When Jay Prakash, a 35-year-old shopkeeper, inherited his father’s local convenience store in Bengaluru, it had a dependable customer base streaming in from a wealthy apartment building known as the Diamond District. His 400 square-foot store sold rice, lentils, bread, snacks and fresh produce earning close to 15,000 rupees daily. But that was before the pandemic hit, and people started staying indoors. Now, he says, people are buying online through grocery services that promise extremely fast delivery times—20 minutes or less.

Prakash says his daily earnings have been slashed in half. “The old customers who knew about the quality of the product still buy from us, but it’s not the same.” For high school dropout Prakash, it didn’t seem possible to open an online store to compete. Designing a website, spending on marketing, and managing a delivery fleet felt incredibly daunting.

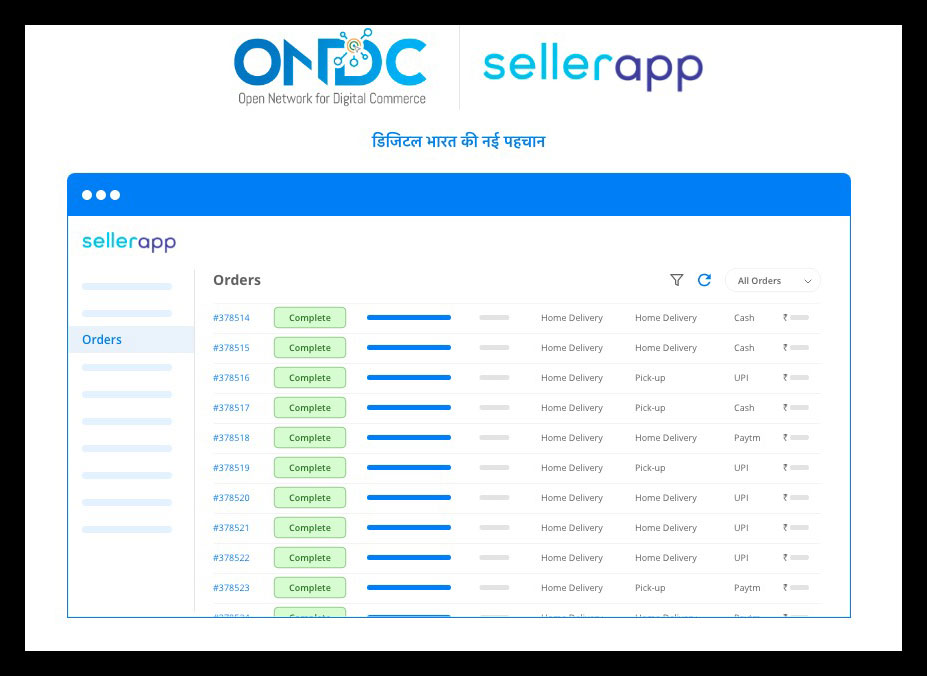

But a sweeping change over the last several weeks has rekindled hope for his two-decade old business, thanks to a new initiative from the Indian government. In a bid to create a level playing field for both online and offline players and reduce the dominance of American Big Tech, the Indian government is piloting its own solution that enables all kinds of sellers to display their products in shopping apps alongside bigger retailers. It’s called the Open Network for Digital Commerce, or ONDC. The system will allow offline retailers to compete with larger online retailers—including the many rapid grocery delivery services that have sprung up in the last year. Customers will be able to open their favorite shopping app (as long as it’s integrated with the ONDC) and find products from all sellers who are part of the ONDC. That would include nearby local neighborhood stores as well.

Pilots are underway for food and grocery, but the ONDC protocol will eventually be used for all kinds of commerce and services. According to reports, U.S. tech giants Amazon and Google are in talks to join the protocol, which would mean that when a customer opens the Amazon app, for example, they will be able to buy products from any seller registered with the ONDC.

