The U.S. may have the highest level of income inequality of the G7 nations, but new research suggests that disparity has actually stabilized over the last decade, thanks to rapid growth in wages for the lowest-paying jobs.

It just may take a while for the average American to feel it.

A pair of researchers from Harvard and MIT examined data from the period between 1980 and 2020, and found that income inequality peaked in 2012 and then began to stabilize even though many of the drivers of rising inequality—such as a decline in union membership—have persisted. “After decades of rising inequality, overall earnings inequality stopped growing, and possibly declined, since 2012,” according to the research paper, titled Rapid wage growth at the bottom has offset rising U.S. inequality. That could be good news for the fight against inequality, but the gains are hardly permanent and could be wiped away if the economy spirals.

“It’s got me feeling very cautiously optimistic,” says Clem Aeppli, a Harvard PhD student and co-author of the research article, which was published on Monday in the competitive PNAS journal. “Optimism in the sense that maybe the increase in inequality we’ve observed since the 1980s is not inevitable.” But Aeppli says he is also “incredibly cautious…because the stabilization in inequality seems so reliant on these very fragile market conditions.”

Read More: We Tried to Find the Most Equal Place in America. It Got Complicated

Tracing income inequality can be especially messy, but the researchers say they pulled together multiple measures of earnings—from household and business surveys to Bureau of Labor Statistics data—which they say all told a similar story: Income inequality is declining as growth for low-wage workers outpaces middle- and high-wage workers.

“It’s unexpected good news for those of us who have been studying inequality trends for a while,” says Nathan Wilmers, an associate professor at MIT Sloan and co-author of the research paper.

Separate data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta shows that as of August, the bottom quartile of U.S. earners saw a 7% increase in wages over the last year, while those in the top quartile saw wages increase 4%. According to Wendy Edelberg, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution and director of The Hamilton Project, wage gains have been greatest for the leisure and hospitality sector and the retail trade sector, while workers in other industries have not seen the same benefits.

“We’ve seen big declines in real wages for every sector except those two,” she says, partly because of pandemic and inflationary pressures. “And they happen to be pretty low wage sectors.”

Read More: Why All Inequality Is Not Created Equal

While the research suggests individual income inequality is shrinking, figures from the Census Bureau present a less optimistic picture for American households, which are facing current inflation levels of 8.3%, putting pressure on living costs. The Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey, released Oct. 4, found that household income inequality was “significantly” higher than its 2019 estimate (based on a calculation of the Gini index, a summary measure of income inequality used across the world). Contrary to the two scholars’ findings about individual income, the Census Bureau found that household income inequality increased over the last year for the first time since 2011 due to declines in real income—which takes inflation into account—at the bottom of the income distribution. The scholars attribute this difference to changes in the Bureau’s data collection and processing methods. “That report is looking at household income inequality rather than inequality in individual earnings,” Aeppli says. “It’s a different unit of analysis and different quantity. And even when we correct for that difference, we still observed that household income inequality seems to be stabilizing in the last decade—it just isn’t as pronounced.”

Research in related fields seems to support the scholars’ findings. As earnings grow for low-wage workers, the number of Americans living below the poverty line has also decreased, says Chris Wimer, director of the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University. A number of policies designed to offset the impact of rising prices have contributed, including employment expansions, stimulus payments and the child tax credit of 2021. “But some of those policies are going away,” Wimer says, “so families coping with inflation no longer have the same policy support.”

