This week, NASA revealed for the first time five pictures taken by the James Webb Space Telescope. Together, these images—from the birth of stars to one of the deepest looks into the far reaches of space—offer some of the most detailed glimpses into the beginnings of our universe ever seen.

Here’s what each image shows and why it helps us better understand space:

SMACS 0723

Webb’s cameras can look deep into space and far into the past. Webb has the capacity to look 13.6 billion light years distant—which will be the farthest we’ve ever seen into space. This image of the galactic cluster known as SMACS 0723 contains thousands of galaxies, some of which are as far away as 13.1 billion light years. (A single light year is just under 6 trillion miles.) Since light takes a long time to travel so far, we are seeing the galaxies not as they look today, but as they looked 13.1 billion years ago. The bluer galaxies are more mature ones, containing many stars and little dust. The redder galaxies contain more dust, from which stars are still forming.

Carina Nebula

Stars, like the rest of us, are born, age, and die, and the Carina Nebula, located 7,600 light years from Earth, is one of the cosmos’s great stellar nurseries. The formations that look like cliffs are vast peaks of dust and gas, some as tall as seven light years. The Hubble Space Telescope has imaged Carina before, but never in the dazzling detail Webb has provided. Young stars are being born in this turbulent region, coalescing out of the surrounding material. As the stars form, they give off enormous amounts of energy that help give the overall nebula its shape. Red dots in the image are jets of energy being emitted by the growing, infant stars.

Stephan’s Quintet

Webb captured the greatest image ever taken of Stephan’s Quintet, a cluster of five galaxies, first seen by astronomers in 1877. The quintet is actually more of a quartet, with the leftmost galaxy located in the foreground, 40 million light years from Earth, while the other four are located a far more distant 290 million light years away. The four closely packed galaxies interact, with dust and stars gravitationally pulled from one to another—commingling their material. Clusters of young stars appear as bright sparkles in the image and thousands of more-distant galaxies are visible in the background.

Southern Ring Nebula

A dying star can be a surprisingly beautiful thing—and two such stars can be twice as striking. Webb captured an image of this pair of elderly stars orbiting each other approximately 2,500 light years from Earth. As the stars enter the end of their lives, they give off gas and dust that form the nebulae, or clouds, that surround them. Webb has the capability not just to image the Southern Ring Nebula, but to analyze its chemistry, understanding more about how stars shed their matter as they die. The brighter of the two stars is younger than the other and has yet to emit as much material. As the stars orbit each other they effectively stir the gaseous nebula, giving it its signature shape.

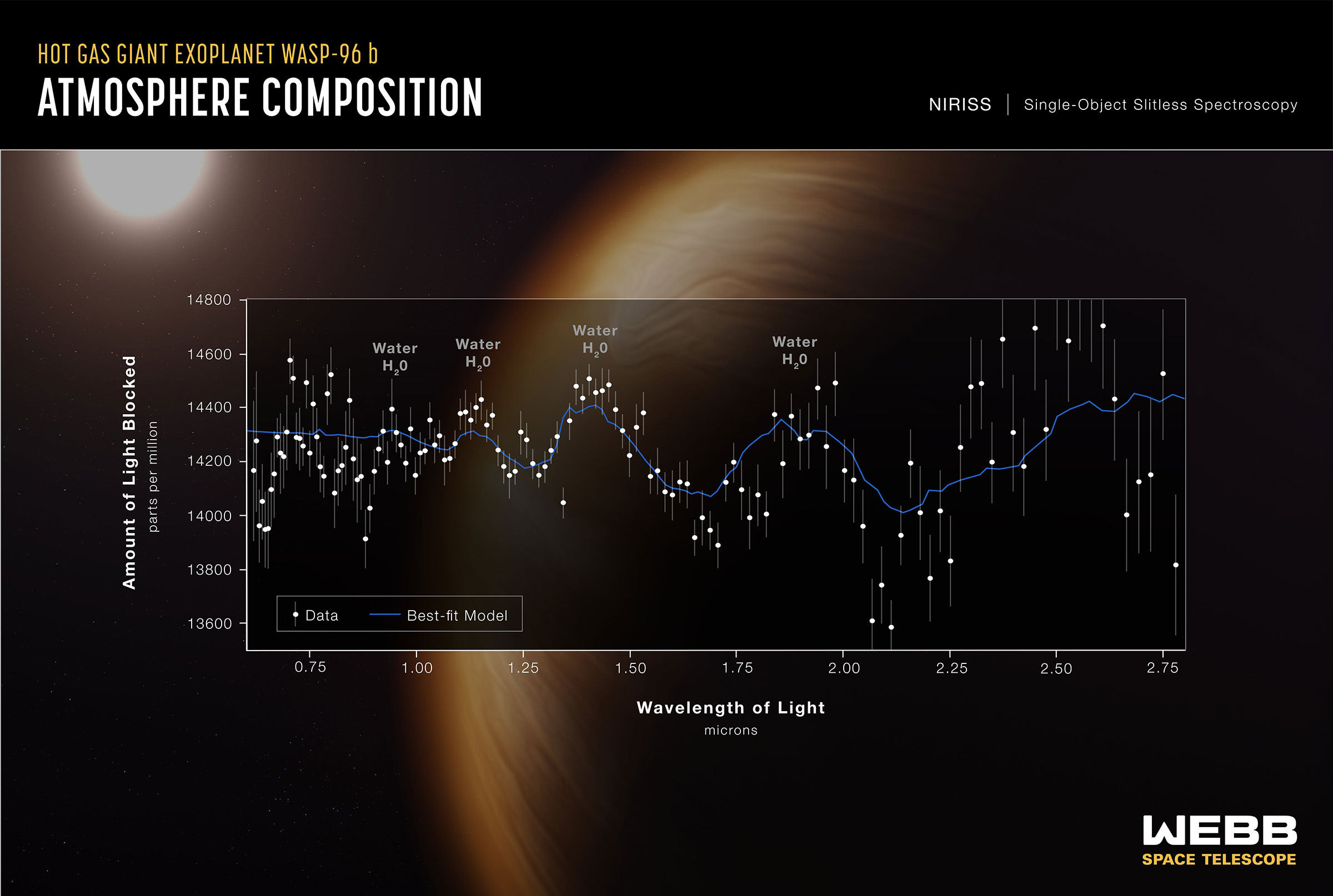

WASP 96 b

A scientific graph is not nearly as striking as a cosmic photo, but in this case the graph has a story to tell. Webb is studying exoplanets—or planets that orbit other stars—particularly the make-up of their atmospheres. As the planet passes in front of its parent star, Webb can analyze the starlight streaming through the atmosphere, looking for the chemical fingerprints of biology. In this graph, Webb analyzed the atmosphere of WASP 96 B, a Jupiter-like planet that lies 1,150 light years from Earth. Webb did not find biology, but as the graph shows, it did find plenty of water in the planet’s clouds—and water is the key ingredient for life as we know it.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Your Vote Is Safe

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- The Surprising Health Benefits of Pain

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com