Kenya heads to the polls Tuesday to select the country’s new president amid soaring food and fuel prices, a crippling drought and, crucially, concerns over whether the vote will be free, fair and peaceful.

Concerns are particularly high over how the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission, which is in charge of running Kenya’s elections, manages the process. “They haven’t been anywhere near professional,” says Ken Opalo, an assistant professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service. This year will serve as the first major test for Kenya’s electoral system since the chaotic 2017 election.

Polls are open from 6 a.m. until 5 p.m. local time and the race remains too close to call. The electoral commission can take up to seven days to tabulate the votes. If no candidate wins an absolute majority, there will be a run-off vote, which has never happened before.

Who are the candidates running for President of Kenya?

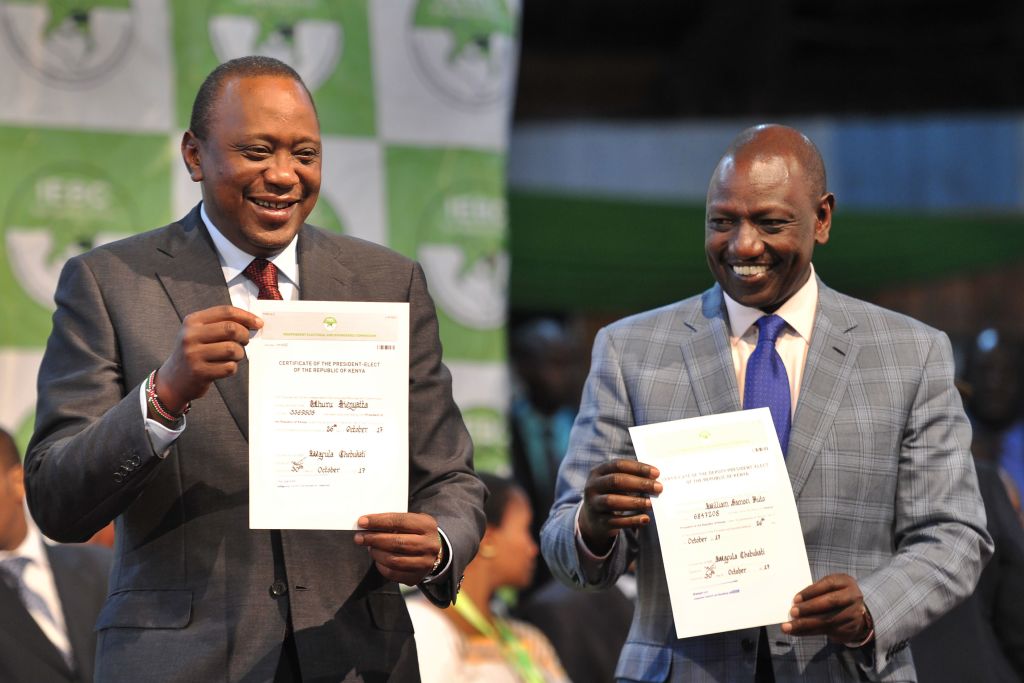

Four candidates are in the running, and the favorites are veteran opposition leader Raila Odinga, 77, and current Deputy President William Ruto, 55. President Uhuru Kenyatta, 60, cannot run for a third time because of term limits.

Odinga, of the center-left Orange Democratic Movement, is running for president for the fifth time and stated that this run will be his last. He is contesting under an uneasy Azimio La Umoja Alliance, which includes the right-wing Jubilee Party led by the current president. He is the son of the country’s first vice-president and served several years in prison as a political prisoner in the 1980s and early 1990s.

More from TIME

One of Odinga’s key policy proposals is a social welfare program in which he is promising to deliver 6,000 Kenyan shillings ($50) a month to the nation’s neediest households. It would significantly increase the amount of cash assistance given to families through an existing welfare program. He has also promised to set up universal health care through a program called Babacare.

Ruto, of the center-right United Democratic Alliance, has attempted to portray himself during campaigns as on the side of the poor and youth, even coining the phrase “hustler nation”—a nod to his own humble beginnings as a chicken seller as a teenager. He was an agriculture minister before becoming Deputy President in 2013 and is considered one of the nation’s largest maize farmers. He and Kenyatta were slapped with charges by the International Criminal Court related to post-election ethnic violence following the 2007 race, which were later dropped for both individuals. The ICC cited insufficient evidence but refused to acquit either Kenyatta and Ruto.

Ruto is focused in particular on expanding access to credit for the informal sector, which includes small- and medium-sized businesses that have been hardest hit by the economic crisis.

Other presidential candidates include the wild-card George Wajackoyah, a professor and lawyer, and David Mwaure Waihiga, also a lawyer. Wajackoyah, who was taken in by Hare Krishna worshipers after being homeless as a child, has sparked a debate over the legalization of marijuana—one of the policies he has been vocal about on the campaign trail. Waihiga is also an ordained reverend and has proposed cutting income tax by half.

