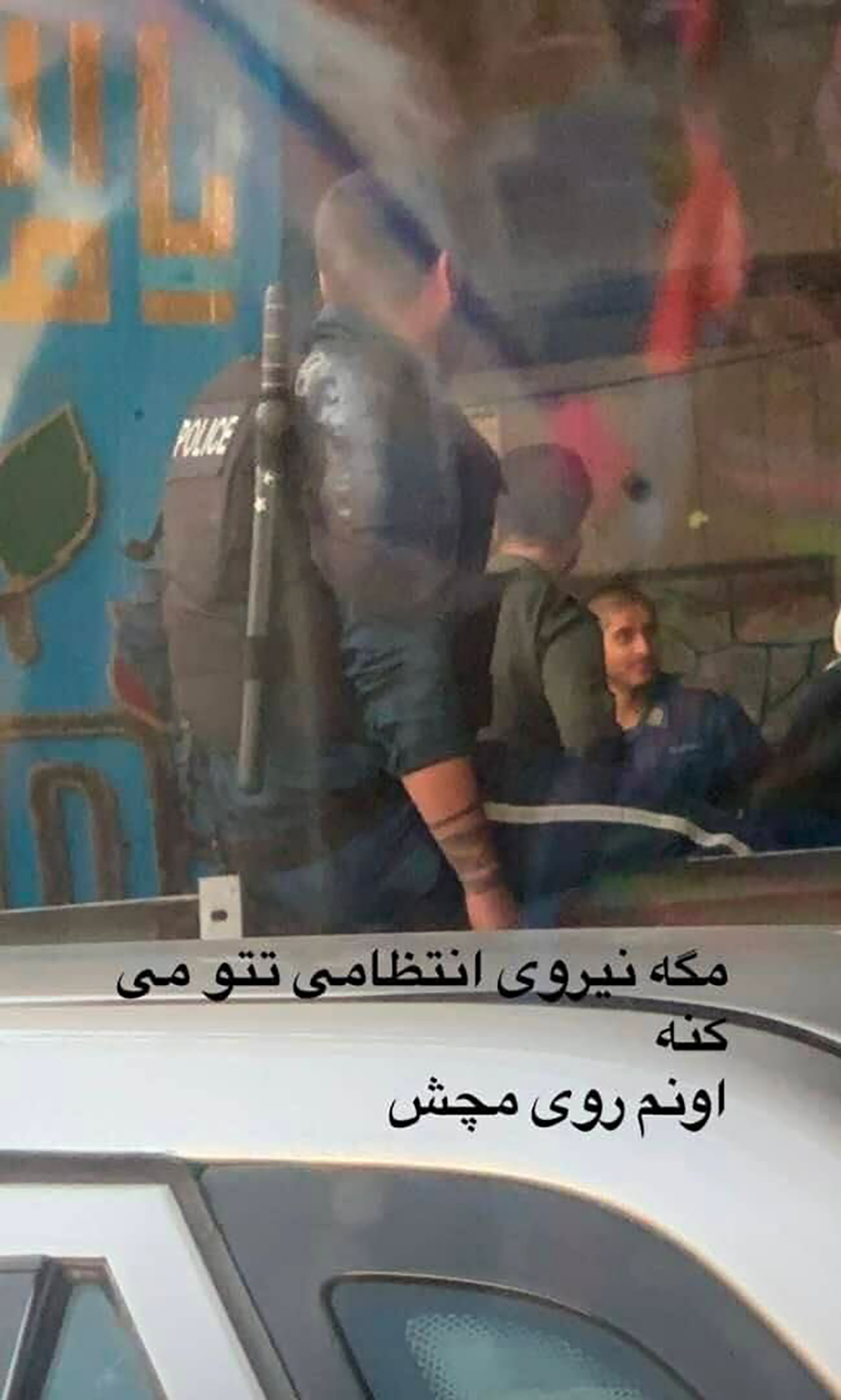

Having lived through three mass protests in the last dozen years—in 2009, 2017-2018, and 2019—Iranians are only too familiar with how the state answers dissent. They can tell you that for decades the largest motorcycle a civilian could buy in Iran was 250cc. More powerful bikes were reserved for security forces, to overtake and intimidate. Iranians also know that tattoos—regarded by the Islamic Republic as decadent expressions of “Westoxification”—are forbidden for members of police, security, and military.

So when an image of a police officer with ink (on his lower arm, where it’s visible) was posted on Telegram on Oct. 12, it was understood as evidence the regime has abruptly relaxed its standards.

“They’re recruiting street children, teenagers, and criminal elements,” says Hadi Ghaemi, director of the New York-based Center for Human Rights in Iran. “They’re short, short on manpower.”

And the manpower available does not always show its face. Ordinarily, it’s protestors who take pains to hide their features—fully aware that Iran’s security services make use of facial recognition technology. The same surveillance technology was being used to identify women judged to be wearing their headscarves too loosely, in a stepped-up enforcement of “mandatory hijab” rules that Iran’s hardline President Ebrahim Raisi announced in August. Iranians’ national ID cards have carried biometric data since 2015.

But now security forces are covering their faces in the streets. Uniformed men wearing ski masks have emerged in the stream of images that pour out of Iran during the few hours a day when the government allows the internet to operate. In one video, several militia wear ski masks as they rest outside a business. In recent days, witnesses in Iran’s sprawling capital report that a majority of forces on the street had covered their face in some way.

