In some ways, the last place you’d want to put the James Webb Space Telescope is, well, in space. If you owned a $10 billion car, you wouldn’t leave it out in a hail storm, and while there’s no hail in space, there are plenty of micrometeoroids—high speed debris no bigger than a dust grain but moving so fast they can pack a true destructive wallop. Every day, millions of such fragments rain down on Earth, but they incinerate in the atmosphere long before they reach the ground. The Webb, parked in a spot in space 1.6 million km (1 million mi.) from Earth, has no such protection. And as NASA and others have reported in the past week, its mirror—the heart of the space telescope—has already been dinged five times by tiny space flecks, the most recent of which has done real, but correctable, damage.

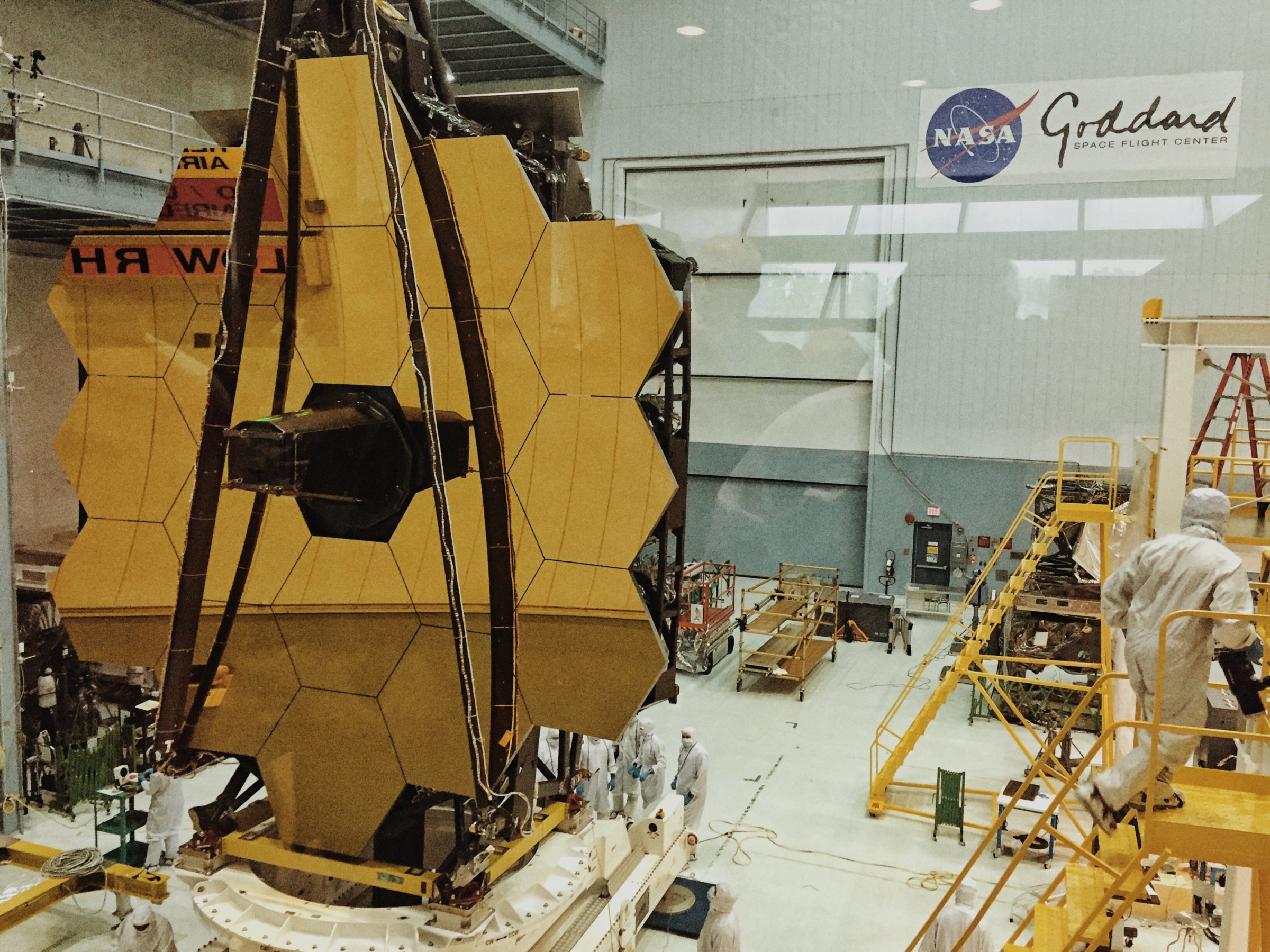

The Webb’s mirror is an exquisite piece of engineering. Measuring 6.5 m (21 ft., 4 in.) across, it’s made up of 18 hexagonal segments, each of which can be moved along seven different axes to allow controllers to focus the overall instrument. Together, the segments, made of beryllium, have an area of 25 sq. meters (269 sq. ft.). All of them are covered with reflective gold, but in a film so thin that if it were peeled off and tamped down into a sphere, it would measure no bigger than a golf ball. Meanwhile, the beryllium is so smoothly polished that if it were expanded to the size of the United States, its biggest imperfection would be 7.6 cm (3 in.). That’s a heck of a piece of hardware to leave exposed to the space elements. But if you’re going to do your work where Webb does, it’s a risk you have to take.

What makes the recent micrometeoroid hit especially troubling is that while NASA scientists simulated such collisions on the ground, the impact that occurred is bigger than the ones they modeled. “With Webb’s mirror exposed to space, we expected that occasional micrometeoroid impacts would gracefully degrade telescope performance over time,” Lee Feinberg, a Webb telescope optical manager, said in a statement. “This one…is larger than our degradation predictions assumed.”

That does not remotely mean that the telescope is seriously damaged before it can even go about its work. The position of the mirror segments can be moved in increments measured in nanometers—or billionths of a meter—allowing a damaged segment to be precisely refocused to cancel out the effect of the ding. Ground crews have already adjusted the damaged segment accordingly, keeping the telescope on track to release its first images to the public on July 12.

Webb does have ways to defend itself. NASA can often forecast the approach of micrometeoroid showers and the telescope can be moved to position its mirror away from the direction of the incoming debris. But there is no denying the certainty that over the decade or so the telescope is set to be operating it will be tattooed again and again by high speed dust and grains. There is no denying either, however, that in that same decade, the Webb should return magnificent science too. Space is a dangerous place to do business—but it’s a very rich one as well.

This story originally appeared in TIME Space, our weekly newsletter covering all things space. You can sign up here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com