Virgil Abloh knew how to get people talking. In 2012, when he launched his first fashion brand, Pyrex Vision, Abloh bought deadstock flannel shirts from Ralph Lauren for $40 a piece, screen printed them with the word “Pyrex” and the number 23 (an homage to Michael Jordan), priced them at $550—and sold out his stock in minutes. The shirts became an instant lightning rod, setting the internet ablaze with debates about design ethics, streetwear’s bootlegging tendencies, and the profitability of hype—and making Abloh a figure of major interest in fashion.

For Abloh, the controversy was part of the point. For the 2016 runway show for Off-White, Abloh’s cult brand, the designer enlisted graffiti artist Jim Joe to emblazon a rug with a quote from a menswear blog about the infamous Pyrex shirts: “It’s highly possible Pyrex simply bought a bunch of Rugby flannels, at retail no less, slapped ‘PYREX 23’ on the back and re-sold them for an astonishing markup of about 700%.” Brandishing the quote was a fitting metaphor for Abloh’s design philosophy, in which he contended that everything, even dissent from the haters, was an opportunity to create. The late Ghanian American designer, who died at age 41 in November 2021 from cardiac angiosarcoma, a rare form of cancer, was always less concerned with past critiques than he was with making something new. The rug from that early show is now prominently displayed in the Brooklyn Museum as a part of Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech,” a new exhibit, opening on July 1, that bears witness to the dizzying expanse of Abloh’s work and creativity, from his early creations through the designs he produced as the artistic director of menswear at Louis Vuitton.

During his lifetime, Abloh wore many hats: fashion designer, artist, DJ, civil engineer. He refused to limit his work to a singular medium or genre, famously rejecting labels like designer or artist, and instead preferring to describe himself simply as a “maker.” For Abloh, creation was about re-imagining the possibilities of what something could be, bridging the gaps between high and low, between the institutional and the underground. In his world, art could be commercial, streetwear could be high fashion, and a civil engineer-turned-DJ could be a world-renowned creative.

Read More: 15 Times Designers Trolled the Fashion World With Ridiculously Expensive Designs

