As the heat index topped 100 degrees in Johnson County on Saturday, dozens of canvassers fanned out over affluent suburbs to knock on strangers’ doors and talk about an emotional, fraught, and, in many cases, very personal issue: the Kansas constitution.

The state’s voters are being asked to amend its constitution to explicitly say that it does not contain a right to abortion. The ballot measure, which was first proposed in 2020, is intended to undo a 2019 Kansas Supreme Court ruling that found that right was implicitly part of the state’s governing document.

The Aug. 2 vote will mark the first time the issue of abortion has been on the ballot since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the federal constitutional right to an abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. It also represents a new frontier in the fight over abortion access: the battle over state constitutions. Rachel Sussman, the vice president of state policy and advocacy at Planned Parenthood, tells TIME that for the foreseeable future, access to abortion is going to play out “singularly” at the state level. “That is going to be amending state constitutions, pushing state statutory protections for abortion, and going to the ballot and bringing some of these issues directly to the public,” she says.

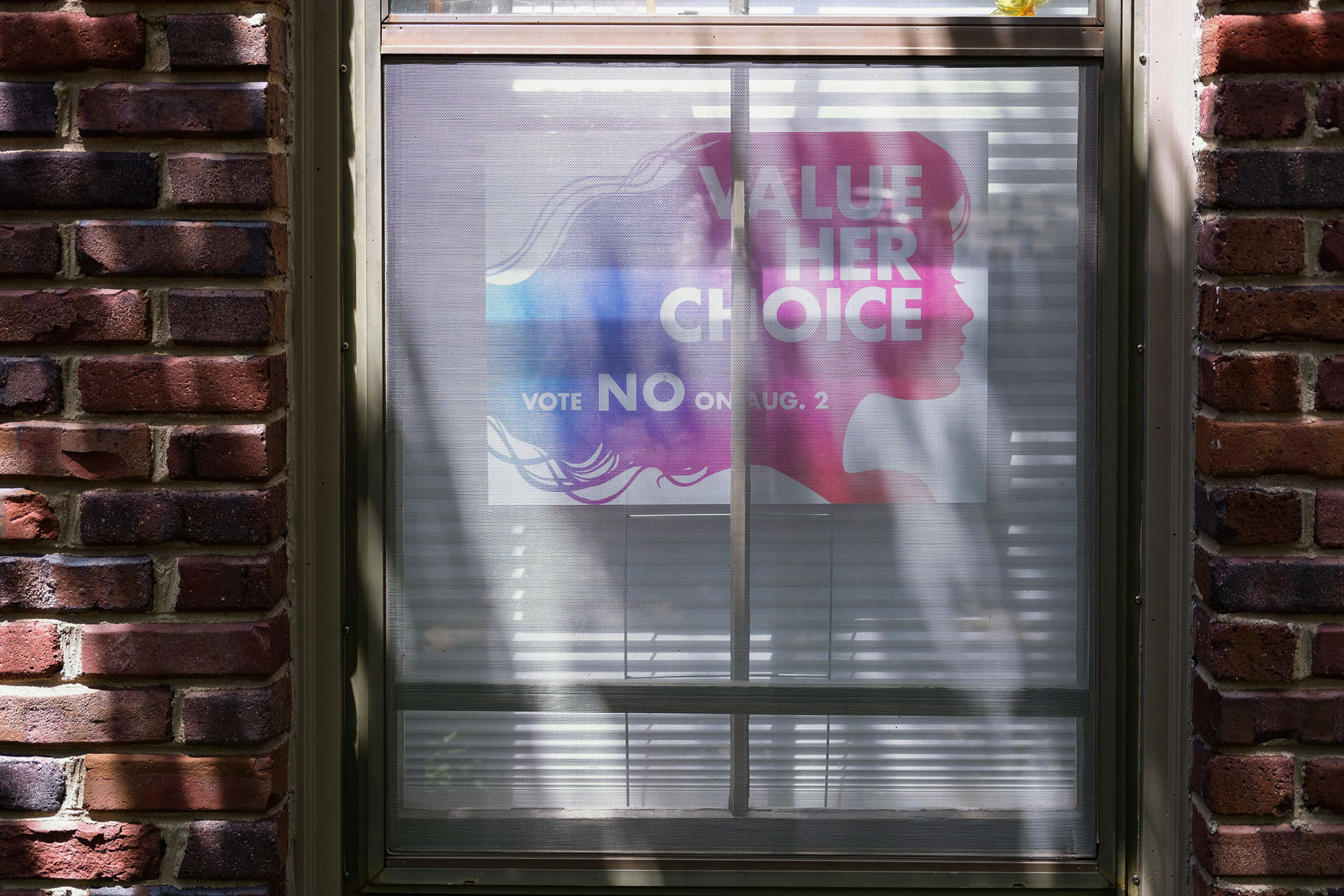

While canvassers with Students for Life of America—an anti-abortion group coordinating with the Value Them Both coalition supporting the amendment—were encouraging residents to vote for the ballot measure on Saturday, abortion rights canvassers with Kansans for Constitutional Freedom were urging its rejection. Both sides expect the Kansas race to be close: a statewide poll conducted by co/efficient this month found that 43% of Kansans said they plan to vote “no” while 47% said they plan to vote “yes.” Millions of dollars have poured into the race, with national abortion rights groups backing the “no” side and Catholic dioceses and churches funding efforts to vote “yes.”

While the campaigns were underway before Roe v. Wade fell, advocates on both sides tell TIME that the decision has given their efforts heightened urgency. On Saturday, 72-year-old Carolyn Sullivan told a canvasser she was voting “no” because she remembered a time before Roe and feared returning to it. “I’m Catholic. I’m not sure I could ever have an abortion myself. But that’s not the issue,” she said. “The government should not be telling me what I’m doing with my medical needs.”

