W.E.B. Du Bois is perhaps best known for introducing the term “double consciousness” into the lexicon of the Black experience. The term described the duality of being a Black American—neither fully African nor completely American, an enduring “problem” to be fought over in times of war and wrestled with during times of peace. The duality at the heart of double-consciousness impacts the entire American project. America itself possesses dueling identities, reflecting warring ideas about citizenship, freedom, and democracy. There is the America that proudly identifies itself as reconstructionist, home to champions of racial democracy, and there is the America equally proud of being redemptionist, a country defiantly committed to maintaining white supremacy by any means necessary. Since the birth of the nation, its racial politics have been shaped by an ongoing battle between reconstructionist America and redemptionist America.

More than any other Black thinker of his generation, Du Bois identified Reconstruction, the years of hope and pain following the formal end of slavery, as America’s most important origin story. Du Bois co-founded the NAACP in 1909, played a key role in its subsequent work, and wrote an edited a prodigious number of important books and essays. But in 1935 he wrote his most important book yet, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880, about the dual Americas that briefly coalesced as one in the aftermath of a bloody Civil War. Du Bois grew obsessed with attempting to comprehend the moral failure behind the rise of white supremacy. He viewed Reconstruction as more than just a missed opportunity. Du Bois considered the decades following the Civil War to be a second founding. One that gave painful birth to a new America that expansively redefined freedom beyond the parameters of the old. America’s Reconstruction era, which lasted a little more than three decades, from the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 to the white riot in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898, was a historical watershed.

Black Reconstruction exposed the myths and lies of “Lost Cause” histories that presented the period after slavery’s end as a horrible mistake that required the heroic intervention of the Ku Klux Klan to make right. Throughout the early decades of the twentieth century, the Dunning School of Reconstruction history, named for the white Columbia University historian William Archibald Dunning, was taught from coast to coast. At Harvard University in the 1930s, the young future president John F. Kennedy took these lies to heart.

By June 11, 1963, President Kennedy had clearly reconsidered the merits of the Lost Cause. That day, he gave his first major nationally televised speech in support of racial justice and equality. A few hours later, Medgar Evers, a Mississippi civil rights activist, was assassinated as he emerged from his car in his own driveway, shot in the back by a white supremacist. “I don’t understand the South,” Kennedy observed to a close aide. “I’m coming to believe that Thaddeus Stevens was right.”

Kennedy’s invocation of Stevens, a Radical Republican who believed in political and social equality wrought from the punishment and subjugation of Confederates as well as active and passive supporters of the slave power, exemplifies Reconstruction’s afterlife during the civil rights era. A son of Vermont turned Pennsylvania Republican, Stevens chaired the House Ways and Means Committee during the Civil War and became a most powerfully effective spokesperson in support of Black citizenship after the war. He battled Andrew Johnson’s embrace of white supremacy and looked upon Radical Reconstruction as a method of “perfecting a revolution” intended to irrevocably break the former Confederacy’s efforts to restore racial inequality by other means. Aware of the reports that white supremacists, just one year after the end of the Civil War, were “daily putting into secret graves not only hundreds but thousands of the colored people,” Stevens became one of the architects of Reconstruction policies aiming to ensure federal protection of Black voting rights, to prevent ex‑Confederates from resuming their political domination in the South, and to put an end to widespread anti-Black violence in the former Confederate States. Redemptionists would never forgive Steven for his stalwart belief in Black humanity and made sure to tarnish his legacy to all who would listen, including the young JFK. Like Kennedy, segments of American society during the civil rights era tried to square the false history they had been told regarding “Negro domination” in redemptionist histories of the Reconstruction era with the violence, bad faith, and blatant racism gripping the nation.

For Black America, Reconstruction remains a blues-inflected poem chronicling the perils and possibilities of Black humanity, democratic renewal, and the pursuit of citizenship and dignity amid the ruins of a world ravaged by racism, war, and violence. Du Bois’s work serves as a historical correction, political inspiration, and policy provocation. And the problems that gave rise to these debates, in truth, have never really ended. The racial violence, political divisions, cultural memories, and narrative wars that emerged from the Reconstruction era continue in our own time. The “hate and blood and shame” are still deeply embedded in twenty-first-century America.

