A new Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) rule is setting up a major clash between conservative states and the federal government, as Republican lawmakers vow to fight the policy that the VA will provide abortion services even in states that have outlawed the procedure.

Under the new rule, which took effect on Sept. 9, the VA will provide abortion counseling and abortions in cases of rape, incest, or when a pregnancy threatens the patient’s life to veterans and their eligible family members. This represents a historic change: the VA previously did not provide abortions for veterans under any circumstances and did not allow its providers to counsel patients about the procedure.

The move is a direct result of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade this summer, which set off a wave of abortion bans and restrictions around the country. VA leaders said those restrictions created “urgent risks” for veterans and forced the agency to act. “This expansion is a patient safety decision first and foremost,” Dr. Shereef Elnahal, VA under secretary for health, told members of the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee on Thursday. “It is important to emphasize that VA is taking these steps with our primary mission in mind: to preserve the lives and health of veterans.”

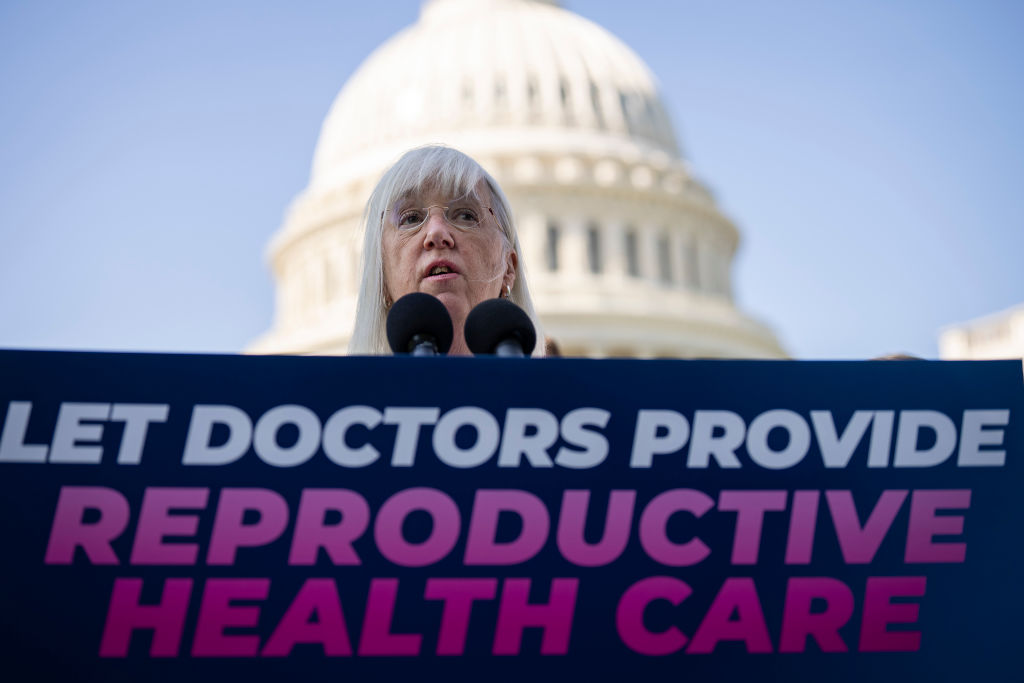

The policy was cheered by Democrats, who have been pressing President Joe Biden to find ways to expand abortion access since the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization eliminated the federal right to abortion. They said they hoped VA’s move would have broad appeal, given that the rule only allows for abortions in circumstances that track with other federal policies. Democratic Sen. Patty Murray of Washington called the change a “common sense policy” at a news conference on the topic last week, while Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois, who lost her legs serving in Iraq, questioned why the government would be comfortable letting her use her body for war but not for her choice of how and when to start a family. “When is it that American women have the right to bodily autonomy?” she asked.

Republicans disagree. Many states that have enacted near-total abortion bans do not have exceptions for rape and incest, so conservatives argue the VA is overreaching its authority. Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall said last week he would enforce his state’s abortion ban, which outlaws all abortions except in cases that threaten the life of the pregnant person, against any practitioner who violates it. “I have no intention of abdicating my duty to enforce the Unborn Life Protection Act against any practitioner who unlawfully conducts abortions in the State of Alabama,” he said in a statement. “The power of states to protect unborn life is settled.” Arkansas Attorney General Leslie Rutledge, whose state abortion ban also only allows for abortions in life-threatening cases, similarly told TIME she would enforce her ban despite the VA policy. “I stand ready to challenge the Biden Administration for trying to circumvent Arkansas law,” Rutledge said in a statement.