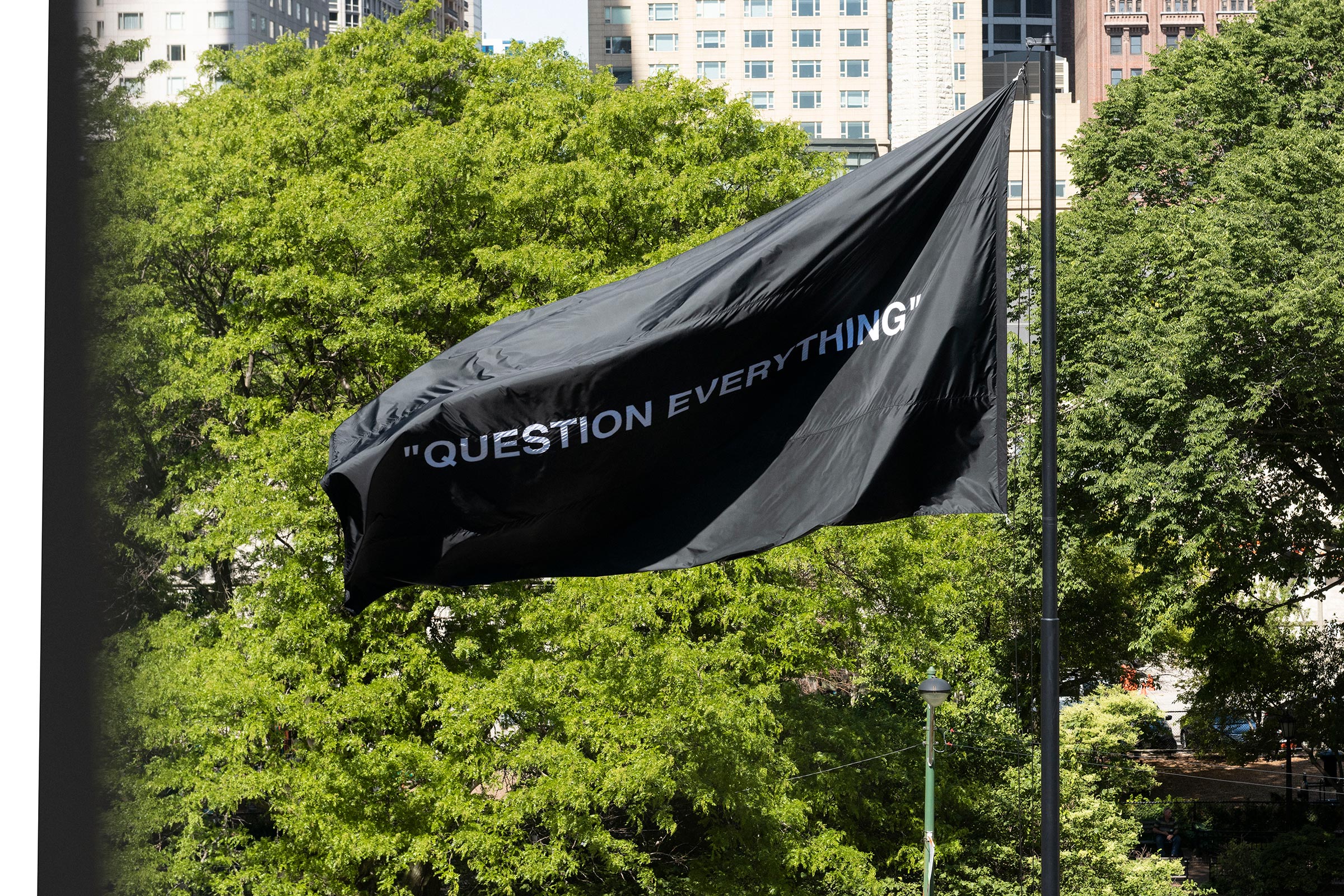

“Figures of Speech” exemplifies that breadth and sense of possibility. The show, which spans the first floor of the museum, features two decades of Abloh’s work, from high school architecture assignments and college sketchbooks to selections from his Off-White and Louis Vuitton fashion collections. Like Abloh, the exhibit defies convention, skipping standard wall hangings in favor of displaying colorful sneakers and visual collaborations with artists like Kanye West and Takashi Murakami on unfinished wooden tables designed by Abloh himself. To some, the exhibit may feel more like a studio or streetwear convention—a gift shop filled with Abloh-branded merch adds to this sense—but for curator Antwaun Sargent, breaking with tradition feels fitting for a show about Abloh.

“He was creating space for himself—but within those within creative spaces, he was creating space for other people,” Sargent says. “The fact that we’re having this exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, in an encyclopedic institution, is a testament to how boundaries were reshaped by Virgil in a way that allowed for Black creativity and concerns within spaces of architecture, fashion, and art to be fully recognized.”

While a prior version of the exhibit was shown in 2019 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Abloh’s hometown, the new show builds significantly on its predecessor, with additions like the imposing “Social Sculpture,” a large-scale wood cabin-esque gathering space in the center of the museum that Abloh and Sargent envisioned as a “museum within a museum.” “Social Sculpture” is meant to be a place for performances, DJ sets, lectures, community events, and other gatherings that might not typically be held in a museum. For Sargent, “Social Sculpture” speaks to Abloh’s spirit as a person who blazed a trail for a new type of artist, refreshingly free of institutional gatekeeping or pretension. Throughout his career, Abloh came to be known as much for his collaborations with emerging artists as for working with established people and brands, and was often lauded for his investment in young talent.

Read More: 5 Ways Virgil Abloh’s Influence Went Beyond the Sphere of Fashion

Though the exhibit is technically the first posthumous survey of Abloh’s work, Sargent insists that it is not a retrospective, because Abloh was an active collaborator on the curation and execution of the exhibit over a three-year period, even sending Sargent a checklist and notes just days before his passing.

“His legacy is still being made,” Sargent says. “Things are still coming out.” Another new addition to the exhibit is “Functional Art,” a huge chrome sound system that’s a reimagining of Braun’s iconic Wandanlage wall stereo. Abloh designed the piece in collaboration with the brand, but never got to see it materialize. Making its public debut, the stereo is mounted on the wall at the start of the exhibit, set to greet visitors with mixes of jazz and rap. It’s emblematic of Abloh’s appreciation for art that is not only beautiful but also useful, a value that was echoed in his collections with IKEA and the Swiss furniture company Vitra.

For Sargent, the exhibit is ultimately a testament to the ways in which Abloh continues to inspire and empower a new generation of creatives. “His legacy is one of example,” Sargent says. “His work gives a lot of people permission to do the work that they need to do.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Cady Lang at cady.lang@timemagazine.com