The First Reconstruction era, 1865 to 1898, was followed by decades of Jim Crow, with its mendacious principle of “separate but equal.” The Second Reconstruction spanned the heroic period of the civil rights era— from the 1954, Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s April 4, 1968, assassination.

In our time we have come to the Third Reconstruction, the period from the election of Barack Obama as president in 2008 through the recent Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests and all that they have entailed. The debates, conflicts, and divisions of the Third Reconstruction have been the most volatile yet. The global health pandemic that started in early 2020 revealed beyond doubt how deeply the racial disparities in society have affected Black lives. That disparity is still rooted in the world America built just after the end of slavery.

The BLM movement inspired rebellions against police brutality both at home and abroad. It became the largest social protest movement in American history, representing a continuation and expansion of reconstructionist segments within the nation. Joe Biden became president following the most racially divisive presidential campaign season in US history, and the issues that arose reflected the continuing evolution of redemptionist impulses in our own time. The transformation of President Joe Biden is telling. A generation before taking the Oval Office, Biden had supported a redemptionist notion of Black citizenship; by the time of the 2020 election he had become an advocate of reconstructionist policies. He thus exemplified how politicians from the First Reconstruction era to the present have often moved back and forth between these two poles, at times straddling both of them simultaneously.

When two Democrats won Georgia’s runoff elections on January 5, 2021, the party took a slim majority in the U.S. Senate. One of those victors, Raphael Warnock, became the first Black person from Georgia in American history to be elected senator. When he spoke, his words evoked the promise born from the height of the Reconstruction era, with its triumphant scenes and its hopes for Black power. In the 2020 and 2021 elections, Black women, including former Georgia state legislator Stacy Abrams whose voting rights organizing helped make Warnock and Ossof’s victories possible, took a leading and very visible organizing role, especially in advocating voting education and bringing the issue of criminal justice reform into the foreground. Not to mention that a Black woman, Kamala Harris, was elected vice president of the U.S. for the first time.

The white riot of January 6, 2021, at the U.S. Capitol Building is impossible to understand without reference to earlier, yet strikingly similar, efforts during the First Reconstruction period. In both cases, there were attempts to violently overthrow democratically held elections won with the aid of Black votes. To fully comprehend the challenges and opportunities of this moment, we must take a deep historical dive, one that braids together the most crucial aspects of these three periods and the repeated clashes between the forces of redemption and the forces of reconstruction.

The First Reconstruction established a set of competing political norms and frameworks—reconstructionist and redemptionist—regarding Black citizenship, the virtues of Black dignity, and the future of American democracy. Reconstructionists fervently believed in a vision of multiracial democracy. Du Bois coined the term “abolition democracy” to describe what seemed to promise a second American founding, one where Black political, economic, and cultural power would give new meaning to citizenship, liberty, freedom, and democracy.

The left wing of the First Reconstruction era’s political spectrum, sometimes called Radical Republicans, believed in social equality as well as political rights. They sought economic justice and repair through the redistribution of land in hopes that this, alongside Black men’s suffrage, would provide a foundation for Black political power. Black leaders, such as the fugitive slave turned abolitionist journalist Frederick Douglass, sufficiently impressed Abraham Lincoln so much that the president came to believe that the most intelligent African Americans deserved voting rights. Lincoln and other moderate Republicans had initially hesitated on the matter of voting rights for Black folk. The Great Emancipator agonized Black peoples’ ability to fully integrate (both racially and otherwise) into the American political family. Slavery, and the anti- Black racism it created, planted the seeds of bipartisan doubt about the moral and political worthiness of Black people for full and unfettered citizenship, notwithstanding the fact that 200,000 Blacks had fought for the Union in the Civil War.

