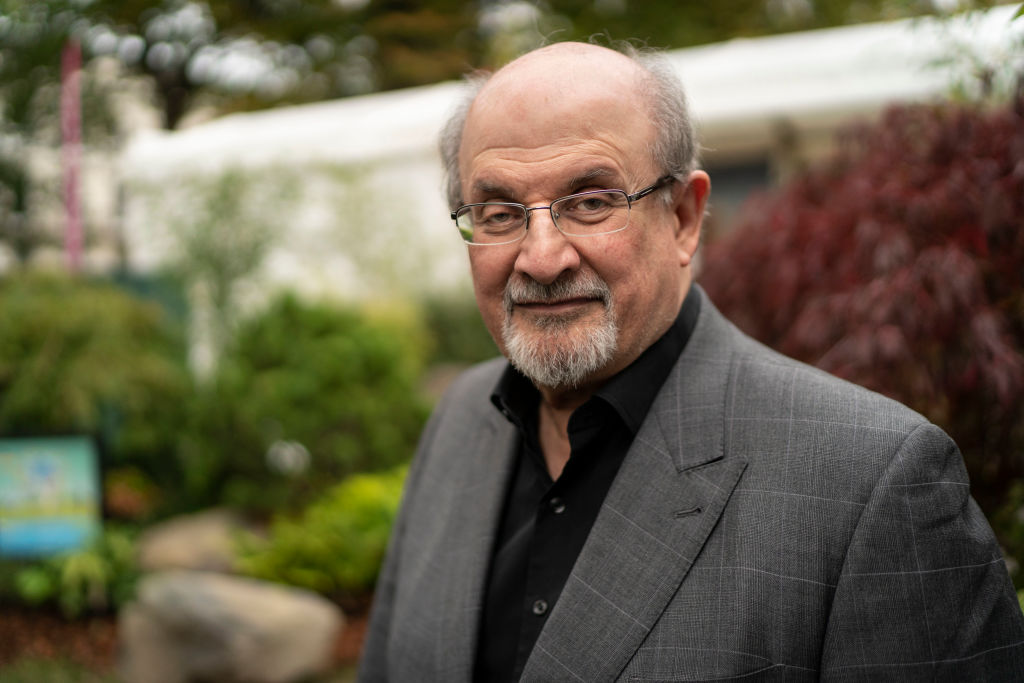

Salman Rushdie, the Booker Prize-winning author of globally acclaimed books including Midnight’s Children and The Satanic Verses, was attacked on Friday morning at an event in New York state. On Friday evening, his agent, Andrew Wylie, told the New York Times that Rushdie was on a ventilator and unable to speak. Though the attacker’s motive is not yet known, the incident marks the latest in a series of threats against Rushdie’s life and ideas, beginning with controversy surrounding the publication of The Satanic Verses in 1988.

What happened to Salman Rushdie?

On Friday morning, at around 11 a.m., a male suspect attacked Rushdie, 75, and interviewer Henry Reese, according to New York state police. Rushdie was speaking at a lecture series in the 4,000-seat amphitheater of Chautauqua Institution, a nonprofit education center and summer resort in western New York, roughly 400 miles from New York City.

In a statement, the New York state police said that Rushdie suffered an apparent stab wound to the neck, while Reese suffered a minor injury. Late Friday afternoon, Major Eugene Staniszewski said at a press conference that a doctor in the audience immediately started first aid for Rushdie. He was then transported by helicopter to a nearby hospital.

Rushie’s agent, Andrew Wylie, told the New York Times on Friday afternoon that he was undergoing surgery. Later on, told the newspaper in an email that “The news is not good” and that “Salman will likely lose one eye; the nerves in his arm were severed; and his liver was stabbed and damaged.”

Trooper James O’Callaghan said at the press conference that there was not yet any indication of motive. Also at the press conference, officials said they were still working to get search warrants, but identified the man taken into custody as Hadi Matar from Fairview, New Jersey.

Brad Fisher, a retired advertising writer, was in attendance at the event. He had just taken his seat and Reese was making introductory remarks when a man ran up onto the stage and started pounding Mr. Rushdie in the chest with rapid strokes, Fisher said.

“I didn’t understand what I was seeing when this man started attacking—it was one of those things you don’t process,” Fisher said. “And then when I realized what was going on, it was shock and disbelief and all those things that people experience when they see a tragedy live.”

From where Fisher was sitting, about 20 rows back from the stage, he couldn’t tell whether the attacker was holding a knife. When Rushdie fell to the stage, Fisher said, people began swarming around him and subdued the attacker. At least two uniformed security officers showed up “very quickly,” Fisher said.

Fisher has been attending events at the Chautauqua Institution since 1984, he said. As the Institution nears its 150th anniversary, Fisher pointed out that “it’s always been safe, always been open, and always been accepting.”

“So today, we’re not just mourning Mr. Rushdie’s tragic attack, we’re also mourning a sad change in that open and freewheeling environment,” Fisher said. “I don’t think this place is going to be the same after this.”

Rushdie’s literary legacy

Rushdie, an Indian-born writer, was speaking at Chautauqua Institution as part of its summer programming. The theme of the week in which Rushdie was scheduled to speak revolved around redefining the concept of “home.”

Born in Mumbai into an Indian Kashmiri Muslim family, Rushdie moved to England for high school and later permanently settled there. He is known for his novels, particularly 1988’s The Satanic Verses, inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

In 1989, following the publication of The Satanic Verses, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of Iran, issued a fatwa—a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law—calling for his assassination. The British government subsequently put Rushdie under police protection.

Rushie has long had an outsize footprint in the literary world. His second novel, Midnight’s Children, won the Booker Prize in 1981, and in 2007, he was knighted for his contributions to literature. He also served as the president of PEN America Center, which defends and celebrates the freedom of expression, from 2004 to 2006 and founded the PEN World Voices Festival.

“We can think of no comparable incident of a public violent attack on a literary writer on American soil,” Suzanne Nossel, the CEO of PEN America, said in a statement. “Just hours before the attack, on Friday morning, Salman had emailed me to help with placements for Ukrainian writers in need of safe refuge from the grave perils they face.”

The controversy over The Satanic Verses

The publication of The Satanic Verses, his fourth novel, met with immediate protests from Muslims over its portrayal of the prophet Muhammad. In the book, Muhammad (referred to as Mahound) adds three disputed verses to the Quran, which the narrator says came from the Archangel Gabriel. The book was banned in 13 largely Muslim countries, and Iranian state media renewed the fatwa with a $600,000 bounty on the author’s head in 2016. It was also the subject of a massive and deadly protest in Pakistan. Rushdie survived a failed assassination attempt in 1989 and was included on an Al-Qaeda hit list in 2010.

As the fatwa also called for the deaths of people involved with the book’s publication, and Rushdie himself was for many years in hiding, several people connected to the novel—including its Norwegian publisher, Japanese translator, Italian translator, and Turkish translator—were victims of apparent assassination attempts in the early 1990s. The Japanese translator, Hitoshi Igarashi, succumbed to his injuries, and dozens were killed in a fire resulting from the attempt on the life of Aziz Nesin, the Turkish translator.

“Salman Rushdie has been targeted for his words for decades but has never flinched nor faltered,” Nossel said. “He has devoted tireless energy to assisting others who are vulnerable and menaced.”

“While we do not know the origins or motives of this attack,” she continued, “all those around the world who have met words with violence or called for the same are culpable for legitimizing this assault on a writer while he was engaged in his essential work of connecting to readers.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com