An unusual solution to a fundamental problem

In a world that is being taken over by online players and Big Tech, this solution is unusual: a federal government creating a protocol to bring all kinds of sellers under one umbrella. Prior to this, the Indian government built a payment protocol—United Payments Interface—which allows real-time inter-bank transfer through smartphone apps, bringing online payment capability to everyone, including offline merchants. In May, nearly 6 billion UPI transactions were processed, showing the potential scale that could be achieved when the government builds tech tools for merchants. In fact, UPI is now being allowed to be used in countries outside of India as well.

“This [ONDC] is being done to address the fundamental problem of a platform-centric model leading to market concentration which is recognized world over,” said T. Koshy, chief executive officer of ONDC. “We have found a smart solution which is participatory, fair, inclusive and democratic.”

The government plans to link 30 million sellers and 10 million merchants to ONDC and expand this to 100 Indian cities by October. Industry experts say that online commerce has disrupted the industry and is expected to take some part of the traditional businesses, but it is also going to redefine the way people do business, with ONDC expected to play a significant role. “The creation of the ONDC is definitely going to redefine the whole segment,” said Kumar Rajagopalan, CEO of the Retailers Association of India. “Indians go online for the discovery phase of shopping, and if the customer’s trusted shop owner is online, then they will just switch over.”

Why small retailers needed help

The explosion of e-commerce has been brutal for Indian mom-and-pop retailers in the last decade with the proliferation of Amazon and Walmart-owned Flipkart. As internet penetration grew, Indians started using their smartphones for other services including ordering groceries. While this slowly chipped away at the businesses of local stores, it was the launch of the new category of instant grocery delivery—within 10 to 20 minutes— that further aggravated the situation. “These apps are giving discounts which we cannot afford,” said Uttam Kumar, a shopkeeper in Bangalore who saw his customer base dwindle from 800 to 200 a day. “I see that some of these apps have reduced the retail price and then given discounts on that as well.”

The instant grocery delivery market sprang up in India less than a year ago and is already at over $700 million, with estimates to grow almost 15 times its current size, to $5.5 billion by 2025. That would put it ahead of China and the EU in terms of adoption of these services, according to local research and consulting firm RedSeer. Ultra-fast online grocery delivery has taken hold in the U.S., and Europe, too, growing during the pandemic when many affluent people stayed indoors. Headquarters include Glovo in Spain, Gorillas in Germany, Cajoo in France, Zapp in London and Getir in Turkey.

In India, as in other countries, apps are causing side effects: more delivery workers on the streets (and at risk of accidents) and more small shop owners losing customers. But there is one thing that’s different in India: scale.

The unprecedented potential of online delivery

With an average age of 29 and the second-highest population in the world, India has one of the youngest populations—with high levels of disposable income and no time to shop because of high-pressure jobs. That, combined with the steady rise of the Indian middle class, has meant more Indians are using the growing number of online delivery services in the country.

One of these users is Keertana Rumalla, an architect from Hyderabad, for whom ordering groceries has become a daily affair. She orders on Swiggy’s Instamart—a rapid grocery delivery service—and buys only the limited supplies she needs to make that day’s lunch. And, a daily Toblerone bar. “I am so dependent on the app right now. I work from home and don’t have the time to go grocery shopping,” Rumalla, 31, told TIME, just as she excused herself from the call to fetch her groceries for that day as the doorbell rang. “I am definitely addicted to using this app.”

Many of these startups that users like Rumalla rely on are backed by venture-capital money from Western countries, including Accel Partners-backed Swiggy Instamart, Y Combinator-backed Zepto, Google-backed Dunzo and SoftBank-backed Blinkit. India has around 10 such services. Together these companies have carved out over $1 billion towards instant grocery delivery.

But the ONDC protocol can help tip the scale in the favor of offline sellers, who will now have a platform to compete with deep-pocketed startups. Koshy says that ONDC will help a seller succeed on the basis of what they can offer and the specialization they have, rather than the scale that venture capital money helps many achieve.

On May 14, Prakash fulfilled his first order through ONDC: instant noodles and coffee. Since then he has only received four other orders via the portal. But, he’s optimistic about the impending change, remembering the benefits of the government payment system, UPI. “When the government introduced UPI, I slowly understood the benefits of using that service,” Prakash says. “With ONDC, I am hopeful that it will bring my business back to how it used to be before the pandemic.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com