The Hyde Amendment prohibits federal funding for most abortion-related services, but it allows for similar exceptions to the VA’s rule—and it only applies to funds appropriated for the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, not the VA. Republicans argue the VA’s policy violates other laws, including the Veterans Health Care Act of 1992, which excluded abortions from the medical care the VA was allowed to provide. Democrats counter that the Veterans Health Care Eligibility Reform Act of 1996 allows the VA secretary to “furnish hospital care and medical services” determined to be “needed,” including abortion.

VA officials and legal experts say the agency is is on solid legal footing as it institutes the new policy, particularly due to the legal principle of federal preemption. “The federal government gets to make law and states can’t say, ‘we don’t want to follow that,’” says David Cohen, a law professor at Drexel University. “So a state that tried to sue to say the VA can’t do this would be contravening that fundamental principle of American law.”

The outcome of the legal debate could affect thousands of women seeking care. About 260,000 women veterans of reproductive age live in states with severe abortion restrictions, according to Kayla Williams, a RAND Corporation researcher and former director of the VA’s Center for Women Veterans, who testified at the hearing. She estimated that about 96,200 VA patients could be affected by the policy change. Elnahal said he initially expects about 1,000 VA-supported abortions to be performed a year, but that could grow in future years as the number of women veterans is increasing rapidly.

Republicans said during Thursday’s committee hearing that they would support legal challenges to the policy and threatened to go after the VA’s budget if they retake control of Congress in November. “This is not only wrong, it’s illegal,” said ranking committee member Rep. Mike Bost, a Republican from Illinois. He said he was working with colleagues on the House appropriations committee and in the Senate on potential sanctions. “Abortion is not health care, no matter what those on the other side of this issue may feel.”

Legal and logistical challenges

Regardless of whether the VA policy is challenged in court, it will be complex to implement, and it’s unlikely that its providers will be ready right away to provide a range of abortion services.

One of the biggest challenges is the fact that the VA is essentially building infrastructure for the plan in real time. The VA has not said when its facilities will start providing abortions. Elnahal told lawmakers the agency is working to ensure that facilities have proper staffing and training to carry out the policy, making pregnancy testing available at all locations, and conducting a survey of the availability of ultrasound machines. “We believe medication abortion will be the first available and most common type of abortion provided, so we are working to ensure providers have access to training as well as the needed medications,” he said.

If the VA is not immediately able to provide needed care, Elnahal said veterans and beneficiaries can use community providers or travel to other community or VA facilities, and the VA will cover the cost of that transportation where applicable. But the legal landscape is complicated. For those providers working at VA facilities on federal property, Elnahal said “they will be protected under federal supremacy and the full force of the federal government will be there for them should they be challenged on that.” But the same legal protections would “not necessarily be available” for providers working in non-VA facilities in states that have banned abortion, he said.

This could make it difficult to find community providers willing to help in states that have outlawed abortion, especially as many abortion clinics in those states have closed or stopped offering the procedure. “As the abortion infrastructure and the infrastructure for care across the country continues to shut down as a result of state level bans, VA is going to have a really hard time implementing this policy,” Lindsay Church, executive director of Minority Veterans of America who testified at the hearing on Thursday, told TIME.

The Constitution does provide some protections for people traveling to federal land to conduct federal business, Cohen and other legal experts say. The 14th Amendment’s privileges or immunities clause could be used to protect patients or providers if states try to go after people for providing abortions at VA facilities. But Rachel Rebouché, dean of Temple University’s Beasley School of Law and an expert on reproductive health law, says the clause has been interpreted narrowly in the past and it’s unclear how far the protections would go.

Even if states don’t take that legal route, Rebouché says they have the power to make doctors’ lives difficult if they participate. “States could target you in other ways. They could say that it’s unethical, or they could attack your license. State medical boards have really broad authority to define what is ethical practice,” she says.

“It really is going to shine a spotlight on tensions between federal and state regulations,” Rebouché adds. “It really is going to test our fundamental assumptions about federalism, about how states should treat each other, about the role of federal law in the abortion arena.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Abigail Abrams at abigail.abrams@time.com