What are the major issues at stake in Kenya’s election?

“Top of mind for Kenyans looking at these elections is the cost of living crisis,” says Fergus Kell, a research analyst who studies Kenya at Chatham House. “There’s a real squeeze on ordinary Kenyans,” he adds. In recent months, inflation has shot up to as high as 8.3% and the war in Ukraine has contributed to long lines at petrol stations and an increase in the cost of essential foods such as maize flour and cooking oil.

According to the U.N., Kenya is also dealing with its worst drought in more than four decades. That has wreaked havoc in particular on herding communities in terms of food insecurity and mortality.

Read More: How Kenya Copes with Thousands of Displaced Climate Migrants

For the most part, “issues in Kenya have remained constant over the last few elections and the party manifestos are almost the same: fight corruption, uplift people from poverty,” says Gilbert Khadiagala, a professor of international relations at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa. What often becomes a deciding factor is voter allegiance to their ethnic groups, he adds.

Neither Odinga nor Ruto belong to the nation’s largest ethnic group, Kikuyus, but both have selected a Kikuyu individual to be their potential Deputy President. Odinga has tapped Martha Karua, a former justice minister, as his running mate—and if she wins, she would also become Kenya’s first female Deputy President. Ruto, for his part, has targeted much of his campaigning efforts towards winning over the Kikuyus and has made headway, despite opposition from Kenyatta, who is part of the community. “Within Kenyatta’s ethnic base, Odinga is actually losing to Ruto but Kenyatta has been useful for Odinga in helping craft a national coalition,” says Georgetown’s Opalo. “Without Kenyatta’s support, Odinga would not have been able to build the broad national coalition that he’s been able to put together.”

Kenya’s history of turbulent elections

In 2017, Kenya’s initial election results—which saw Kenyatta win 54% to Odinga’s 45% in August— were nullified by the Supreme Court and a new vote was ordered because of irregularities in the process. (The court said the initial vote was “not conducted in accordance with the constitution.”) The voting system failed to electronically transmit results from every station in a timely manner. Lawyers for Odinga successfully argued this opened the door for potential vote tampering. (International monitors had said the election was fair.) Odinga boycotted the re-run in October, which saw Kenyatta gather 98% of that vote.

The 2017 election was also marred by allegations of police impunity. Human Rights Watch said on Aug. 1 that it feared the failure of Kenyan authorities to address past abuses by police could heighten the risk of impunity around this year’s election, particularly if the results are disputed. Following the 2017 elections, Human Rights Watch and other groups documented 104 killings by police and armed gangs, with most victims being supporters of the main opposition party at the time.

And in December 2007, after President Mwai Kibaki of the right-wing Party of National Unity was declared winner of that year’s presidential election against Odinga, a dispute over Kibaki’s reelection led to weeks of violence along ethnic lines. At least 1,000 people died and more than 300,000 fled their homes. The Kikuyu, of which Kibaki hails, were the initial targets of violence following voting irregularities and allegations of fraud. But reprisal killings, particularly in the Rift Valley, quickly followed. Kenya enacted a new constitution in 2010 in response to the 2007-2008 crisis, resulting in the subsequent decentralization of power through the creation of 47 local county governments.

Violence since the 2007 elections has appeared to be more localized and on a smaller scale, experts say.

The current President’s shifting loyalties

A unique factor of this presidential race is the current President’s tussle with his Deputy President Ruto and backing of opposition candidate Odinga.

“This is an epic election in the sense that the outgoing President has taken a stand against his Deputy President and supported an opposition candidate,” says Witwatersrand’s Khadiagala.

In 2018, Kenyatta and Odinga surprised the nation by reconciling in a moment Kenyans refer to as “the handshake”; they developed a relationship and worked together on the Building Bridges Initiative, which aims to expand the executive branch’s powers, among other measures. But Kenya’s Supreme Court in March declared that their proposed changes were illegal.

Their partnership was made possible by the fact that Kenyatta and Ruto’s erstwhile alliance was from the outset “sort of a marriage of convenience,” Kell says. They were both facing charges at the ICC related to the post-election violence of 2007-2008.

Tensions between Kenyatta and Ruto ratcheted up in recent years; the Deputy President hasn’t been sitting in some cabinet meetings, Kell says, and eventually split off from the Jubilee Party he formed with Kenyatta in 2013.

But whichever way Kenyans cast their ballots on Tuesday, this will be a vote involving several firsts. It’s the first time since the country began its transition in 1992 towards democracy that there are no leading Kikuyu candidates. And Kikuyu opinion remains divided on both frontrunners. “The results will have some significant ethnic concentration of votes towards the two leading candidates,” says Georgetown’s Opalo. “But that shouldn’t take away from the fact that this time around ethnicity has not been as front and center as it used to be.”

Kell agrees. “Personalities have come through in campaigning more so than ethnic identity,” he says.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Sanya Mansoor at sanya.mansoor@time.com