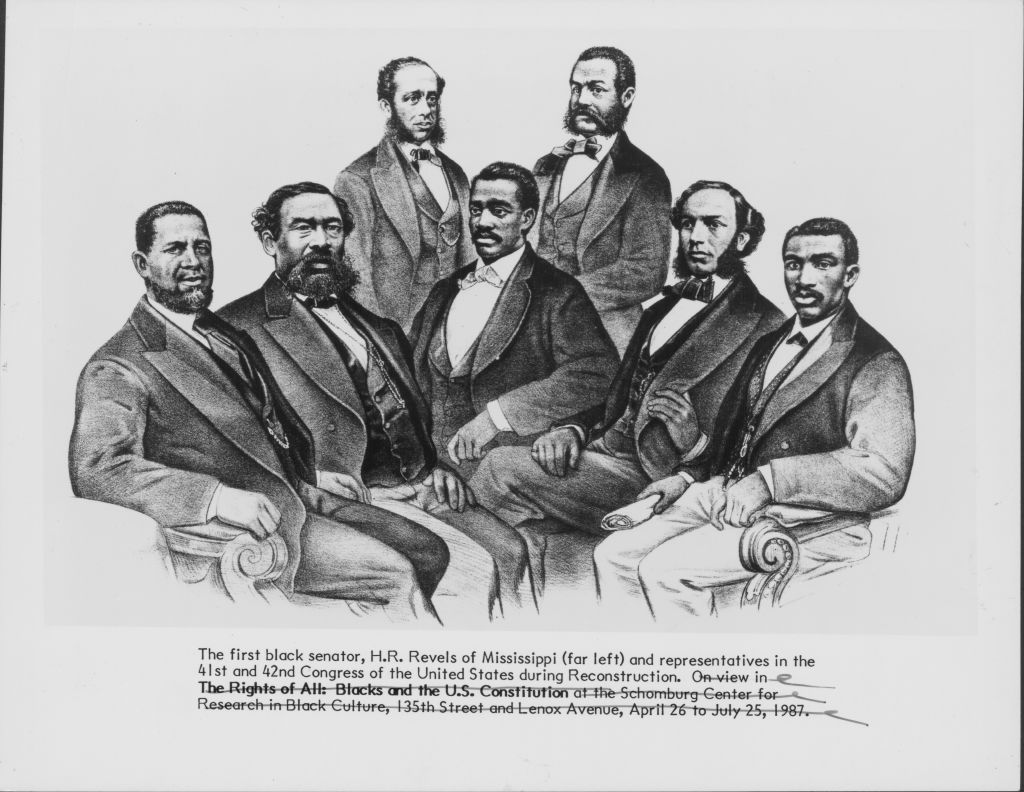

Reconstructionists deployed many strategies in their efforts to create a multiracial democracy in the post–Civil War years. They organized along religious, agricultural, political, economic, and civic lines, seeking to make good on federal promises of citizenship following ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. Over two thousand Black men held public office in the three decades after slavery at the local, state, and federal levels. Reconstructionists filed lawsuits against the imposition of racial segregation, passionately advocated for a new social compact for Black Americans and the rest of the nation, and challenged the onslaught of racial violence under Jim Crow with self-defense and paramilitary units, as well as through the creation of schools, churches, universities, farming co-operatives and mutual aid groups. Reconstructionists embraced America as a constantly changing political reality that could become a multiracial democracy through the collective will of people of conscience.

Redemptionists interpreted America’s political future through an entirely different set of experiences. From the ashes and ruins of Confederate rebels came a vow among white supremacists to “redeem” the South of “Negro domination” or perish. The Confederacy’s defeat compelled a change in strategy, but not an end to morally reprehensible tactics which redemptionists innovated during peace-time. No longer content to create a republic of slavery, they now endeavored to turn America into a Southern Nation. Racial terrorism accompanied political, legal, and legislative efforts to reestablish slavery by other means. Reconstructionists exhibited a passionate commitment to achieving the goal of multiracial democracy, but redemptionists matched their level of belief, and at times violently exceeded them, in their efforts to reestablish white supremacy.