That same afternoon, Joe Mayer, 78, told canvassers that his Catholic faith compelled him to vote “yes.” “Our church recommends we do that,” he said. “It is the right thing to do.”

Due to its location, loss of abortion access in Kansas would impact far more than just Kansans. With Roe gone, near-total abortion bans in neighboring states such as Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, and Texas went into effect, meaning more people than ever are now driving hours to reach the handful of abortion clinics in Kansas. On July 22, TIME spoke with five women who sought abortions at the Planned Parenthood Great Plains Comprehensive Health Center in Overland Park who said they had driven from other states to access the procedure. (Two came from nearby Missouri, whose residents have crossed the border for abortions for years because the state tightly restricted access even before the June decision.)

Cynthia, 31, who withheld her last name out concerns for her privacy, said she had driven five hours from Tulsa, Okla. to receive an abortion. A mother of two, the first of whom she had at age 18, she said she was in the process of building a business and did not feel prepared to have another child. She had not heard about the Kansas ballot measure, and was alarmed to hear its potential ramifications.

“Right now,” she said, “Kansas has been the hope for people like me.”

Ramifications across the Midwest

Kansas is a conservative state where registered Republicans greatly outnumber Democrats, and in presidential elections, voters strongly favor the GOP. But at the state level, its politics are more complex.

Democrats have been just as likely as Republicans to hold the governorship in recent decades and the majority of the current justices on the state Supreme Court were appointed by Democrats. Over the last 20 years, Republican state lawmakers have passed many restrictions on abortion, including a 24-hour waiting period, parental consent for minors, and strict limits on when private and public insurance can cover the procedure. But partly because of the 2019 court ruling, Kansas still allows abortions up to 22 weeks of pregnancy, making it an unlikely outpost of access in the Midwest.

More from TIME

Kansans’ views on abortion are nuanced, too. A 2021 survey from Fort Hays State University found that 31% of respondents viewed abortion as murder and 40% said they believed life began at conception. But more than 60% said they disagreed with abortion being completely illegal in Kansas and 51% said the Kansas government should not place any regulations on when women could get abortions.

