Paramedics are lifelines in U.S communities, responding to all kinds of medical emergencies. And yet, the history of the emergency medical services (EMS) is little-known.

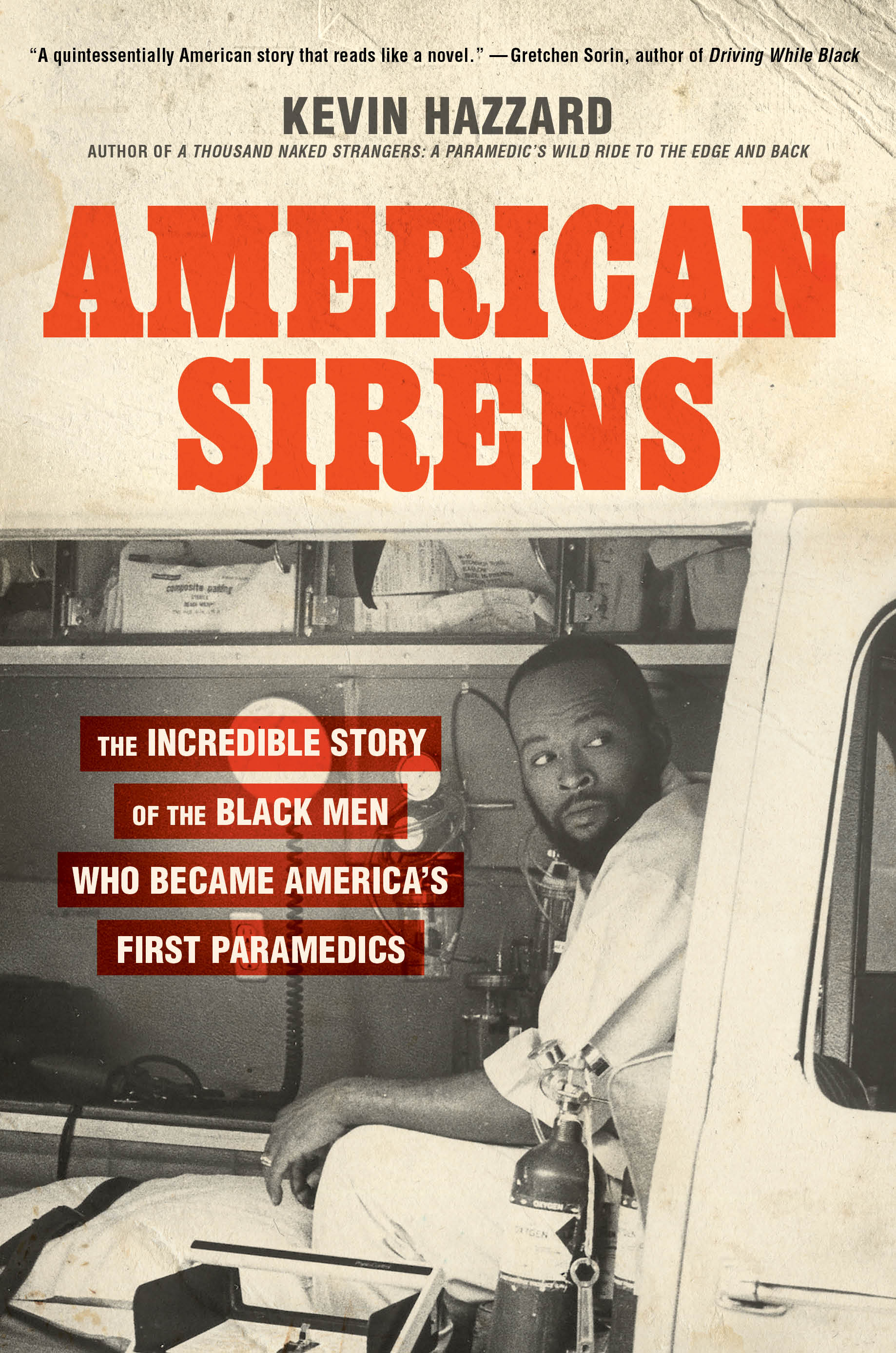

In American Sirens: The Incredible Story of the Black Men Who Became America’s First Paramedics, author Kevin Hazzard, a former paramedic, spotlights the Black men in Pittsburgh who pioneered the profession and formed a model for emergency medical services that other cities copied.

In 1966, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) published a white paper that was a damning indictment of the nation’s emergency response system. “Essentially, paramedics weren’t plentiful enough to be there when you needed them and then weren’t well trained enough to be of much use when they were there,” Hazzard says.

Ambulances were, in some cases, hearses that were driven by undertakers from the funeral home that would later plan the patient’s funeral. In other situations, the sick and injured might be tended to by police officers or volunteer firefighters who were not trained to provide emergency care. Americans were more likely to survive a gunshot wound in the Vietnam War than on the homefront, according to the NAS report, because at least injured soldiers are accompanied by trained medics. “In 1965, 52 million accidental injuries killed 107,000, temporarily disabled over 10 million and permanently impaired 400,000 American citizens at a cost of approximately $18 billion,” the report said. “It is the leading cause of death in the first half of life’s span.”

This lack of emergency care hit home for Peter Safar, an Austrian-born anesthesiologist at the University of Pittsburgh and a pioneer of CPR who helped to develop the modern hospital Intensive Care Unit (ICU). He lost his daughter in 1966 to an asthma attack because she didn’t get the right help between her house and the hospital. So he coped with the loss by designing the modern ambulance—including the equipment inside, plus its paint scheme. Perhaps most crucially, he also designed the world’s first comprehensive course to train paramedics.

The first people to take the course in 1967 were a group of Black men who were in Freedom House, an organization that originally provided jobs delivering vegetables to needy Black Americans. At first the idea was to switch the delivery service from delivering food to driving people to medical appointments. But, within eight months, the drivers were trained to handle emergencies including heart attacks, seizures, childbirth, and choking. Their first calls took place during the uprising following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968.

And data showed that the training worked. One 1972 study of 1,400 patients transported to area hospitals by Freedom House over two months found the paramedics delivered the correct care to critical patients 89% of the time. By contrast, the study found police and volunteer ambulance services delivered the right care only 38% and 13% of the time, respectively. One Freedom House member, Nancy Caroline, wrote a textbook on EMS training that became the national standard.

Despite the success of Freedom House, the city nixed the program in 1975. Pittsburgh Mayor Peter Flaherty thought he could create a better system and replaced Freedom House with an all-white paramedic corps. Hazzard tells TIME that he believes racism was at play. As he puts it, “What other reason could he have for not wanting this organization, which was so successful and was a model around the country and around the world, other than the fact that they were an almost entirely Black organization.”

The real story “doesn’t make the city look good,” Hazzard says, so that’s why he thinks the story of the nation’s first paramedics is not better known. But Hazzard believes there are lessons in this story that are useful for all professions, not just paramedics. Many of the Freedom House participants went on to get master’s degrees, Ph.D.s, or medical degrees—or pursued careers in politics or the upper echelons of police, EMS, and fire departments.

“These were really successful people who came from nowhere and where it all began was an opportunity in 1967,” Hazzard says. “All it took for a group of young men that the world had written off was one opportunity, and they never looked back from that point. Anyone can reach great heights. They just simply need a single opportunity.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com