Redemptionists sought to reinscribe slavery’s power relations between Blacks and whites via racial terror, through Black Codes that disenfranchised Black voters, and by ending federal protection for Black citizenship. They sought to allow former Confederates to hold political office, while denying Black voting rights. To reclaim their lost power, they perfected the use of organized terror, fraudulent election claims, and Black labor exploitation through contracts designed to compel permanent servitude. Like their reconstructionist counterparts, redemptionists deployed multiple strategies. Their goal proved to be the expansion of a racial caste system in peacetime thought to have been abolished through war. Their policy, legislative, and legal victories ensured that even the least privileged whites would amass more land and wealth; have greater access to jobs, health care, and the justice system; and achieve better outcomes than Blacks. They weaponized political, economic, judicial, and legislative strategies to make this happen. But racial violence proved to be the redemptionists’ main political tool, as many of them were ex‑Confederates well trained in the art of warfare.

Read More: America’s Long Overdue Awakening to Racial Injustice

Organized violence against prominent local Black people, including officeholders and other political leaders, ministers, and their families, made reconstructionist efforts to achieve dignity and citizenship both perilous and deadly. Redemptionists stymied Black progress toward economic independence through sharecropping and a debt peonage system that encumbered Black farmers with overwhelming financial burdens. These conditions often made it impossible for them to leave the plantations they had toiled upon under chattel slavery. The convict-lease system criminalized newly freed Black men, women, and children through vagrancy laws that gave the authorities permission to arrest African Americans for petty and quality‑of‑life crimes. An inability to pay cash bail, fines, and fees set thousands of Blacks down a dark road toward incarceration and personal ruin. Black inmates were then leased to private companies as laborers, and their wages were handed over to local municipalities, which thus extracted financial gains from organized racism. Redemptionists championed public policies that stripped Black voting and citizenship rights. Across the former Confederacy, states passed laws, adopted codes, and enacted policies that made it more difficult for Blacks to serve on juries, hold certain political offices, and exercise the ballot. In some cases, they were barred completely from engaging in these activities.

If some of this sounds familiar, it should. Contemporary voter suppression legislation represents one of redemptionism’s most stunning modern legacies. So, too, do mass incarceration, racial profiling, and racially exploitative prison labor. The racial violence directed against Blacks who tried to vote— or to swim at racially segregated beaches, eat at restaurants, travel on buses and trains, or stay at hotels or motels— during the twentieth century contained a direct throughline to this redemptionist vision of America.

Yet America’s historical memory quickly forgot slavery’s violence, war’s pestilence, and the cowardice of white supremacy in favor of a new story, one rooted in efforts at national reconciliation at the expense of Black dignity and through the denial of Black citizenship. On May 1, 1865, in Charleston, South Carolina, Black Americans organized the first Memorial Day (then called Decoration Day) to honor the 257 Union soldiers buried in unmarked graves inside a former horse- racing track turned Confederate prison. Thousands of Black men, women, and children engaged that day in rituals of memorialization for those who had sacrificed their lives to bring about a new birth of American freedom. By the end of the nineteenth century, Memorial Day parades, celebrations, and commemorations were being held in virtually every part of the nation. Yet the meaning behind these celebrations turned the catastrophe of a war fought over slavery into an altar of national unity, with Union and Confederate veterans alike proclaiming the war as an unfortunate misunderstanding, where both sides fought honorably. If racial slavery had produced the chasm of war, it would take the stripping of Black citizenship to broker a new national peace.

Redemptionists identified themselves as heroic defenders of a misunderstood South. In their telling, it was the South that was under assault, and it was their duty to keep power out of the hands of impudent Blacks, who they said were unprepared to perform the duties of citizenship in an intelligent manner, let alone serve as competent legislators. But redemptionists also prefigured contemporary racial gaslighting. They were architects of racial oppression, but denied the existence of the edifices they built to stand in the way of Black citizenship. While they sometimes called openly for white supremacist rule as a bulwark against Black voting rights and citizenship, they simultaneously claimed that their righteous indignation had nothing to do with race. A version of white supremacy claiming to be color- blind began to take root during the First Reconstruction. Redemptionists normalized violent intransigence against Black citizenship by advancing the notion that African Americans, having been so recently uplifted from slavery, were simply not ready to assume the burdens of political power. Massacres of Black Americans took place in 1866 in New Orleans and Memphis, less than a year after passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, but the reasons for the massacres were never fully acknowledged, and many denied they even took place.