Even before Roe fell, people from other states were coming to Kansas to get abortions. After the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, Kansas was one of the few states in the area that allowed clinics to remain open during lockdown. Then, in September 2021, Texas banned most abortions after around six weeks of pregnancy. Oklahoma enacted a similar bill in May 2022, and by the end of June, abortion was no longer a constitutionally protected right nationwide. Ashley Brink, the clinic director of the Trust Women abortion clinic in Wichita, says that starting with the Texas law last September, the number of out-of-state patients to her clinic doubled. In June, 172 of the clinic’s 272 patients seeking abortions were from out of state.

One 28-year-old woman, who declined to be identified out of concern for her privacy, said she had driven from Tulsa, Okla. to terminate her pregnancy at the clinic in Overland Park. She said her doctor told her she needed to because she could not get her stomach and thyroid cancer properly treated while pregnant. In her home state, abortion is now banned except for instances rape, incest, and “medical emergency” in which abortion is necessary to save the pregnant person’s life. She told TIME that her condition did not allow her to access the procedure there, and she couldn’t get an appointment at the closer clinic in Wichita.

Republican state Rep. Susan Humphries, who supports the amendment, describes the state’s current role in the country’s abortion post-Roe landscape as “an anathema to the citizens of Kansas, that we would be a destination for abortion.” Jaylem Durosseau, a strategic partnerships advisor with Students for Life of America, says that the influx of out-of-state patients has raised the stakes for the ballot measure, and his canvassers are excited about the possibility of making an even larger impact on limiting abortions.

The epicenter of the fight

In many ways, abortion rights advocates are heading into the Kansas ballot measure vote at a disadvantage. The Aug. 2 vote coincides with the state’s Republican and Democratic primaries, where Republicans typically show up in larger numbers.

“Republicans start out as the heavy favorites in any election on the primary ballot,” says Neal Allen, a political science professor at Wichita State University. “A primary in the first weekend in August is the worst time to get strong voter turnout. You have many people who are on vacation, students are not in school … and Kansas, like many states, has made it more difficult to register voters.”

Turnout in Kansas primaries has historically been about half as high as general elections. More Republicans tend to participate in primaries, as they more frequently have contested races. Kansans must be registered with a party to vote in a partisan primary, meaning the large share of voters who are unaffiliated are likely not used to voting in primaries and may not even know they can vote for the ballot measure. The state’s voters are 44% Republican, 26% Democratic and 29% unaffiliated.

Abortion has been a major issue in Kansas politics for years, and many Kansans already have firm beliefs on the issue. So advocacy groups are more focused on turning out their voters than changing minds. KCF has raised $6.54 million since the beginning of the year, with help from national groups like Planned Parenthood, the ACLU and the progressive Sixteen Thirty Fund, while the Value Them Both Association has raised $4.69 million, largely from the Archdiocese of Kansas City, the Catholic Diocese of Wichita and other religious groups. The overturning of Roe has supercharged efforts on both sides. Voter registration surged 1,000% on June 24, the day of the ruling. KCF says they raised almost $100,000 that day and went from 50 volunteer canvassers per week to 500 volunteers the week after, while Students for Life of America says their volunteers in the state have more than doubled since May, when a leaked draft opinion signaled the decision to come.

As with many elections, the race could be determined in the suburbs. Both sides are particularly focused on Johnson County, which is just southwest of Kansas City and the most populous in Kansas. Joe Biden won Johnson County in 2020 by 8 points, even as Donald Trump won the whole state by 14.

In their messaging, the campaigns are each trying to frame the ballot measure as a way to let voters decide the future of abortion in the state. The anti-abortion advocates in favor of the amendment say they merely want to reverse the state Supreme Court’s decision while abortion rights groups argue the amendment would open the door for state lawmakers to completely ban abortion. Democratic pollster Celinda Lake says her data shows that independent and even some Republican women voters are motivated by the idea of lawmakers “going too far.”