Their apprehension over being identified may provide a clue into the key question—how deeply the revolt is reaching into Iranian society. People inside the country speak of a tectonic shift in the population. Protests have broken out in districts of Tehran that traditionally produce the militia relied upon to put down protests—not generate them. Last week in Tehran, the protests reached a high-rise district that is home to military families, another ominous development for the regime.

Read More: Here’s How to Support Protesters in Iran

Ghaemi spoke of a colleague with relatives in Mashad, the second-largest city in Iran, who report that the family members of the regime militiamen known as basij are lying low, “turning off lights, not letting people go in and out. They’re really fearful that people are going to attack them.” Numerous basij headquarters have been set alight, and graffiti has appeared in Tehran singling out specific security forces members as “murderers.” Message platforms have circulated threats to men in civilian clothes who are believed to be security forces. One post included the alleged security official’s ID card, including phone number and national identification number.

The revolt shows no sign of flagging. In Amini’s majority-Kurdish hometown of Saqez on Wednesday, thousands defiantly marched to her grave to observe the 40th day since her death, a deeply significant milestone in Shi’a Islam. The process repeated the next day, for 16-year-old Nika Shakarami, killed after being arrested protesting Amini’s death. On Thursday, the funeral of another protester in the northwest city of Mahabad led to the burning of the governor’s office. As a woman sat facing a handful of riot police on a Tehran street, a video shot from a passing car picked up what she was shouting to them: “I’ll hit you so you’ll run like rats!”

There is also no shortage of signs that Iran has supplemented its security apparatus with lightly trained newcomers. When human rights lawyers gathered to protest outside the Iranian Bar Association on Oct. 12, they observed that the forces that dispersed them also attacked the police already cordoning the gathering. “The basic evaluation is that they’re really rookies,” Ghaemi says.

When Iranians manage to get online, they exchange evidence supporting that conclusion. Among the videos circulating is one of anti-riot forces jostling to watch an arrest in a swarm that assures mass casualties if they come under attack. In another, young people laugh and applaud as they record anti-riot police struggling to control their motorcycles. “Look, I told you!” one exclaims in Persian. “They don’t know how to drive at all.”

One photo shows an anti-riot officer approaching Tehran’s Baharestan Square with his uniformed authority undermined by his purple backpack.

Augmented forces are not necessarily less dangerous. Untrained police—if they are police at all—may be more likely to use live fire out of panic, or worse. In 2009, when as many as a million Iranians peacefully took to the streets to protest a stolen election, the 45,000 basij militia on hand were judged insufficient to the task. At that point, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which reports directly to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, looked to local jails. “We had identified and monitored 5,000 violent criminals and, at first, ordered all of them to stay at home when there was any protest,” General Hossein Hamedani told reporters. “But later I thought: why not employ these thugs? So I organized them in three regiments to engage with the protesters on our behalf. They proved me right … if we want to train Mujahids [holy warriors], we need these types of violent people who are not afraid of a few drops of blood.”

Embedded in the boast is the implication that, more than a dozen years ago, a significant portion of the uniformed forces could not be counted upon more than a dozen years ago. The same question drives the close attention to the recruits pressed into service to meet the #MahsaAmini revolt, which appears to have reached deeper into a society that’s grown poorer and more alienated from a regime less that’s grown only more oppressive. “It could mean that they’re worried their own trained forces will not follow orders,” Ghaemi says. “They need their most loyal to go to maximum violence. They need people who will shoot on orders.”

Read More: ‘People Want Change.’ Oscar Hopeful Zar Amir Ebrahimi on Holy Spider and Iran’s Struggle for Freedom

The human rights advocate says he worries that Khamenei—notorious for favoring an iron fist—will answer chants of “Death to the dictator” by ordering a massacre on the order of Tiananmen Square, where in 1989 China extinguished a pro-freedom movement by killing hundreds, if not thousands. Such fears rose this week, when an apparent terror attack killed 15 people at a shrine in the city of Shiraz on Wednesday. Though Islamic State claimed responsibility, the regime attempted to link the attack to riots. The Supreme Leader was alluding to Iran’s security forces on Thursday when he tweeted: “the responsible sectors will definitely prevail against the criminal conspiracies of the enemies, God willing.”

Indeed, by the brutal arithmetic of the ongoing protests, the death toll indicates a relative restraint by riot police, notes Ali Vaez, the Iran analyst for International Crisis Group. In their leaderless spontaneity, the revolt resembles the nation-wide protests that erupted four years ago after a fuel prices hike. Vaez notes that the current death toll of 230 was stretched across a month, “whereas in 2019 they killed north of 400 people in two days.” (Some estimates surpass 1,000.)

“They haven’t even deployed the IRGC yet,” he says.

Vaez says it may be the protests that are understaffed. While events like funerals can produce masses, many demonstrations unfold like what one Iranian described witnessing in Tehran this week—a few dozen young people block traffic and chant, then, when riot police arrive, duck into storefronts that, in revolts past, would have been shuttered by merchants worried about damage. By remaining open, are the merchants signaling solidarity with the protestors who move, “amongst the people as a fish swims in the sea,” as Mao described an insurgency? Vaez says that may be wishful thinking.

“You have young people in the street chanting, ‘The regime is too brutal. It will continue to be brutal until you join us.’ Which indicates there is reluctance for the great strata of Iranian society to join in,” he says. “The fact that the riot police is overstretched is less significant than the fact that the middle class is still reluctant to join the fight.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Video by Andrew D. Johnson at andrew.johnson@time.com