Redemptionism, over time, became the face of the Democratic Party, a situation that imperiled Black rights and the health of American democracy itself. As redemptionism’s star grew, so too did its political influence. Violent conflicts, legislative jockeying, and political debates pitting Democrats versus Republicans gave way to bipartisan accord between the major political parties on Black subjugation. Redemptionists successfully bound together a dishonorable political coalition that rationalized racial oppression on the color-blind model. By simply ignoring the Reconstruction-era constitutional amendments through a bipartisan lack of enforcement, redemptionism became the law of the land. Redemptionists turned white supremacy into a kind of civil religion and civic nationalism. They professed devotion to a Christian God unwilling to force them to submit to Black political domination. They committed wholescale atrocities in defense of an American Dream that they narrated as a divine gift to white folk. Redemptionism convinced white Americans living outside the South, including, but not limited to, Republicans, to collaborate in the shaping of a new national political order based on racial oppression.

Read More: How Reconstruction Still Shapes American Racism

In this way, redemption became a core feature of American exceptionalism. American exceptionalism portrays the Nation’s history as a kind of bedtime story, with a beginning, a middle, and a triumphantly happy ending. It glosses over deeply embedded themes, including the history of inequality, the history of economic injustice and settler colonialism, and the history of violence against women, Queer people, and Indigenous people, in favor of a narrative highlighting progressive change over time. It ignores the sad reality that a civil war was not sufficient enough a price to purchase Black citizenship and dignity. Instead, it views entrenched patterns of racial violence, Black deaths, and white supremacy as aberrations of an otherwise healthy body politic. Racial slavery, structural violence, systemic racism, and white supremacy are largely absent from this story. The focus is on reconciliation, triumph against evil, and a nation’s unbounded ambition for greatness under the beneficence of God himself (the Good Lord is always a He).

Du Bois called America “a land of poignant beauty, streaked with hate and blood and shame, where God was worshiped wildly, where human beings were bought and sold, and where even in the twentieth century men are burned alive,” and this unvarnished description continues to resonate deeply. America remains a nation divided by cruel juxtapositions between slavery and freedom, wealth and inequality, beauty and violence. Our history reminds us that the racial juxtapositions of the present are not aberrations; rather, they reflect an unhappy pattern from the past that continues into the present.

America’s Third Reconstruction offers the opportunity for democratic renewal that centers racial justice as the beating heart of a new civic nationalism capable of restoring our national honor. Building what Martin Luther King Jr. called the “Beloved Community” free of poverty, violence, and racism, is within the nation’s future grasp if it finds the courage to face its tragic past. Since the death of George Floyd in 2020 Americans have witnessed how a nation can come together after it comes perilously close to falling apart before the eyes of the world. From the call to reimagine public safety and transform systems of punishment into investments into vulnerable communities, to statues and memorial dedicated to white supremacy being replaced by emancipationist symbols of abolition-democracy, we have seen how quickly our circumstances can change. New political worlds are being created all around us.

Black dignity and citizenship comprise the essence of the moral and political project that represents the most substantive issue of our era. The citizenship Barack Obama projected to the world from the towering heights of American power required the dignity expressed by BLM from the lower frequencies of the nation’s hidden bowels. The backlash to this current project of reconstruction continues an unfortunate pattern, one that finds redemptionists, generation after generation, winning the narrative war that defines America’s tenuous political reality, shapes our professed moral compass, and guides our economic priorities. And so, in the face of a new Lost Cause peddling voter suppression, the criminalization of Black folk, and censorship efforts to limit the stories we share with a new generation, the work of reconstruction continues. America can finally shed the tragic history it has remained enthralled by for almost two centuries, or choose the path of multiracial democracy that can save the national soul. We have, just as we did during two earlier periods of reconstruction, a grave moral and political choice to make. I choose hope.

Adapted from Peniel E. Joseph’s new book The Third Reconstruction: America’s Struggle for Racial Justice in the Twenty-First Century

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com