The morning sky was dull gray with low-hanging clouds over the battleship on which the war that began with the attack on Pearl Harbor more than a thousand days before ended with Japan’s formal surrender on September 2, 1945. The highest-ranked military leaders of the victorious Allied nations, along with representatives of the defeated Empire of Japan, were standing in designated spots on the teak deck of the U.S.S. Missouri. In the superstructure rising high above, every level and catwalk was filled with hundreds of white-capped sailors gawking at the scene below.

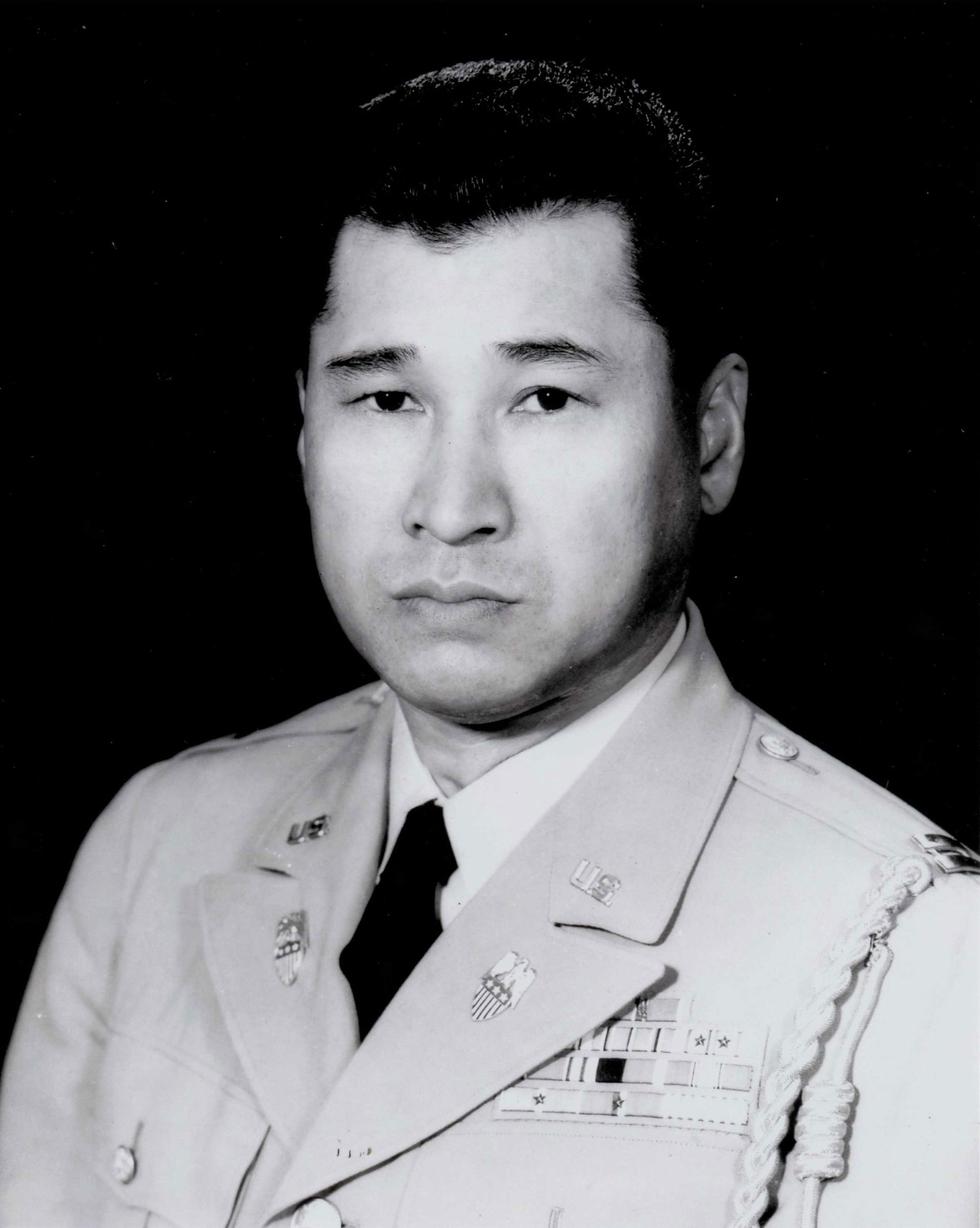

Standing nearby on a subdeck to observe the ceremony with a group of U.S. news correspondents was their official interpreter, Thomas Sakamoto, 27, of San Jose, Calif., a tall Japanese American who was one of the Army’s newest second lieutenants in the Pacific.