While Republicans in Kansas have publicly refrained from sharing their plans if the amendment passes, the Kansas Reflector published leaked audio on July 15 of state sen. Mark Steffen, a Republican, who said that if the amendment passed, the state legislature would be able to pass new laws “with my goal of life starting at conception.” (The senator did not respond to a request for comment.)

Similar fights are now set to play out around the country. Without a federal right to abortion, the procedure’s legality rests on each state’s varied political landscape. In places like Kansas, Montana, and Florida, where state courts have previously ruled the state constitutions protect the right to abortion, abortion rights supporters have found themselves defending those decisions from anti-abortion advocates who want to reverse the rulings or amend the documents. In other states, including Michigan, Vermont, and California, abortion rights supporters have launched proactive campaigns to enshrine the right in the state’s constitution. Before Roe was overturned, four states approved ballot measures like the one in Kansas and state courts had established state constitutional protections in a handful of other places, but in most states, there’s no definitive ruling on what the state constitution means for abortion, says Elisabeth Smith, director of state policy and advocacy at the Center for Reproductive Rights. “Until there’s a determination from the state supreme court,” she says, “it is an open question.”

A preview of what’s to come

In the new post-Roe landscape, advocates see the need for a “layered” fight, says J.J. Straight, deputy director of the ACLU’s liberty division, looking for ways to bolster abortion access through state houses, governors’ mansions, state constitutions, and state supreme courts.

In Michigan, Planned Parenthood and Gov. Gretchen Whitmer have each challenged the state’s 91-year-old abortion ban in court seeking to establish a state constitutional right to abortion. But after the Supreme Court overturned Roe, the campaign for a ballot measure to enshrine the right to abortion in the state’s constitution saw a massive surge in signatures. “These efforts are crucial to the fight for protecting access to abortion moving forward,” says Sussman of Planned Parenthood. “There needs to be more of them, and over time, a thoughtful and strategic nationwide effort to use state constitutions and ballot efforts to protect access.”

In some states, including Michigan and Kansas, these fights will also involve the elections for the state supreme courts. Conservative groups have historically spent significantly more on state supreme court elections than liberals have, and the 2019-2020 cycle was the most expensive cycle yet, according to a report from the Brennan Center for Justice. State supreme court elections also haven’t typically received as much attention as other statewide races, says Douglas Keith, counsel at the Brennan Center and co-author of the report. But the courts’ role in redistricting, voting rights, and now abortion, is changing that, with liberal groups looking to engage in court fights in North Carolina, Ohio, Montana, Michigan and Kansas. “What’s different now is that the U.S. Supreme Court is signaling a general withdrawal from the court’s role of protecting rights,” Keith says. “It’s clear that this is not just one issue that the state supreme courts are going to play a prominent role in. They may in fact become the primary venue for protecting individual rights.”

In Kansas, six of the state’s seven supreme court justices are up for retention elections in November, including three who were on the court for the 2019 abortion decision. So far, local groups on both sides of the abortion debate are focusing their energies on the ballot measure rather than the court races. But Kansas has seen intense battles over its Supreme Court justices in the past, and if the constitutional amendment fails, the Court will maintain a crucial role in deciding the future of abortion policy in the state. “I would be surprised if there was not a significant effort to unseat justices in this year’s retention election,” says Keith.

In the meantime, the future of abortion access hangs in limbo in Kansas, as well as for millions of people in neighboring states. Brenna Keener, 24, drove to the Overland Park clinic last week from Blue Springs, Mo. She described a brutal year that involved four surgeries to treat her Crohn’s disease. When she found out she was pregnant, she felt her body could not handle a pregnancy and she was not in a position to care for a baby on her own. With abortion almost completely banned in her home state, she drove to Kansas. She’s closely watching the ballot measure race, apprehensive that it might pass.

“Where was I going to go? I didn’t have anyone … I can’t emotionally, physically, and financially take care of anyone but me right now,” she said. “I could not imagine this not being an option for women at all.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Madeleine Carlisle/Overland Park, KS at madeleine.carlisle@time.com and Abigail Abrams at abigail.abrams@time.com