At some point things were destined to settle down in the glassed-in mission control room at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Md. For much of this year, the Institute has been the center of the astronomical world. After all, it is there that each image captured by the new James Webb Space Telescope first arrives, including the dazzling batch received and released in July. But the real work the Institute team does—analyzing the scientific data embedded in the pictures— is quieter, less flashy stuff.

Still, this week, as NASA reports, that quiet was broken by a new analysis of one of the July images. And, as TIME has just learned, Webb will stir even more excitement soon with a much-anticipated first-of-its-kind photo release. Together, the STScI team’s continued photo analysis will tell us more than ever about solar systems beyond our own—and the possibility that life could exist there.

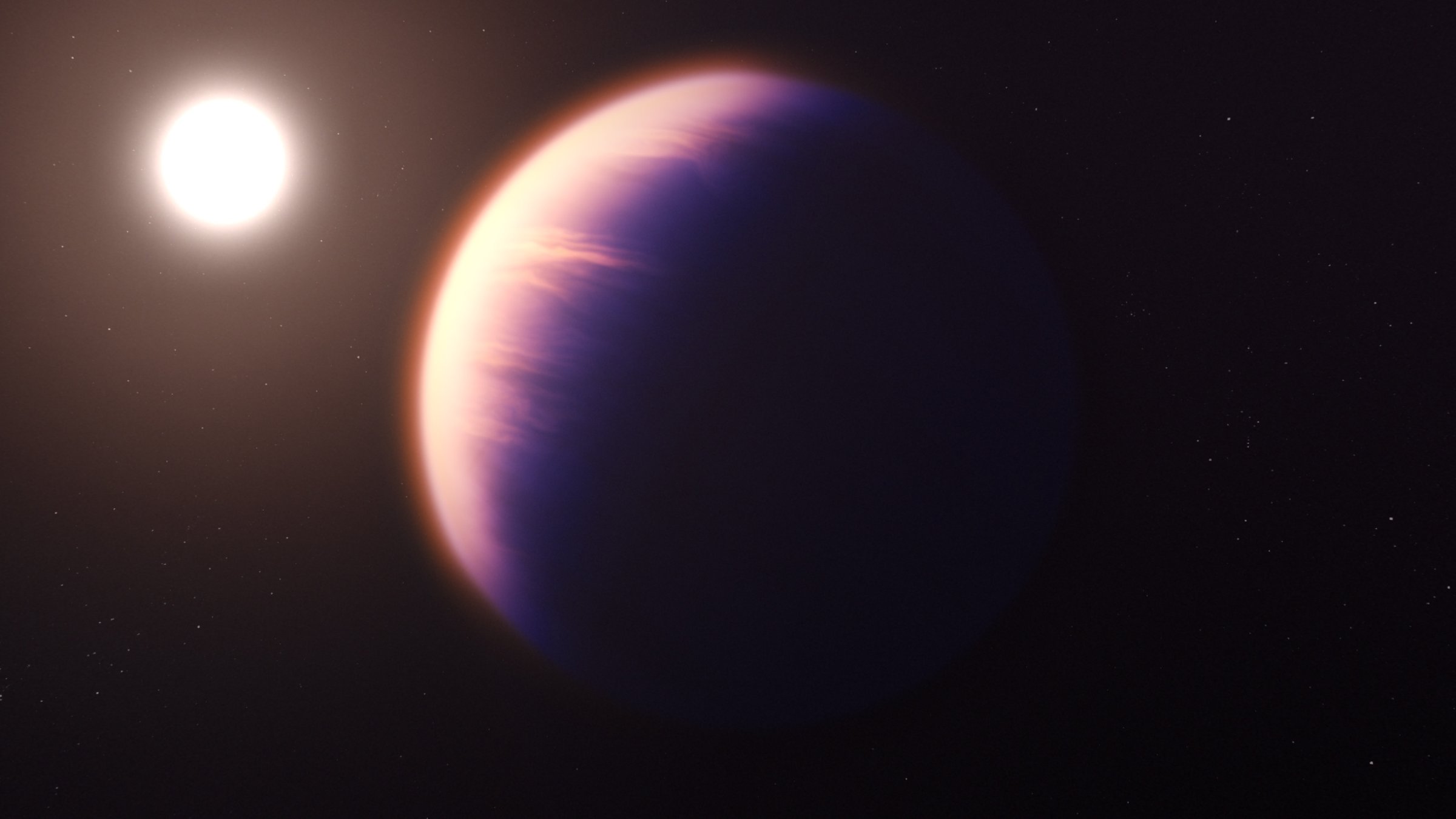

To begin, this week STScI researchers announced that Webb had taken a big step in its search for biology’s chemical fingerprints on distant exoplanets (planets orbiting other stars): the discovery of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of a planet known as WASP-39 b. It marks the first clear detection of CO2 in the atmosphere of any planet outside of the eight that circle our own sun.

WASP-39 b is what astronomers rather unscientifically refer to as a puffy planet, with a diameter 1.3 times that of Jupiter but a mass only one quarter as great. It also orbits so close to its parent star that its atmosphere reaches a broiling 900º C (1,600º F). The presence of organic chemistry notwithstanding, WASP-39 b is thus not the kind of place astronomers would expect to go looking for life. Still the presence of CO2 on the planet, combined with water vapor, sodium and potassium that the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes had already discovered there, is one more bit of proof that the universe is, among other things, a giant organic chemistry set, one in which the stuff of biology is found pretty much anywhere. That holds promise for similar discoveries on rockier, more temperate worlds, where life could take hold.

“Detecting such a clear signal of carbon dioxide on WASP-39 b bodes well for the detection of atmospheres on smaller, terrestrial-sized planets,” said astronomer Natalie Batalha, of the University of California at Santa Cruz, who leads the team that made the discovery, in a statement. With more than 5,000 exoplanets having been spotted throughout the galaxy, astronomers now believe that virtually every star in the universe is circled by at least one planet—and many, like our own sun, by a whole litter of them. That’s a lot of places for biology to take hold.

Meantime, expect bigger news from Webb in the coming weeks—and a lot more hoopla descending on the STScI mission control. While astronomers have been able to study the atmosphere of exoplanets by analyzing the changes in the wavelength of light that streams through the air of the planet as it passes in front of its parent star, no one has ever captured a picture of an exoplanet itself. That, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson told TIME in a conversation last week, is about to change, thanks to Webb.

“Just a sneak preview,” he said, “the next photo you’re going to get [from Webb] is of an exoplanet. I don’t know when they’re coming out with it and I haven’t seen it yet. But…it’s just opening up all new understanding of the universe to us.”

This story originally appeared in TIME Space, our weekly newsletter covering all things space. You can sign up here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Introducing the 2025 Closers

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com