When General Douglas MacArthur stepped from a sea cabin, he strode stiffly to a cluster of microphones, and read a short statement. He then invited the representatives of Japan and the Allies to sign the surrender document.

Sakamoto was honored to be a witness to such history, something he appreciated even more when he learned he was one of only three Japanese American servicemen aboard Missouri that morning. A decade earlier, he had attended a boarding high school in Japan, where his immigrant parents who settled in California sent him to learn about their homeland. He was proud of his lineage, but during his stay in Japan he was a student of the culture, not a convert. He did not have divided loyalties. He was an American by birth and upbringing, and Japanese by ancestry. All of which had made Tom Sakamoto— and thousands of other Japanese American soldiers—invaluable to the U.S. Army’s Military Intelligence Service in the war against Japan.

The journey that brought him to Missouri that morning began a month before Pearl Harbor in 1941, when Sakamoto reported with 57 other Japanese American enlistees and draftees to a new Army language school in San Francisco. Nearly all of them had spent at least a few years attending school in Japan, and were fluent in the language. A small cadre of military intelligence officers who had been stationed in Japan in the 1930s had sounded the alarm in Washington that summer as tensions worsened between the two countries that there would be enormous language difficulties in the event of war with Japan. They argued that few westerners had a mastery of the complex Japanese language. By the time the first class graduated six months later, the war with Japan was raging.

Most of the graduates headed directly to the Pacific, and were among the very first Nisei soldiers to see combat in World War II. The top ten students—including Sakamoto—were retained to teach at the Army’s expanded Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) in Minnesota. A year later, Sakamoto was ordered to the Pacific as head of a 10-man Nisei team attached to the 1st Cavalry Division for the invasion of the Admiralty Islands, where they translated a cache of Japanese documents revealing crucial details of an enemy attack which was beaten back, saving American lives.

By the war’s end, MISLS had graduated 6,000 Japanese-language interpreters, translators, and interrogators. They served throughout the Pacific. In the tropical jungles of New Guinea. The bloody beaches of Iwo Jima. The steamy mountains of Burma with the storied Merrill’s Marauders. The caves of Okinawa. Tantamount to a secret weapon in the war against Japan, these young men ached for a chance to demonstrate their loyalty to America—even in the face of the racism and xenophobia that had become so inflamed after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and even as their families were rounded up and sent to internment camps. In effect, they were fighting two wars simultaneously; one, against their ancestral homeland; the other, against racial prejudice at home.

And yet, the story of their service is little known, even today. While the exploits of the all-Nisei infantry units fighting the Germans in North Africa and Europe received widespread recognition during and after the war—portrayed in countless books and films—the fact that U.S. combat units fighting in the Pacific had Nisei teams that understood the Japanese, read their communications, and interrogated POWs, was among the best kept secrets of the war. Afterwards, a veil of secrecy stayed in place over matters pertaining to military intelligence, and even when World War II records started to be declassified decades later much of their story remained untouched at archives. Astonishingly, no roster of the Japanese Americans who served in the Pacific was ever compiled by the Army. Many Nisei vets of the Pacific, satisfied with having done their duty and proven their loyalty to the U.S., did not speak of their wartime experiences for years—or ever—even to their families.

Japanese Americans, with ancestral ties to a nation with which we were at war and distrusted for that reason by many of their fellow Americans, became huge assets to the U.S. military because they knew the enemy better than anyone and were highly motivated to defeat them. In an America that too often prejudges people based on race and ethnicity and countries of origin, their timeless message of courage and patriotism should not be forgotten.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com