Read More: What You Need to Know About the Inflation Reduction Act

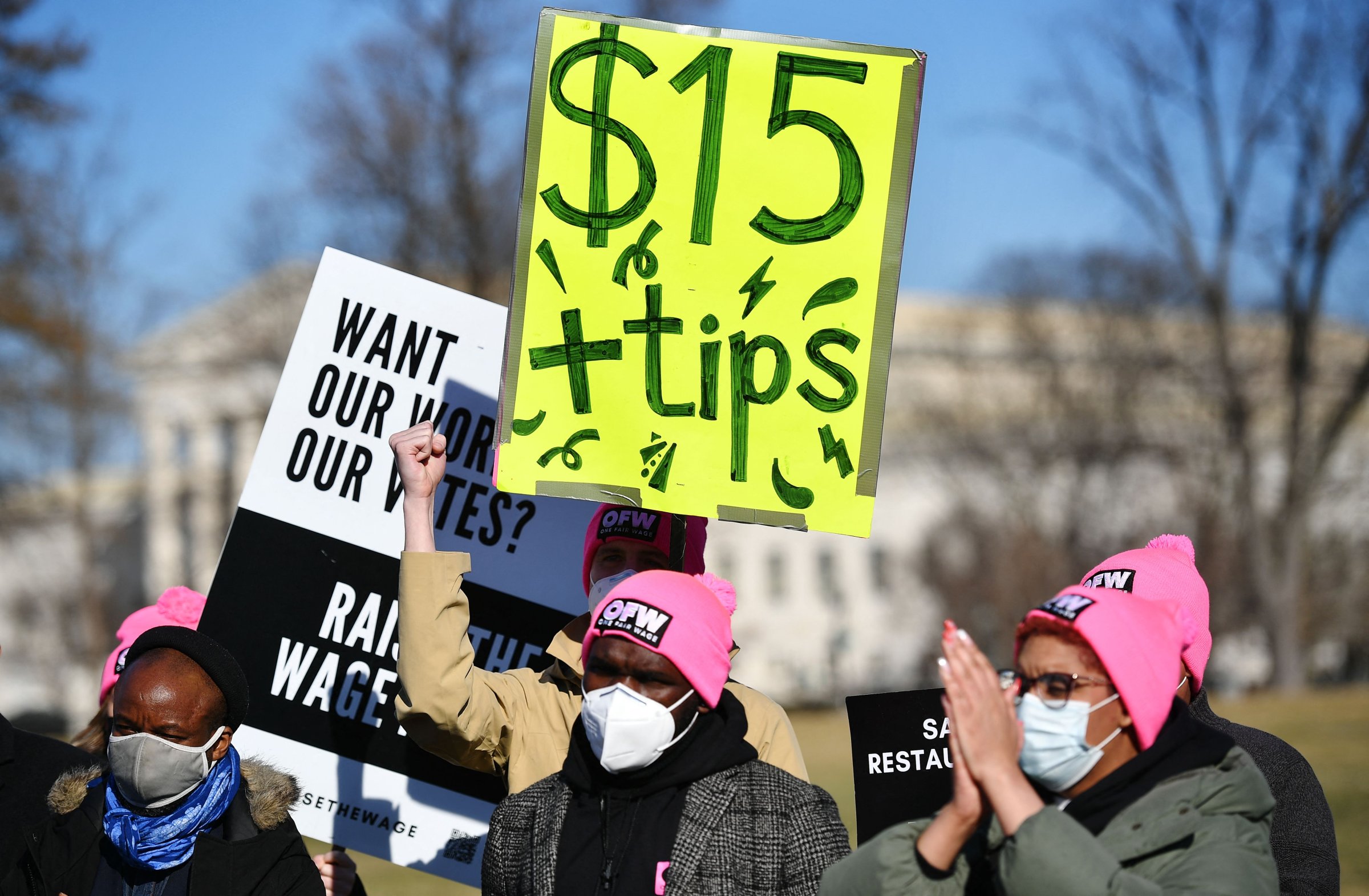

However, the Harvard and MIT study suggests that policy measures have had less of an impact than market dynamics. It argues that a tight labor market is what’s driving these changes in inequality rather than other factors like minimum wage legislation, labor action or a shortage of workers. The early months of the pandemic put frontline workers dealing with the public face-to-face at the most risk, and saw workers resigning in droves, particularly in the food services and retail industries. Their analysis found that raising minimum wages to $15 an hour would, perhaps unsurprisingly, increase earnings at the bottom, though most cities did not increase minimum wages in 2021. However, labor shortages meant that some employers were offering higher wages in order to get staff in these roles.

Read More: Why We Should All Be Worried About ‘Chokepoint Capitalism’

Despite the research paper’s hopeful indicators, experts say we’re still nowhere near making a dent in overall inequality. “We’re not even in the ballpark, let alone within spitting distance, to the kinds of changes we need to make,” the Brookings Institution’s Edelberg says. Overall income inequality, she argues, is not just driven by hourly wages—as the report tracks—but also by who’s working and how many hours they are working.

In fact, it may take years—or decades—for low-wage workers to start feeling the effects of declining income inequality, even if the downward trend continues. As the nation deals with the worst inflation in 40 years, prices on just about everything have skyrocketed, from living expenses to gasoline to food. “We’ve seen positive movement with the lowest wage sectors having the biggest gains,” Edelberg says, “but there’s no way I think we want to declare mission accomplished.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Nik Popli at nik.popli@time.com